What Does Speed-Dating Research Say About Mate Selection?

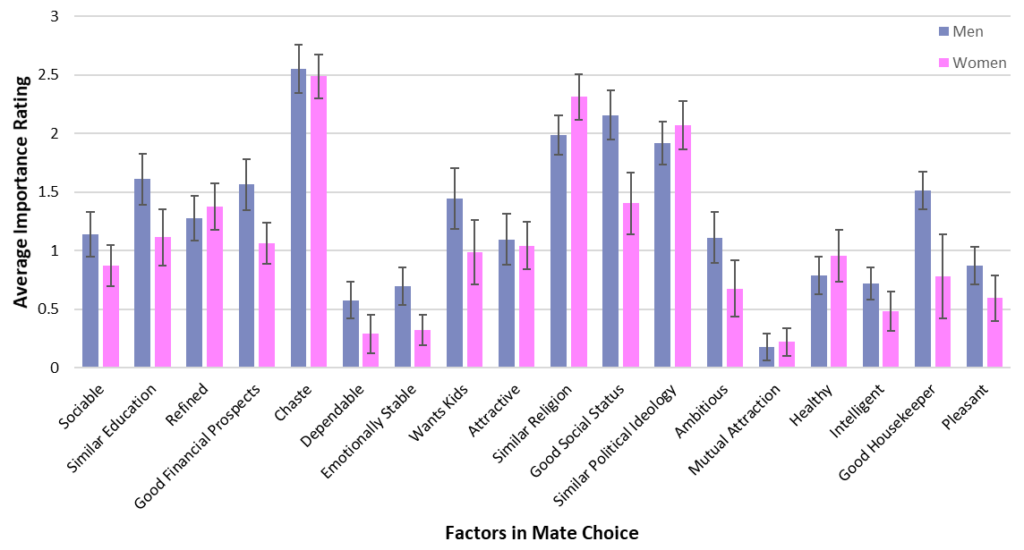

Research on mate preferences consistently reveals that men tend to place more value on physical attractiveness in a potential partner than women do, while women place more on cues to resource acquisition (Buss, 1989).

The evolutionary logic being that women’s physical attractiveness, being closely associated with youthfulness, in turn signals fertility and reproductive value. As men have historically played the role of providers, it goes without saying that characteristics such as earning potential, status, and traits such as ambition should play a larger role in their mate value.

The question naturally arises however, how well do these self-reported preferences map onto actual mate selection? As the manosphere is fond of reminding us: “look at what they do, not what they say”. It could be the case that people adjust their responses to fit certain societal expectations, or simply aren’t reliable judges of their own internal desires.

This where speed-dating experiments come in.

In a typical speed-dating event, daters will interact with a potential partner for about 3-5 minutes, with new partners rotating in and out until 10-20 have been completed. Participants then have the option of ‘yessing’ their partners. If two participants are a mutual yes, a they have the option to arrange a further date.

If the characteristics of speed-daters are assessed and then measured up against their popularity among the opposite-sex, we can presumably determine how well these a priori stated preferences correspond to real-life choices.

For instance, is it the case as conventional evolutionary psychology wisdom would have it that physical attractiveness predicts women being chosen more than it does for men, and vice versa for various non-physical characteristics?

Or is it the case as the black pill would have it that if anything women are more selective on the basis of physical attractiveness, concentrating on a small minority of ‘chads’, and other traits have little to no effect?

Does the so-called ’80/20 rule’ play out in an environment where the gender ratio is equal rather than highly skewed like online dating?

These are the premises which will be investigated in this research review in which I attempt to summarize the most relevant findings.

Studies

Kurzban & Weeden (2005): HurryDate: Mate preferences in action

This study examined results from 10,526 participants (2,650 when it came to those who reported their attractiveness) with a mean age of 31.4 for women and 33.8 for men, who engaged in a series of 3 minute interactions with roughly 25 opposite-sex participants.

It’s important to note that the physical attractiveness was self-rated here, as self-perceived attractiveness has shown to only be weakly associated with objectively rated attractiveness (a meta-analysis by Feingold in 1988 found a .24 correlation). The same was true of personality.

As expected, women practiced a higher degree of selectivity than did men. While men were chosen by 34% of women, women were chosen by 49% of men.

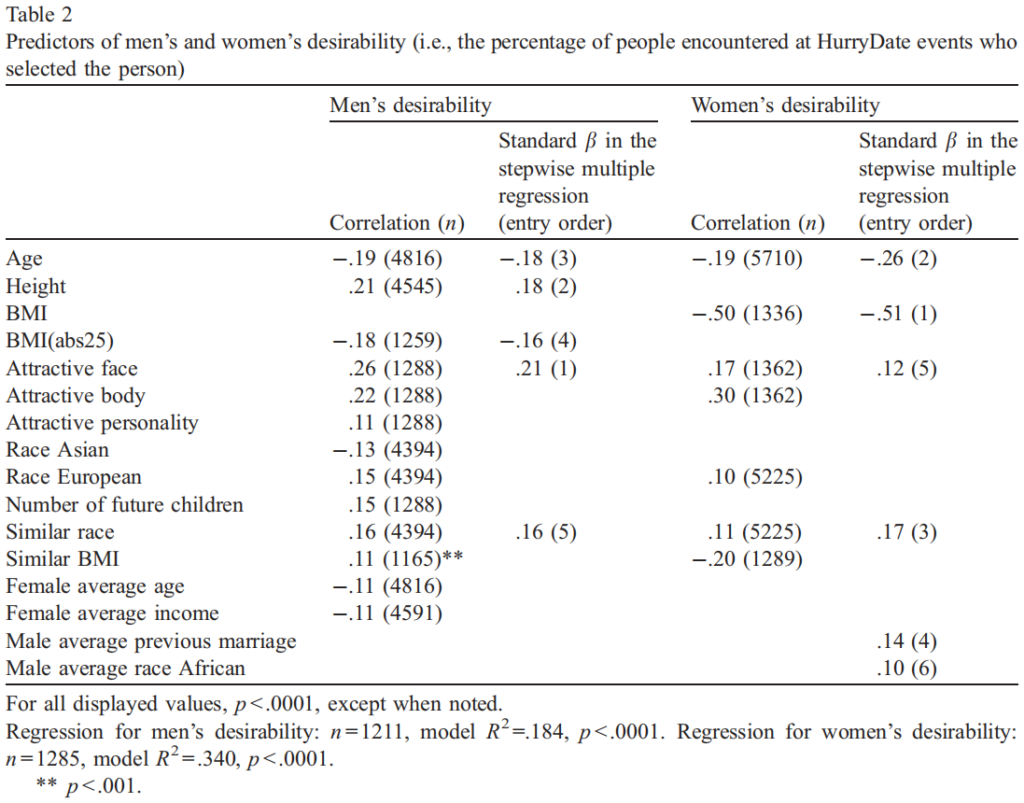

Here we see what predicted men and women’s desirability:

After controlling for other factors in a multiple regression analysis, the following factors emerged as significant predictors of men’s tendency to be chosen by their partners: Age (-.18), Height (.18), BMI(-.16, abs25 – i.e. close to the median), Self-Rated Facial Attractiveness (.21), and Similar Race (.16 – indicating assortative mating for race).

For women, it was: Age (-.26), BMI (-.51), Self-Rated Facial Attractiveness (.12), Similar Race (.17), and men having divorced or being black (these emerged after controlling for BMI).

So overall, the only predictor which had a moderate to strong relationship with being chosen was women’s BMI, with thinner women being much preferred. This explained 25% of the variance, with other factors explaining an additional 9%. Only 18% of the variance was explained for men.

Desirability was correlated with selectivity for both men (.21) and women (.18), meaning those who were yessed more gave less yesses out themselves.

These are the traits which predicted selectivity:

For men, having a BMI close to 23, a higher income, less children, and facing women with higher average BMIs predicted their selectivity.

For women, having a lower BMIs and facing men with a higher average age did.

They also found some evidence for assortative mating for height.

Overall, quite underwhelming results. Some traits like education, income, religion, sociosexuality didn’t even show up on the first table shown as none of the correlations reached 0.1.

Physical traits overall predicted women’s desirability to a greater extent (about 27% vs. 10% for men) but maybe that would change to a degree if we included other metrics such as shoulder to waist ratio for instance, and again objectively or partner rated attractiveness may be more effective.

On the other hand nothing else really had any effect. While income predicted men’s selectivity, it had no effect on their desirability. Was the information not conveyed adequately perhaps?

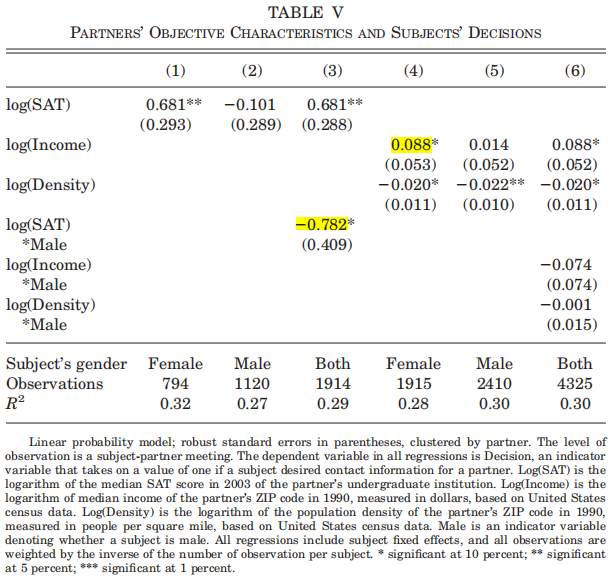

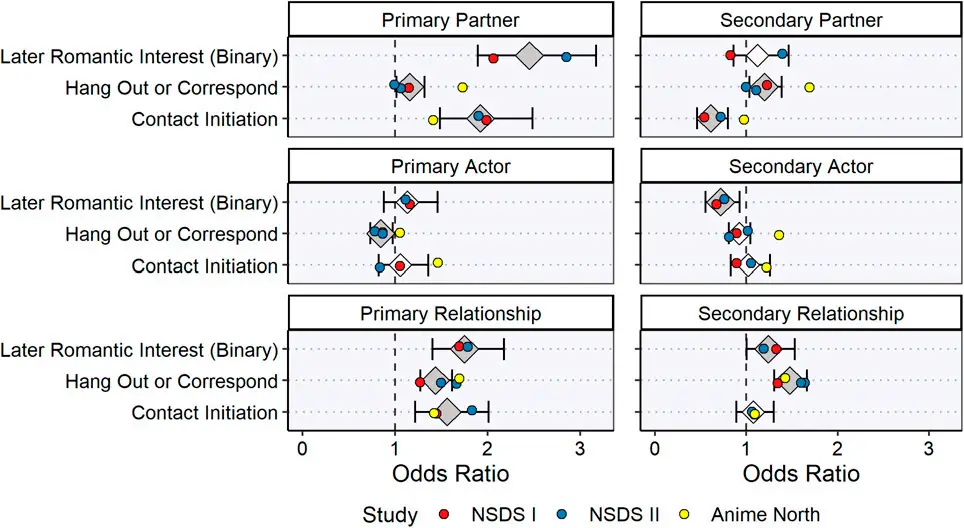

Fisman et al. (2006): Gender Differences in Mate Selection: Evidence From a Speed Dating Experiment

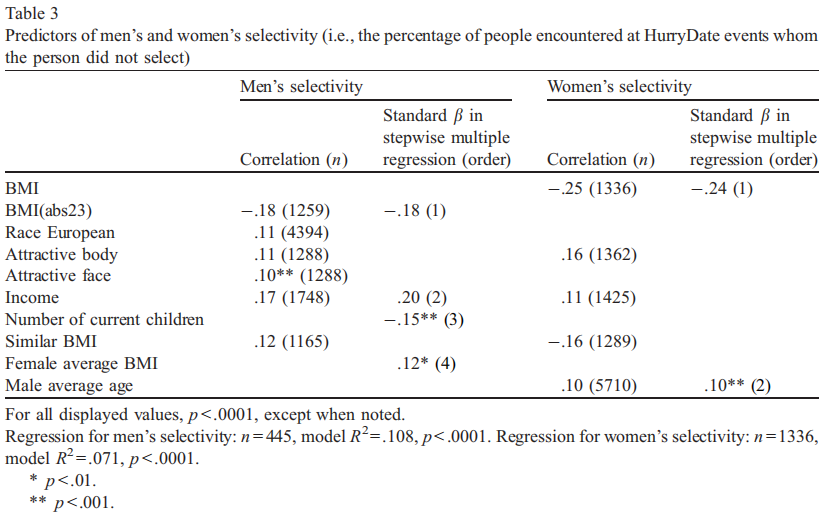

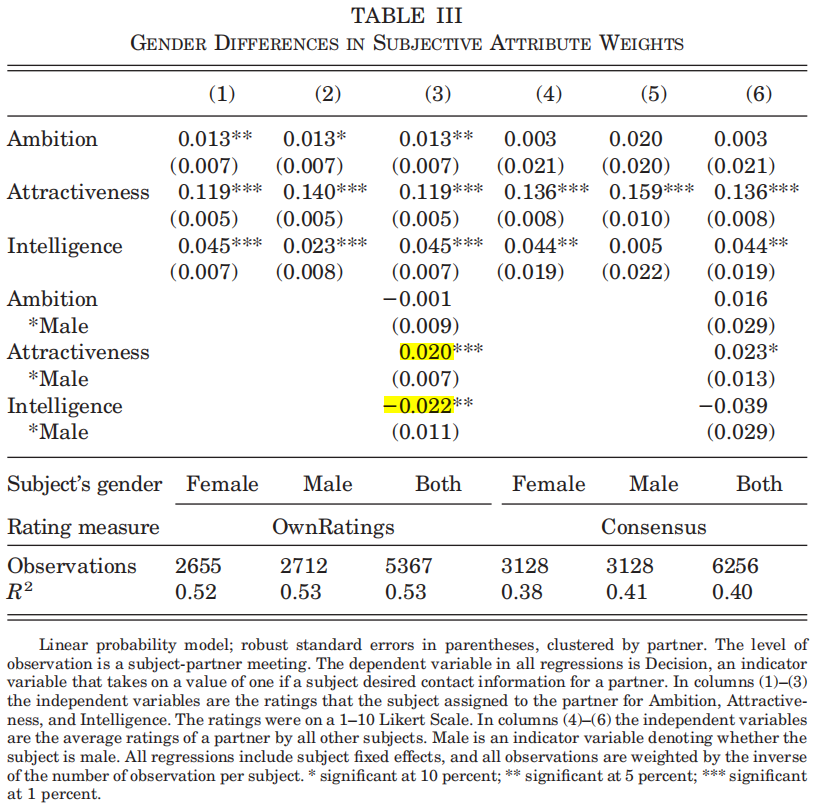

About 400 undergrads met between 9 and 21 potential mates for 4 minutes each. The traits in this study were rated by the speed-dater’s partners.

The effect of physical attractiveness was higher on women’s desirability, with each point of physical attractiveness raising their likelihood of being yessed by 14%, relative to 11.9% for men. This difference was significant at the .01 level.

The effect of perceived intelligence however was higher on men’s desirability, with each point raising their likelihood of being yessed by 4.5%, relative to 2.3% for women.

Sincere, fun, and shared interests were left out as they weren’t as relevant to the evolutionary psychology question and they failed to find gender differences.

They also found that ambition and intelligence above a man’s own level put him off selecting the partner.

In terms of objectively measured traits, more desirable men had higher SAT scores (significant difference at the .1 level), and the effect of income was significant for them at .1, but the difference wasn’t.

Another interesting finding was that women’s selectivity rose with group size, men’s didn’t. In smaller sessions with less than 15 partners, men and women’s selectivity was almost identical with participants of both genders yessing about half of their partners. In larger sessions, women’s yessing rate dropped to a bit over a third.

They note however an important caveat to the results of the study, what they call a possible ‘articulation effect’ whereby women may have felt a stronger desire than men to feel like they were placing value on non-physical traits when making their decisions (they made them at the same time).

Todd et al. (2007): Different cognitive processes underlie human mate choices and mate preferences

Subjects: 20 women with a mean age of 34 and 26 men with a mean age of 35.6. People’s stated preferences were close to their own self-perceived trait values. Women were more selective, yessing an average of 4 times compared to 7.35 for men.

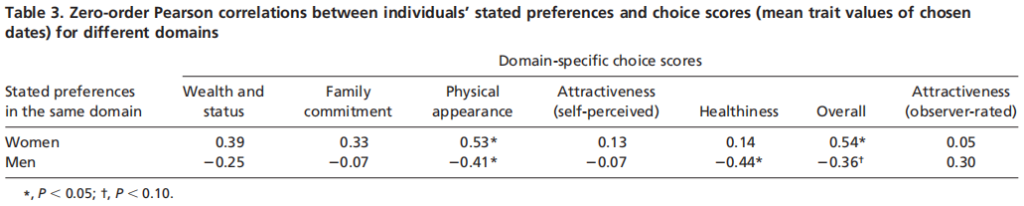

Below we see to what degree stated preference lines up with their choices:

Not terribly well. The only positive correlation reaching significance was for women and their stated physical appearance preferences.

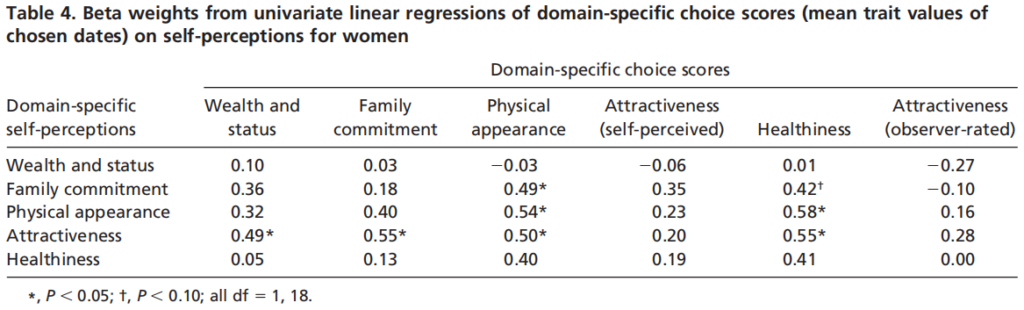

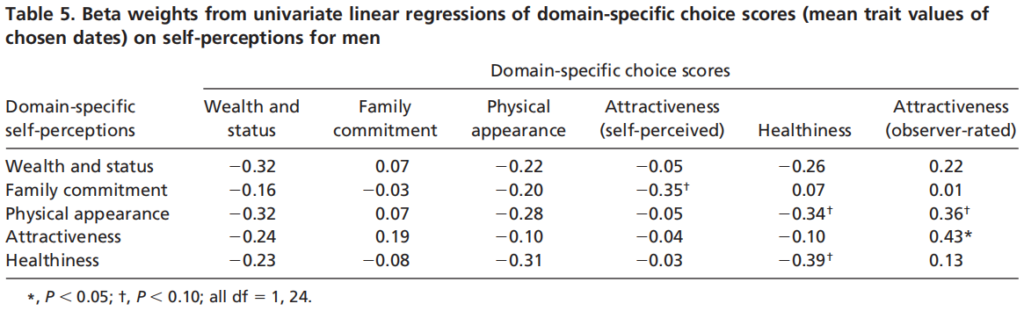

When it came to self-perceived mate value, self-perceived attractiveness predicted the self-perceived mate value of men she chose on all traits except men’s attractiveness. There were no associations for men except for their self-perceived attractiveness and women’s objectively rated attractiveness.

Women’s self-perceived attractiveness was the only domain-specific self-perception that was significantly correlated with receiving yesses (.43). Externally rated attractiveness correlated higher at .86. According to Eastwick et al. (2014), the correlations for men were .33 and .49 respectively. The difference in objectively rated attractiveness’ predictive power was thus large and statistically significant at .05.

Since women’s self-perceived attractiveness wasn’t related to the number of men to whom they made offers, they concluded that “Thus, the women seemed to be using an effective strategy for adjusting their threshold for making offers to a small number of men of similar desirability as a mate, trading off their physical attractiveness against the overall quality of men across different domains, to achieve a few good matches”.

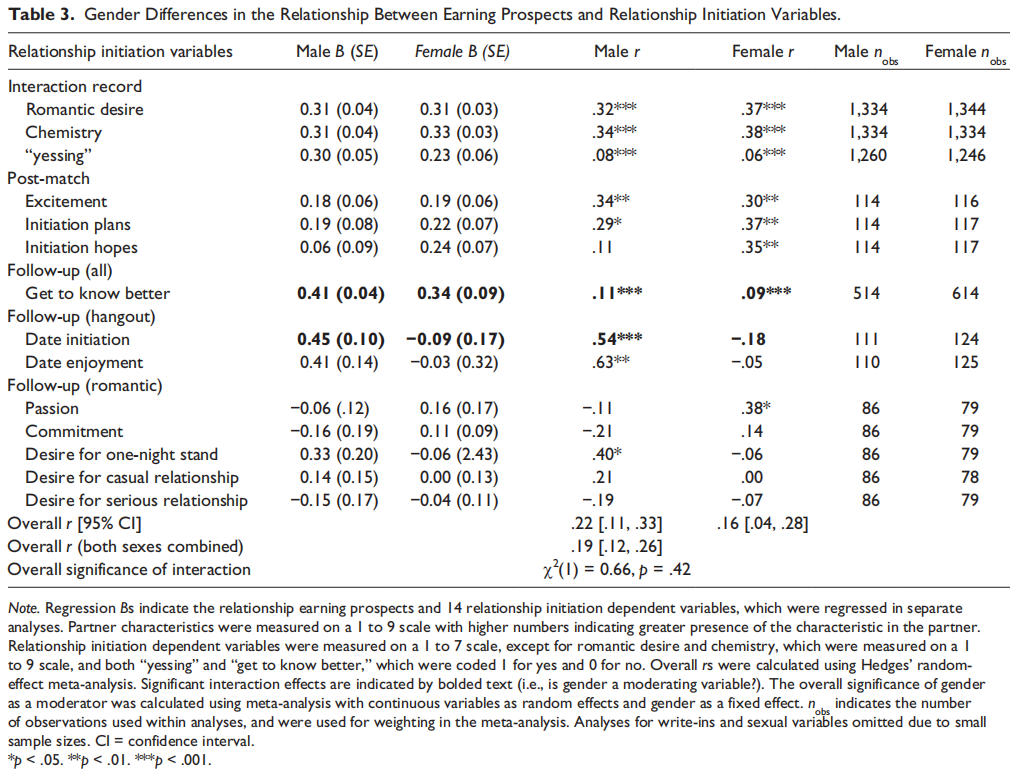

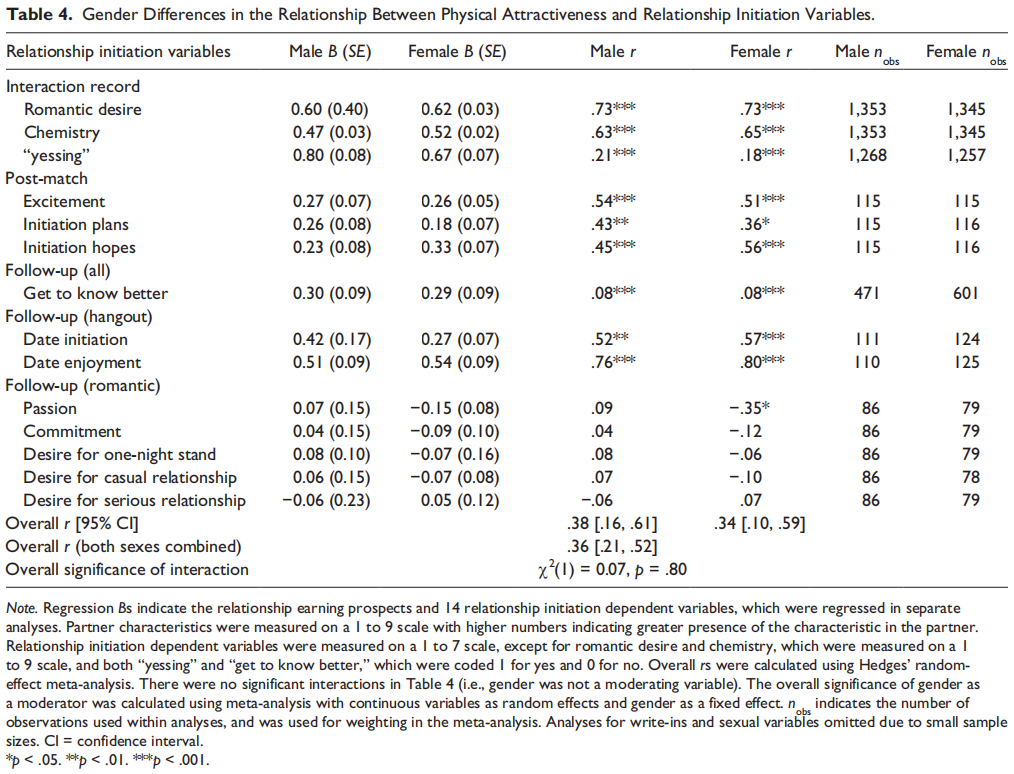

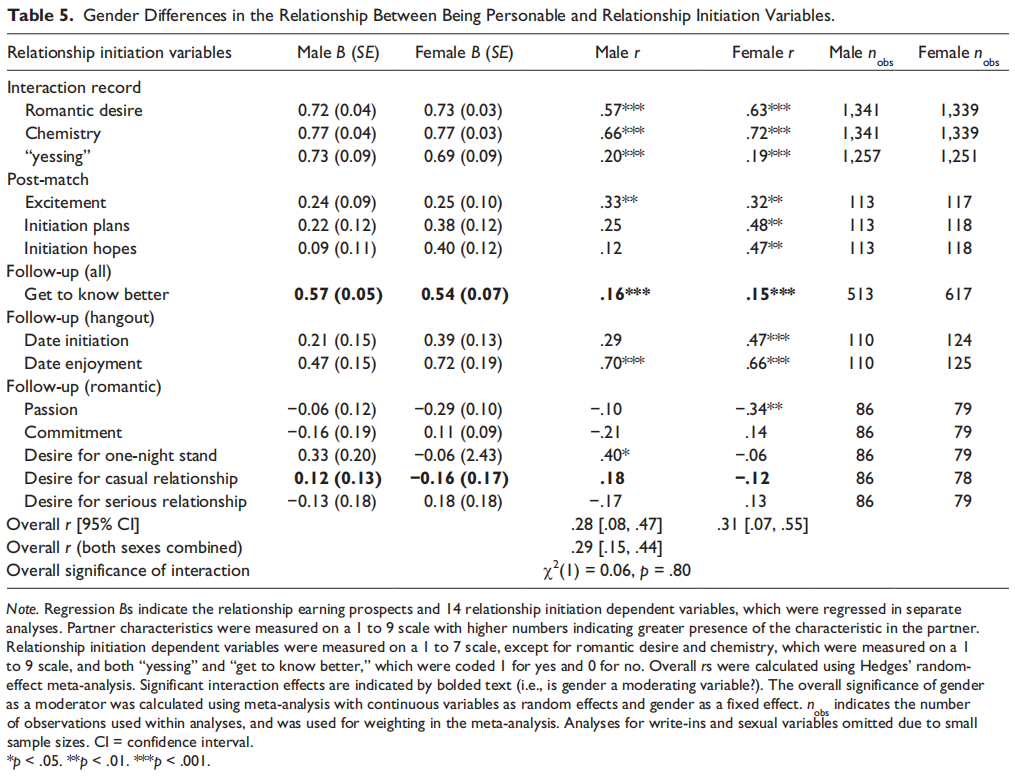

Eastwick & Finkel (2008): Sex Differences in Mate Preferences Revisited: Do People Know What They Initially Desire in a Romantic Partner?

82 male and 81 female undergrads with a mean age of 19.6 engaged in 4 minute dates with 9 to 13 opposite-sex participants.

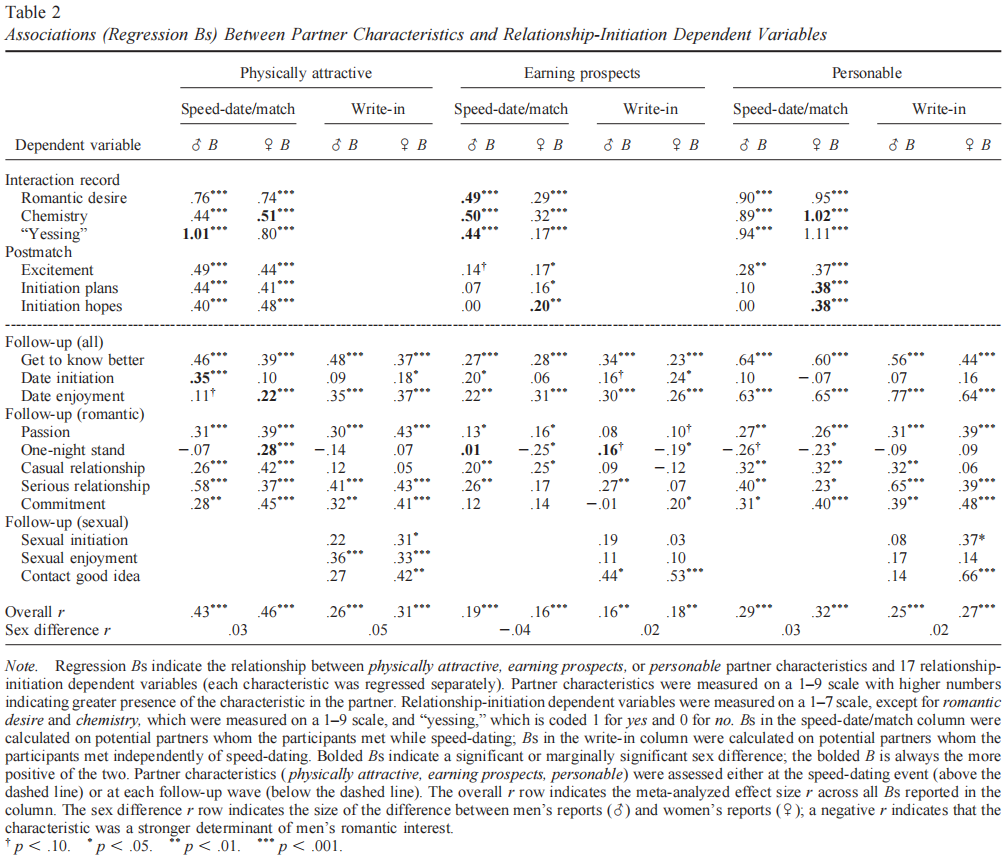

When it came to stated mate preferences, the typical pattern emerged wherein men more than women reported that physical attractiveness was important in an ideal romantic partner and would matter more in their speed-date decisions, and women stated that earning prospects would matter more. No difference was found when it came to personable characteristics however.

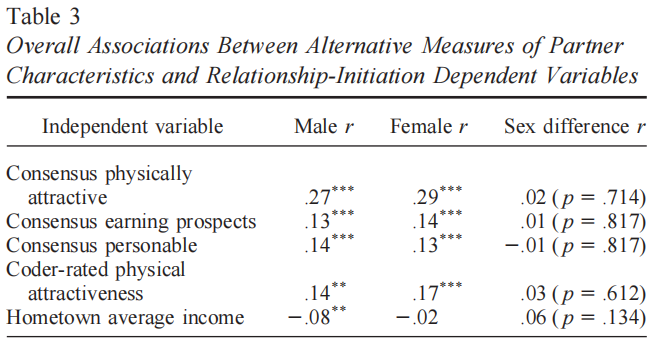

The question is of course, did these manifest in actual partner choices? Here’s how these traits predicted relationship-initiation variables:

We see that while as was the case in Fisman et al. physical attractiveness was a greater predictor of men yessing their partners than vice versa, when these other variables such as chemistry and date enjoyment were added into the analysis there wasn’t a significant difference in the aggregated effect size.

The same held true for earning prospects and personability.

They also asked to provide details about anyone outside of their speed-dates or matches who they had romantic interest in over the course of the month, and no differences emerged there either.

To determine whether this absence of a sex difference wasn’t caused by the subjectivity of ratings, they also applied the same meta-analytic process to averaged ratings from speed-daters, attractiveness ratings by independent judges, and the average income from the participants’ hometowns.

The absence of sex differences remained. The effect sizes also seem to have diminished, especially in the case of externally rated attractiveness.

They also failed to detect any similarity effects. In other words, participants responded more positively to their dates who scored higher on each characteristic regardless of their own score.

A possible criticism is that these differences in preferences are most pronounced in the context of long-term relationships, which this undergrad sample may not be highly oriented towards, but they didn’t find good evidence for sex differences in predictors among those with a stronger desire for a serious romantic relationship either.

A possible explanation suggested for the lack of sex differences in selection based on earnings potential is that they are relevant mostly insofar as a certain threshold is necessary to pass, which the men in the current sample may have passed.

So overall we find more evidence that declared preferences may have limited relation to observed preferences. It may be argued that the actual decision to accept or reject a match (yesses) should take precedence over the other variables which may represent less tangible feelings, but at the same time that’d mean we’d have to accept that men also care more about their partner’s earning prospects.

Houser et al. (2008): Dating in the fast lane: How communication predicts speed-dating success

This study was based on data from the same sample as the previous Houser et al. study, but looked at ‘interpersonal attraction’, which combined physical and social attraction, ‘nonverbal immediacy’, which is ‘a perception of closeness and liking created through communication. That is, behaviors such as eye contact, physical closeness, smiling, head nods, body relaxation, and vocal variety foster a perception of closeness that signals interest, simulates interaction, enhances relational development, and raises self-esteem’, and then homophily, or sameness.

They judged their partners in these characteristics using various measures following their dates.

POV, or predicted outcome value judgements, correlated significantly with interpersonal attraction (.59), nonverbal immediacy (.45), and homophily (.35).

After conducting a multiple regression analysis however, the effect of interpersonal attraction remained significant (β = .45), as did nonverbal immediacy (β = .21), but homophily didn’t.

They then looked at how these variables predicted actual date outcomes by sex.

The odds ratios indicated that for men the odds of estimating who will opt for a date improved by 11% for each unit increase of homophily, 10% for nonverbal immediacy behaviors communicated, and 7% for interpersonal attraction.

For women, the percentage for nonverbal behaviors was 12% and for interpersonal attraction was 5%, but no effect of homophily was detected.

They say that nonverbal immediacy behaviors being the strongest predictor of date decisions for women is consistent with past research indicating they’re more cognizant of nonverbal behaviours.

Luo & Zhang (2009): What Leads to Romantic Attraction: Similarity, Reciprocity, Security, or Beauty? Evidence From a Speed-Dating Study

54 male and 54 female college students with an average age of 19.5 engaged in 5 minute interactions with between 14-20 participants. Attractiveness was rated by independent judges, and all the other variables were self-rated.

When it came to variables predicting attraction, men’s physical attractiveness and sport activity predicted women’s attraction, while women’s age, weight (negatively), physical attractiveness, sport activity, political attitude, neuroticism (negatively), extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, negative affect (negatively), anxiety (negatively), and self esteem predicted men’s attraction. Age, neuroticism, extraversion, negative affect, and avoidance showed significant sex differences.

These are probably the most anomalous results of all the studies. It’s possible these other variables were more highly correlated with physical attractiveness for women in this sample. Even physical attractiveness’ effect was far above that seen in any other study, and this was objective ratings which tends to show lower correlations than partner ratings. No effects of similarity were found either.

Lenton & Francesconi (2010): How Humans Cognitively Manage an Abundance of Mate Options

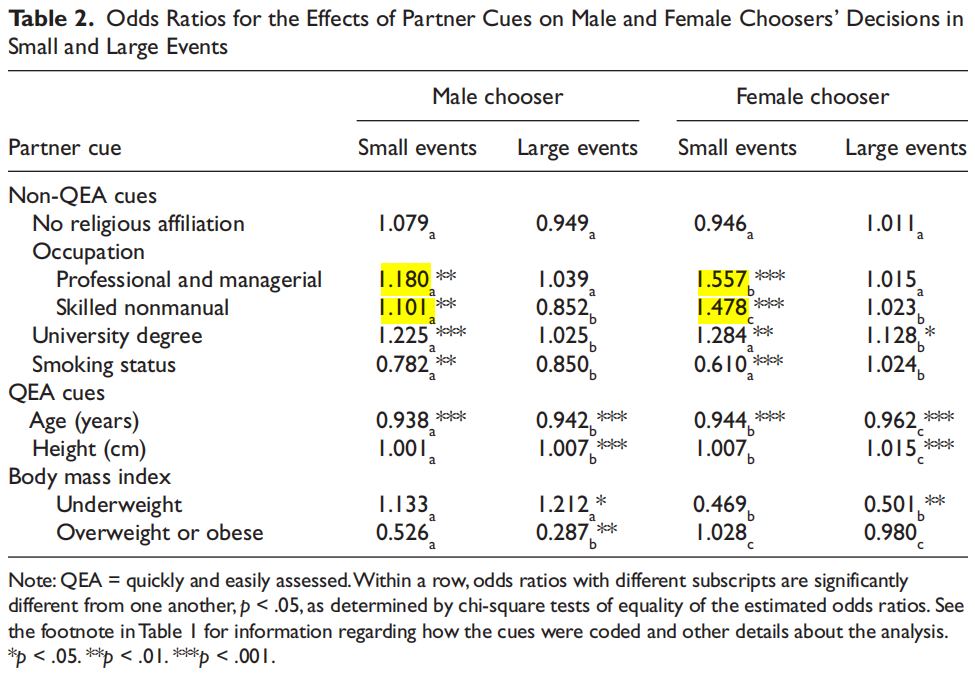

This study analyzed data from 1,868 women and 1,870 men engaged in 3 minute dates over 84 speed-dating events which gathered an average of 23.6 male and 23.5 female participants each.

Events were categorized as ‘small’ if they presented participants with between 15-23 partners, and ‘large’ between 24-31.

Almost every cue was qualified by event size, and in some cases gender moderated this effect.

Professional and managerial and skilled nonmanual occupations predicted men and women’s desirability only in small events, with them improving men’s desirability to a greater extent.

Height influenced decisions only in large events, with both men and women choosing taller partners, though women to a larger extent.

Being overweight didn’t affect men’s desirability one way or the other, but had a negative effect for women in large events while the effect wasn’t statistically significant for small ones.

The effect of being underweight was also only significant in large events, with it being a disadvantage for men but an advantage for women.

Overall, QEA (‘quickly and easily assessed’) cues played a larger role in the large sessions, which implies that when there is an abundance of options, people focus more on easily assessed traits.

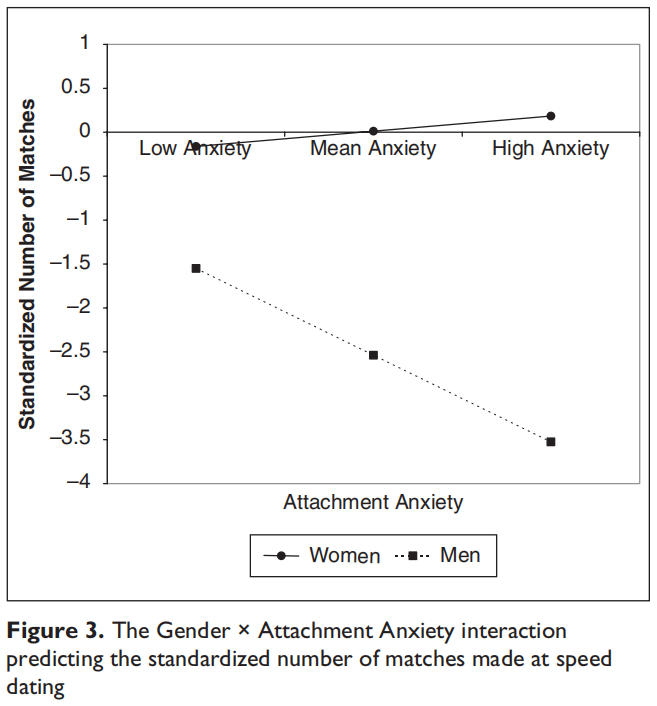

McClure et al. (2010): A Signal Detection Analysis of Chronic Attachment Anxiety at Speed Dating: Being Unpopular Is Only the First Part of the Problem

38 men and 35 women with a mean age of 21.2 engaged in 3 minute interactions with between 16-23 partners.

Participants filled out the Experiences in Close Relationships Inventory which contains 18 items measuring anxiety and 18 measuring avoidance.

Women, more attractive people, and less anxious people were more selective.

While there was not a significant association between attachment anxiety and attractiveness, the former also negatively predicted popularity.

When it came to matches however, only more anxious men suffered:

For women the effect was likely offset by their reduced selectivity, while anxious men’s reduced selectivity didn’t provide them the same benefits.

There was no gender difference reported in the effect of attractiveness, and looking at Eastwick et al. (2014) which got access to unpublished data, this is likely because there wasn’t one. Self-rated attractiveness appears not to have been significantly associated with popularity, while objectively-rated attractiveness (.32) had much less effect than partner-rated attractiveness (.64), which implies that partner-rated attractiveness may be conflated with the effects of non-physical characteristics.

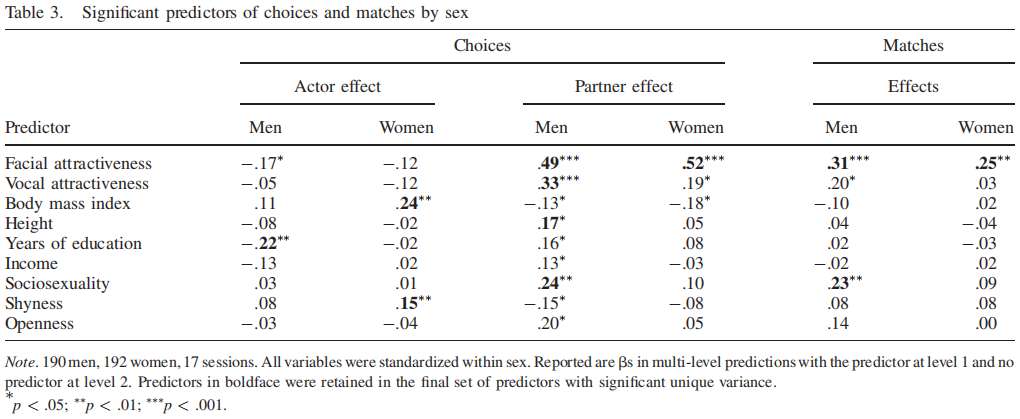

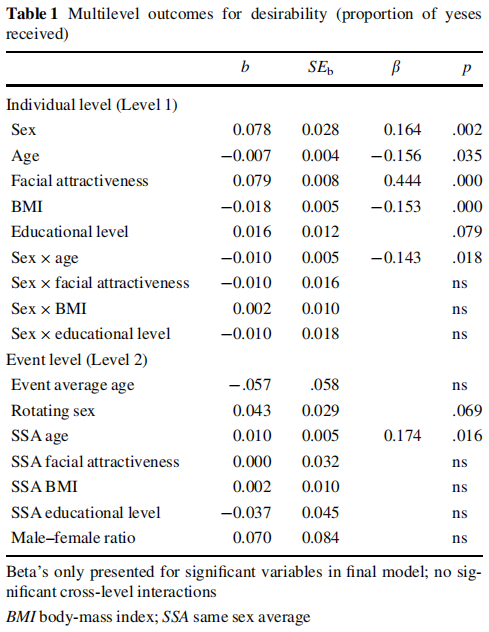

Asendorpf et al. (2011): From Dating to Mating and Relating: Predictors of Initial and Long-Term Outcomes of Speed-Dating in a Community Sample

190 men and 192 women with a mean age of 32.8 engaged in engaged in 3 minute interactions in 17 sessions including 17-27 participants.

Participants were rated for facial and vocal attractiveness by opposite-sex independent judges, and filled out a questionnaire regarding a number of other variables.

116 men and 116 women received at least one match. While the chance of being chosen by a dating partner was 34.7%, the chance of a match was 11.5%. The rate was slightly higher for women, 37%, than men, 32%.

They also found a small but significant dyadic effect whereby people’s preferences for certain partners tended to be reciprocated after controlling for choosiness and popularity.

There was a 38.6% chance of meeting each match the day after, rising to 81.1% for meeting any at all since the average match rate was 2.1. The overall rate including those who received no matches would be 49.2%. For having sexual intercourse within 6 weeks it was 4.3%, for developing a romantic relationship within 6 weeks it was 6.6%, for having sexual intercourse within a year it was 5.8%, and for being in a romantic relationship a year after it was 4.4%.

Here are how various variables predicted choices:

The effect of facial attractiveness on being chosen was highly similar for men (.49) and women (.52).

We also see however that a broader ranger of criteria predicted men’s than women’s popularity.

While the only other variables predicting women’s popularity were vocal attractiveness and BMI, men’s was also predicted by height, years of education, income, sociosexuality, shyness, and openness.

Still, facial attractiveness remained the most significant individual predictor by a significant margin, and most of these effects didn’t survive a multiple regression analysis.

Eastwick et al. (2011): Implicit and Explicit Preferences for Physical Attractiveness in a Romantic Partner: A Double Dissociation in Predictive Validity

In study 4 of this study, 88 men and 86 women engaged in 4 minute interactions with between 11-12 other individuals.

Attractiveness was measured by a combination of the mean rating given by the people they dated and given by opposite-sex nonparticipants who rated their photo.

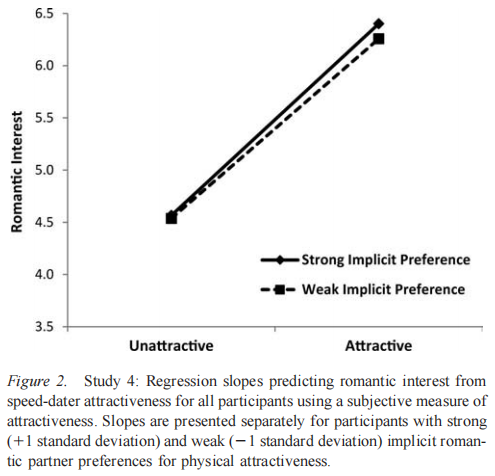

While men (7.72) indicated a greater preference for physical attractiveness than women (7.2), the ‘implicit preferences’ (how much participants reported being sexually attracted to their partners and their likelihood of saying yes to them) for physical attractiveness didn’t significantly differ between men (35.5) and women (25.6).

Explicit preferences didn’t interact with subjective attractiveness in predicting men or women’s romantic interest in their partners.

Implicit preferences did however, and the interaction wasn’t moderated by sex.

When it came to objective attractiveness ratings, explicit preferences still had no interaction effect.

Implicit preferences did once again, but this time only for men.

According to Eastwick et al. (2014), subjective attractiveness ratings predicted men’s interest at .49 and women’s at .4, while self-perceived ratings did at 0.07 and .11, and objective ratings at .26 and .2, so it may have had a marginally larger effect on men’s interest, but it’s hard to say.

Humbad (2012): Exploring mate preferences from an evolutionary perspective using a speed-dating design

207 male and 216 female undergrads engaged in 5 minute interactions in groups of 6-10 participants.

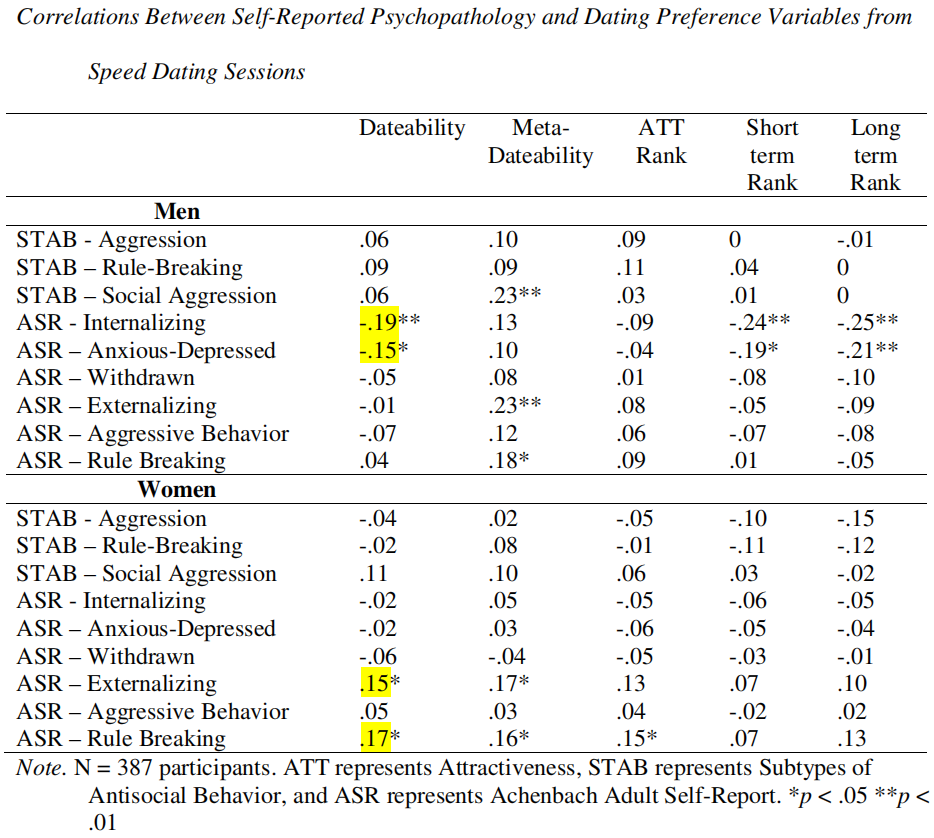

They filled out questionnaires relating to Big-Five personality traits, internalizing and externalizing psychopathology, and antisocial behavior.

Independent judges rated their attractiveness and how ‘warm’ or ‘dominant’ etc. they seemed. The participants were also asked to rate their partner’s attractiveness.

Men and women tended to agree on the extent to which participants of the opposite-sex were dateable.

When it came to self-perceptions however, men who believed that others perceived them as dateable weren’t rated as more dateable, while women who did were.

There wasn’t much distinction between the various items on the dating preferences questionnaire, implying that it’s difficult for individuals to differentiate between long- and short-term romantic interests in a 5 minute interaction (or maybe there isn’t much distinction in reality).

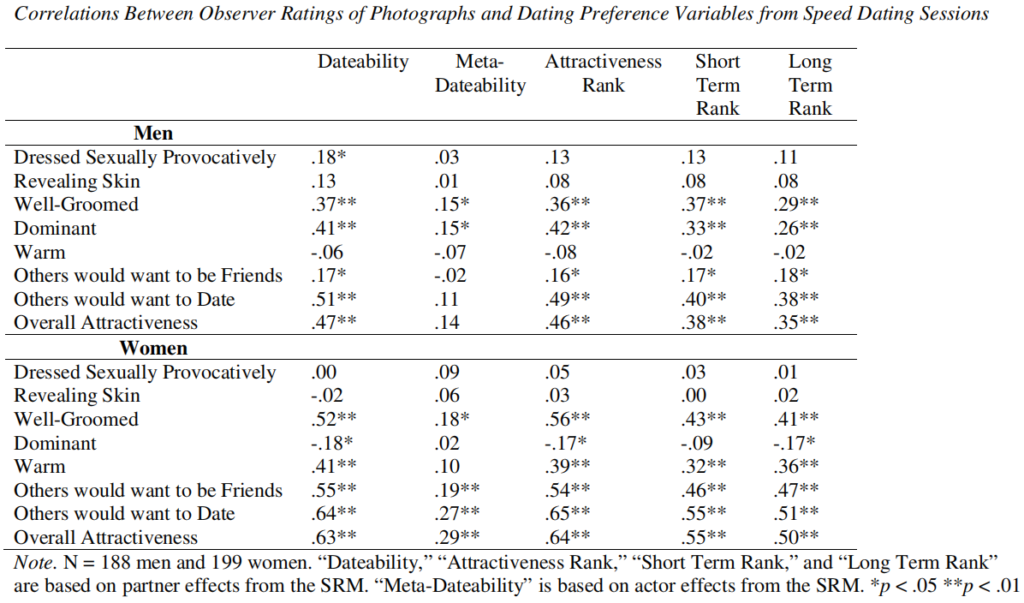

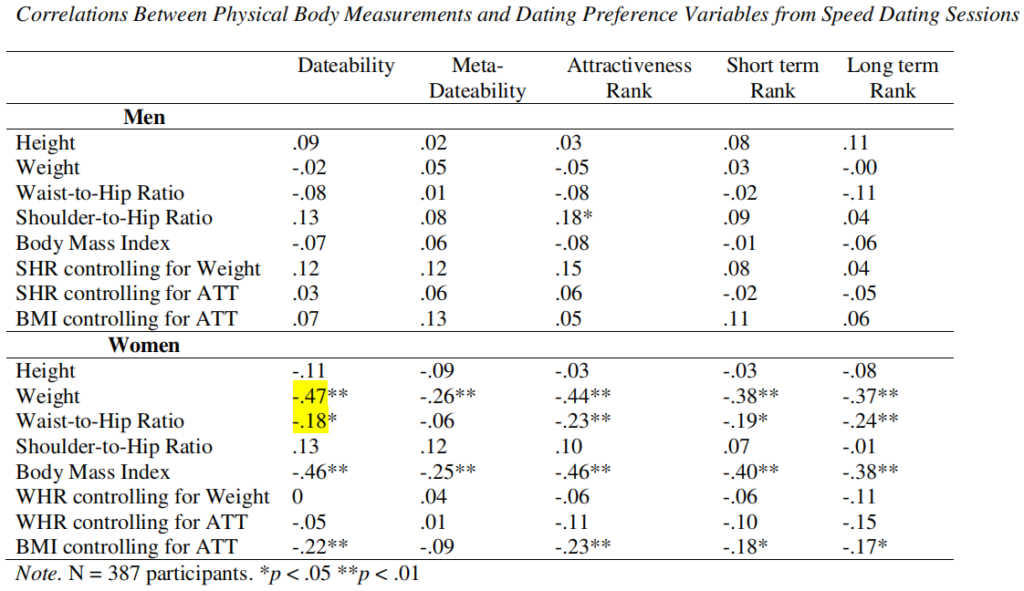

Here are the correlations between objectively-rated appearance variables and dating preference variables:

Overall attractiveness correlated at .47 with men’s dateability, .38 for their short-term rank, and .35 for their long-term rank. It correlated at .63 for women’s dateability, .55 for their short-term rank, and .5 with their long-term rank. These differences would likely be statistically significant considering .14 correlations were at the .05 level.

Being well-groomed also correlated quite highly with dateability, and while being rated as more dominant correlated with men’s dateability, being rated as more warm correlated with women’s. All these variables were quite strongly associated with attractiveness however.

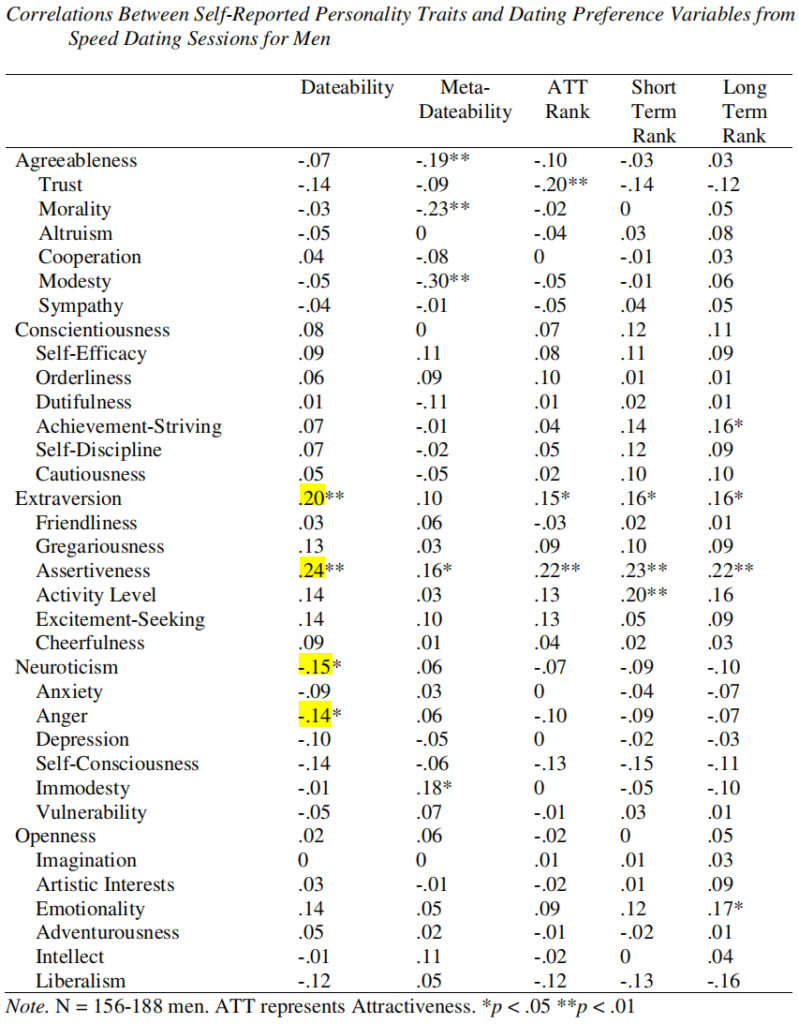

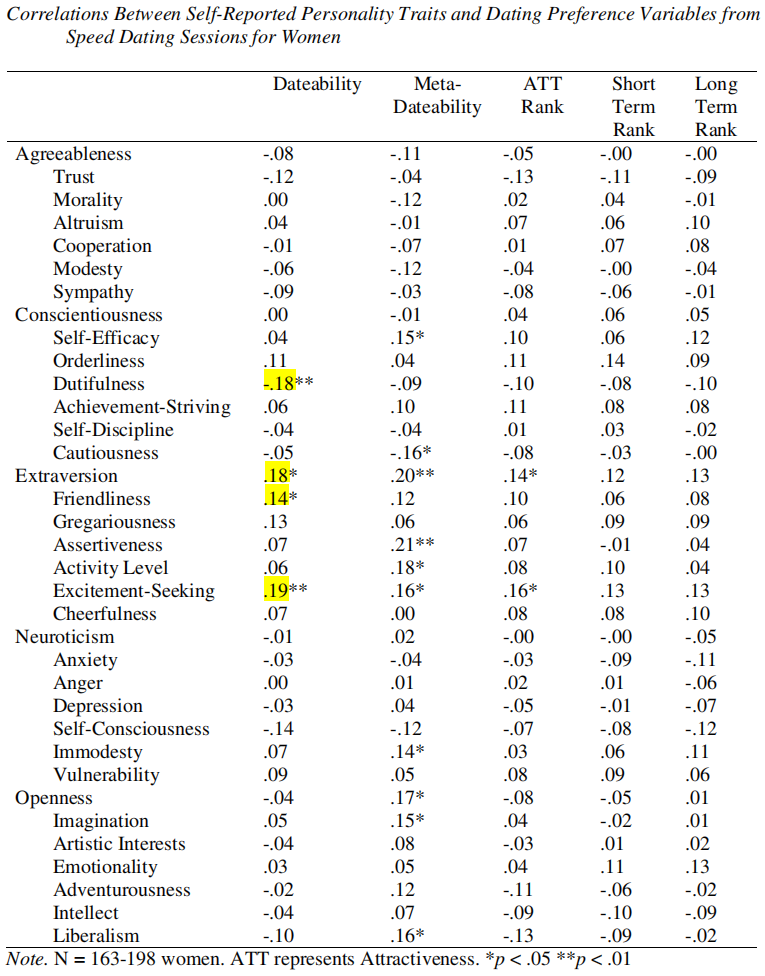

Several Big 5 personality traits also had an effect:

For men, extraversion correlated with dateability at .2, with the strongest effect being in the assertiveness component (.24, remaining significant after controlling for attractiveness). Neuroticism also correlated negatively at -.14.

For women, extraversion correlated at .18, and the dutifulness component of conscientiousness correlated at -.18.

Internalizing behaviours (mostly anxiety/depression) negatively affected men’s dateability, while externalizing behaviours (the rule breaking scale) positively predicted women’s:

The effect of the rule breaking scale was no longer significant after controlling for the alcohol component, and this component also became non-significant after controlling for attractiveness.

The effect of men’s anxiety and depression remained significant after controlling for attractiveness however.

Finally, body measurements:

Weight was ‘heavily’ associated with women’s dateability in the expected direction, and lower waist-to-hip ratio also had an effect.

No body measurements had any effect for men however. Height correlated at .09 but didn’t reach significance. Shoulder-to-hip ratio was almost significant, and correlated with attractiveness rank.

Shifts in the menstrual cycle didn’t affect dating preferences.

Li et al. (2013): Mate Preferences do Predict Attraction and Choices in the Early Mate Preferences do Predict Attraction and Choices in the Early Stages of Mate Selection

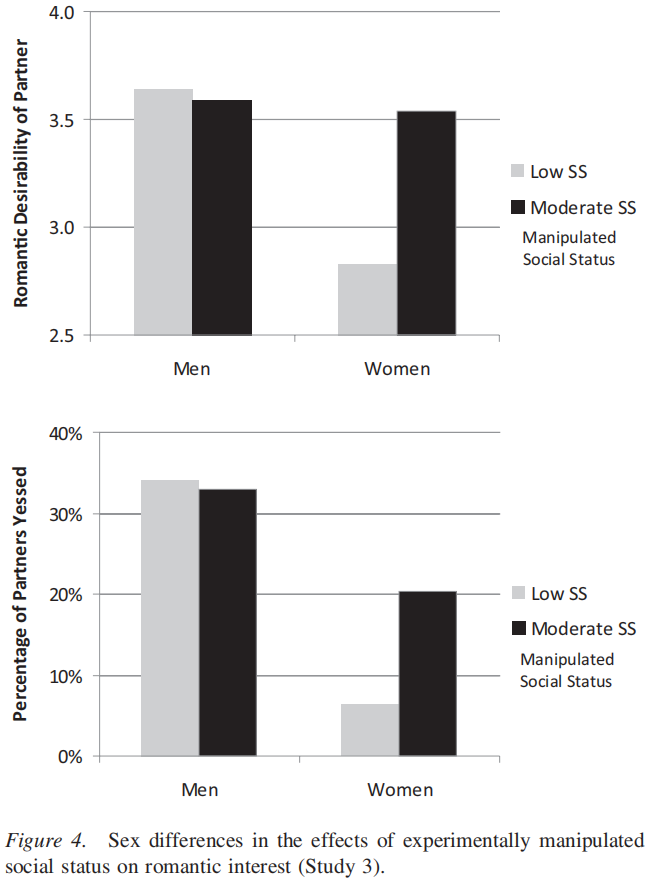

In study 3, 60 male undergrads with a mean age of 23 and 82 female undergrads with a mean age of 21.2 participated in 4 minute speed-dates with two individuals with low-status jobs and two other college students from a university of equal prestige.

Participants were asked the importance of physical attractiveness and earning prospects in a potential date, and rated their date partners on these traits, on romantic desirability, and whether they’d like to exchange contact information. As expected, men placed more value on physical attractiveness and women on earning prospects.

When it came to romantic desirability a significant sex interaction was found for manipulated social status, with women’s attraction increasing towards moderate rather than lower status, while men’s attraction was unmoved. This was also true for yessing.

There was a stated importance interaction effect for both romantic desirability and yessing.

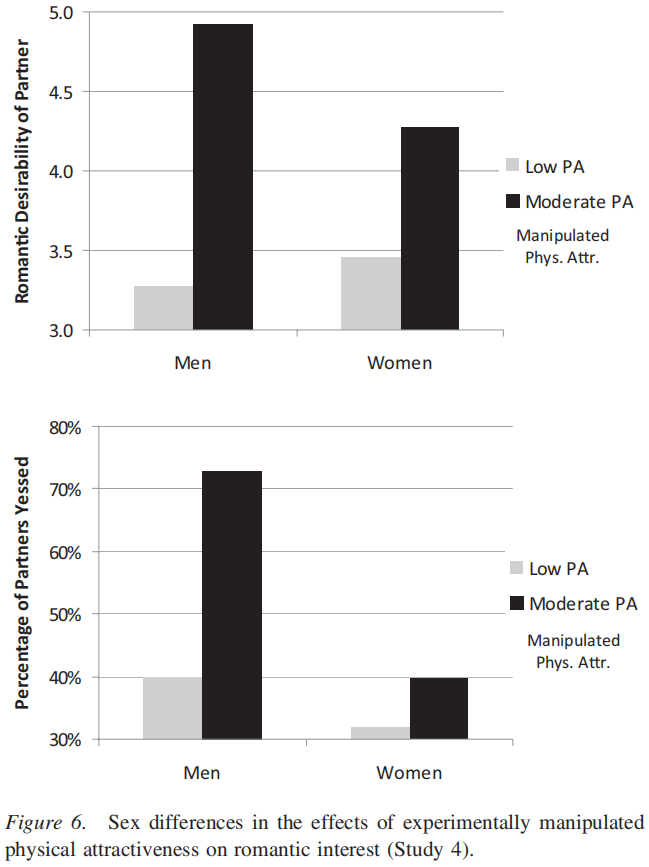

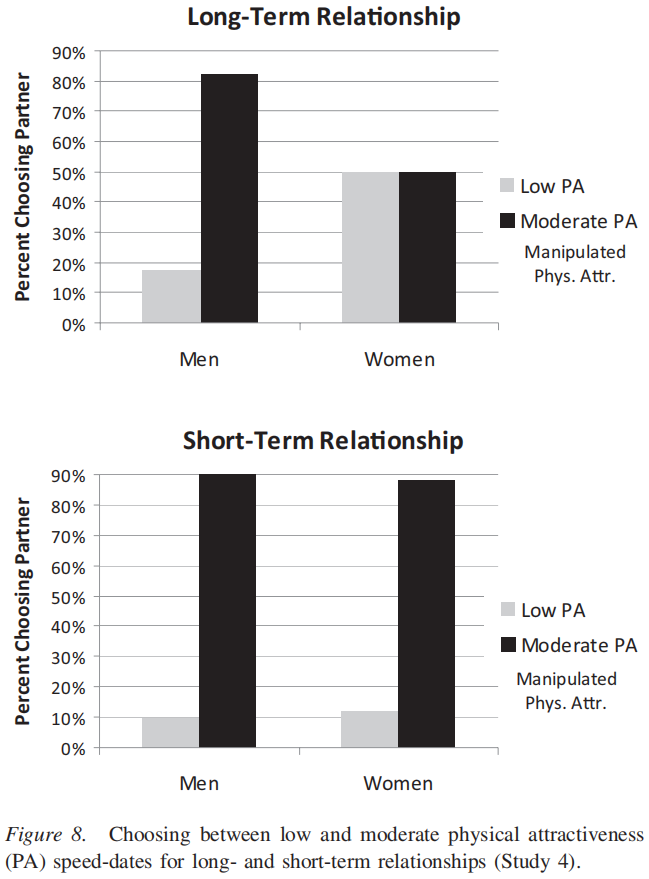

Study 4 examined mate choice in a pool with both unattractive and moderately attractive individuals.

The participants in this study were 51 men with a mean age of 23 and 42 women with a mean age of 21.5.

Photos were rated by 19-20 opposite-sex judges.

Participants stated how important physical attractiveness was to them in determining interest in a potential long-term and short-term relationship. They also rated their partner in physical attractiveness after each speed-date, and again romantic desirability and whether they’d like to exchange contact information. After completing both dates, they were asked to choose one of the two targets for a hypothetical long-term committed relationship and a short-term casual sexual relationship.

Men considered physical attractiveness to be marginally more important (5.08) than did women (4.76) for potential long-term relationships, but they didn’t differ when it came to short-term relationships (6.16).

There was a significant sex interaction effect with manipulated physical attractiveness for both romantic desirability and yessing, with men more than women reporting greater attraction and desire to date the target as their attractiveness went from low to moderate.

There was also a significant interaction effect with stated importance for long-term mates and manipulated physical attractiveness for both romantic desirability and yessing. The same wasn’t true for stated importance for short-term mates however.

When it came to long-term relationship desire, women were split between the low and moderately attractive targets, while men significantly favoured the more attractive target. For short-term desire however there was no sex difference.

They conclude from these studies that the sex difference in preferences more readily emerges when the mating pool includes people at the low end of social status and physical attractiveness, and this is where previous speed-dating studies went wrong.

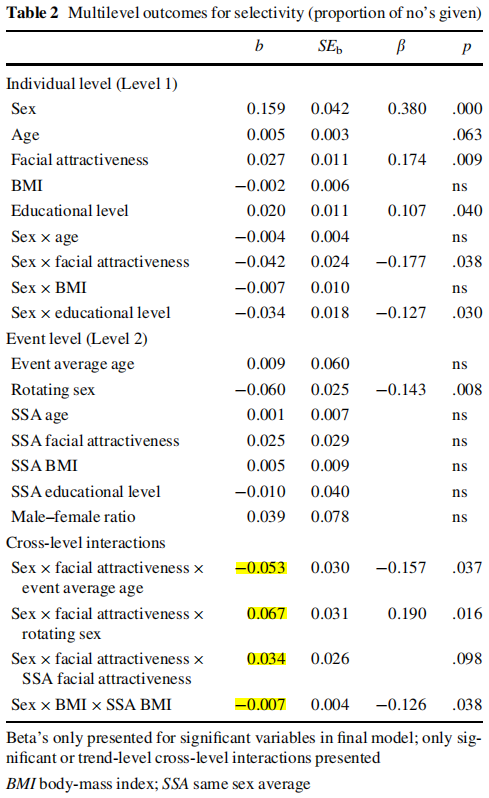

Overbeek et al. (2013): The Malleability of Mate Selection in Speed-Dating Events

270 men with a mean age of 33.3 and 276 women with a mean age of 31.7 engaged in an average of 13 speed-dates.

Their attractiveness was rated from standardized photographs by 4 independent coders. They reported their own weight and height, and highest level of education.

Women (.75) gave more no’s than men (.59), and women received more yesses (.39) than men (.23). Desirability and selectivity were correlated at .22.

No sex difference was found for the effects of facial attractiveness, BMI, or education level, but a significant sex difference emerged for age whereby older participants received less yesses than younger participants more so for women than men.

They also found that in accordance with their hypothesis that female selectivity is more malleable and context-dependent, event characteristics affected women’s but not men’s selectivity, as the trend for women with lower facial attractiveness and deviant BMI values being more selective was pronounced in the context of higher intrasexual competition, such as when women were rotated rather than men or when other women were more attractive or had a healthier BMI.

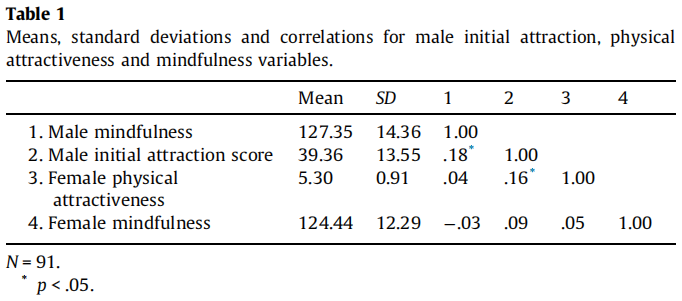

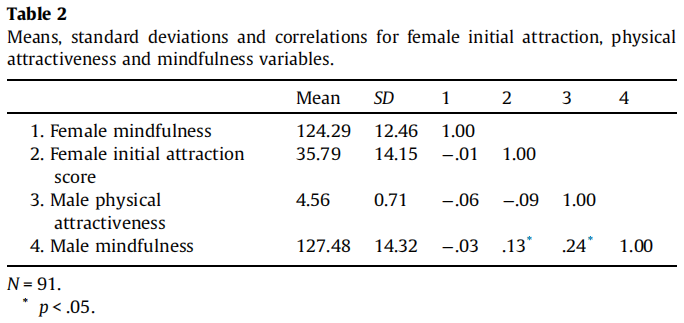

Janz et al. (2015): Individual differences in dispositional mindfulness and initial romantic attraction: A speed dating experiment

44 male undergrads with a mean age of 21.1 and 47 female undergrads with a mean age of 20.6 engaged in

Participants filled out a questionnaire relating to ‘mindfulness’, or ‘paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, non-judgementally’, and photos were rated by two independent judges.

They found that while physical attractiveness was significantly associated with male’s initial attraction, physical attractiveness wasn’t associated with female’s initial attraction. Moreover, mindfulness predicted women’s but not men’s initial attraction. These effects remained after controlling for each variable.

The takeaway from this study? Start meditating today and this could be you (metaphorically):

Selterman et al. (2015): Do Men and Women Exhibit Different Preferences for Mates? A Replication of Eastwick and Finkel (2008)

As the title implies, this study attempted to replicate the findings of Eastwick & Finkel (2008). 307 people (49.8% female) with a mean age of 19 engaged in an average of 9.3 speed-dates.

Like the previous study, perceived earning prospects showed no significant difference in the overall r, nor did physical attractiveness or personability:

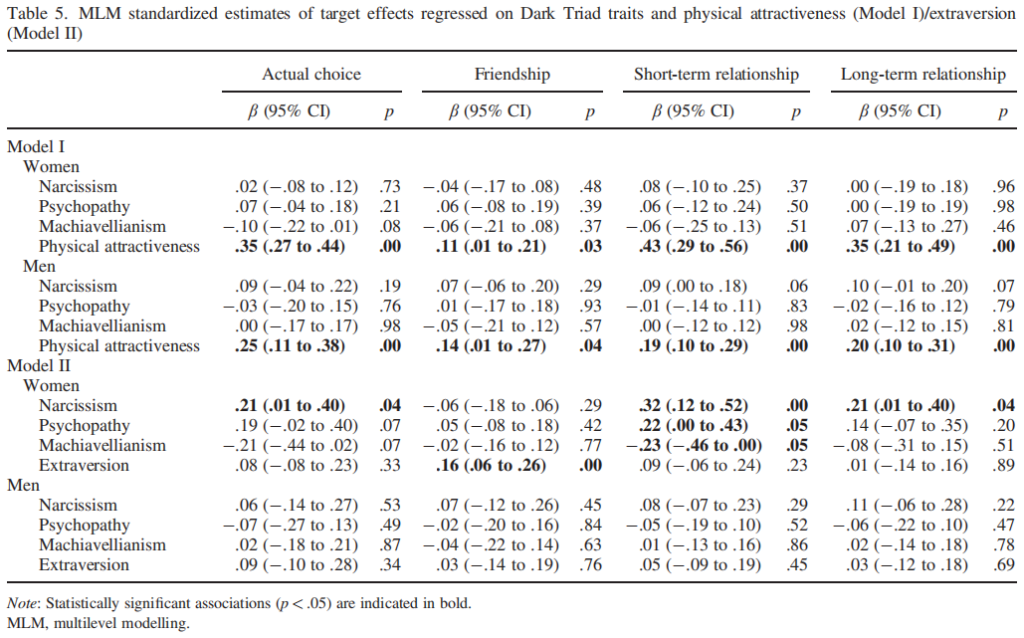

Jauk et al. (2016): How Alluring Are Dark Personalities? The Dark Triad and Attractiveness in Speed Dating

44 men and 46 women with a mean age of 22.9 attended one of three speed-dating events, for a total of 691 3 minute interactions.

Participants completed intentories measuring dark triad traits (narcissism, psychopathy, and machiavellianism) as well as big 5 traits and sociosexual orientation (the latter wasn’t relevant to this study).

Physical attractiveness ratings were made from four external raters, as partner ratings were confounded by personality/behaviour (likeability ratings correlated more with partner than external attractiveness ratings).

They related their date’s appeal for friendships, one night stands, booty calls, friends with benefits (these three being aggregated to an average short-term relationship indicator), and long-term relationships.

Women were chosen for further dates by 48% of men while men were chosen by 30% of women.

Dark triad traits significantly affected women’s likelihood of being chosen for further dates and short-term relationships, and narcissism had significant associations with short- and long-term relationship ratings for men, but these effects disappeared after controlling for physical attractiveness (though only just for men whose effect sizes remained similar, & narcissism was more related to extraversion for men).

Physical attractiveness significantly correlated with all relationship types, with significant sex differences emerging in the case of short-term relationships, predicting men’s ratings of women to a greater degree.

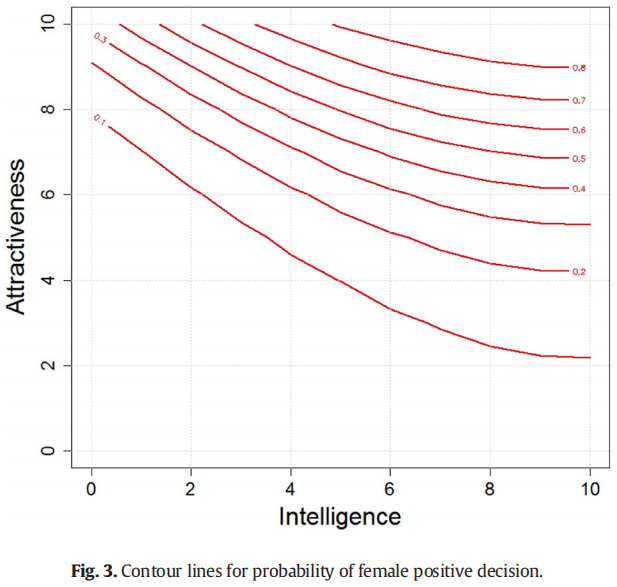

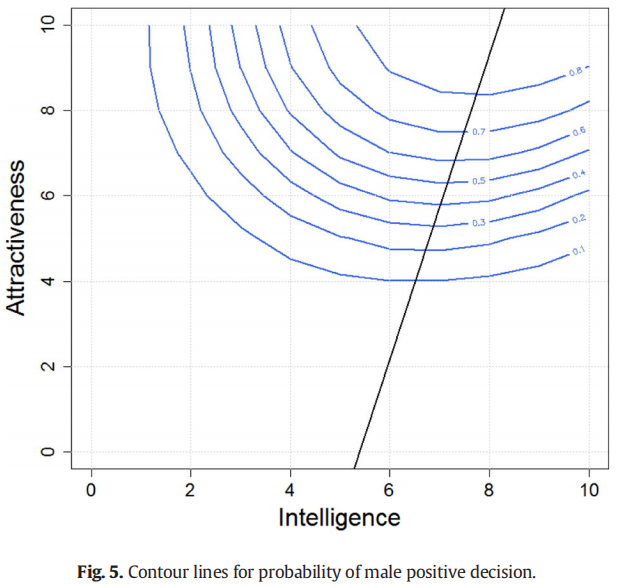

Karbowski et al. (2016): Perceived female intelligence as economic bad in partner choice

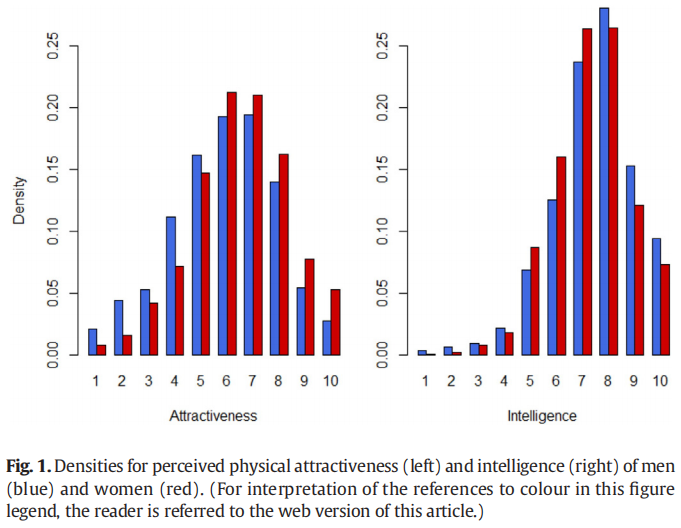

278 male and 276 female undergrads attended a series of 4 minute speed-dates, for a total of 4,184, and then evaluated them on physical attractiveness and intelligence.

More men were rated as unattractive and more women as attractive (though as usual the distribution is not as skewed as the OKC meme), but more men were rated as intelligent (but also very stupid):

Men made yes decisions 47.7% of the time and women 36.5%.

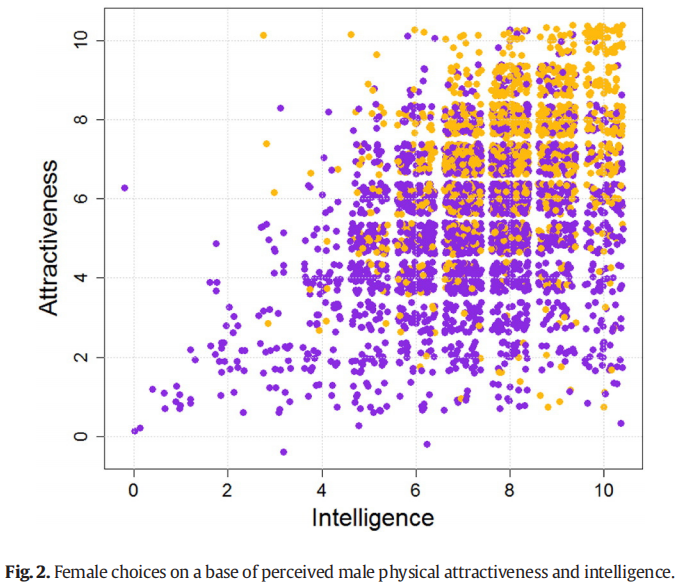

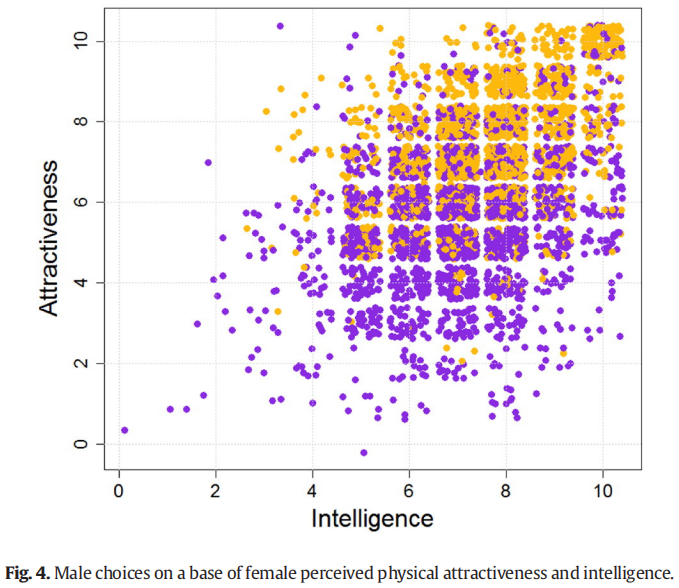

These scatterplots display women and men’s decisions by how attractive and intelligent they perceived their partners, with yellow points representing yesses and purple ones no’s:

If men were rated intelligent enough, it seems like they had a decent chance of being selected even if they were rated low on attractiveness.

In these figures we can see the rate at which people are willing to give up one point in physical attractiveness for one point in perceived intelligence while maintaining the same likelihood of being yessed:

For men, small increases in perceived intelligence had a large impact in the low intelligence region, and for men high in perceived intelligence, small increases in physical attractiveness did. It seems like it’s probably preferable to be a ‘dumb chad’ than the reverse however.

For women, this is where the title of the study comes in. When women are rated as unattractive, even with high intelligence they are far more uniformly rejected than for men where there was more variance in yesses and no’s in the bottom right quadrant. There are also fewer points in general in this area, implying that women’s perceived intelligence is more closely connected to their physical attractiveness than men’s is.

While for men intelligence always seemed to be an ‘economic good’, for women the relationship was non-monotonic, with an optimal level indicated by the black line.

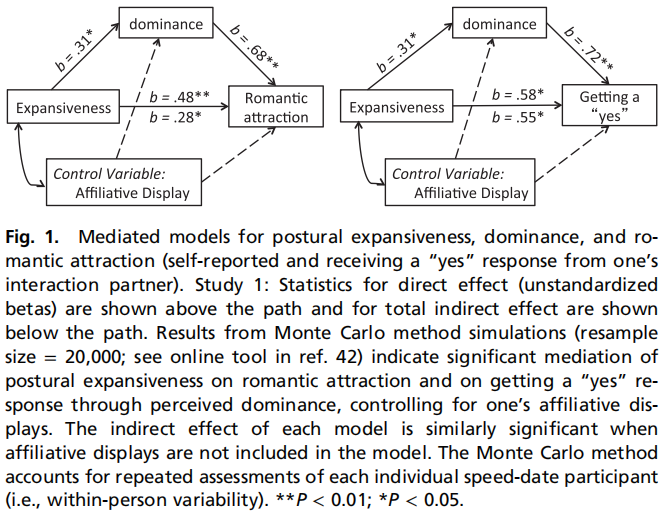

Vacharkulksemsuk et al. (2016): Dominant, open nonverbal displays are attractive at zero-acquaintance

Study 1 was a speed-dating experiment consisting of 144 4 minute speed-dates.

An open, expansive non-verbal display expressed during the date significantly predicted odds of receiving a yes. For every standard deviation increase in postural expansiveness, people were 76% more likely to receive a yes. They were also rated higher on romantic attraction. This is despite its correlation with attractiveness being weak and not significant at the .05 level.

They determined that it was significantly mediated by perceived dominance:

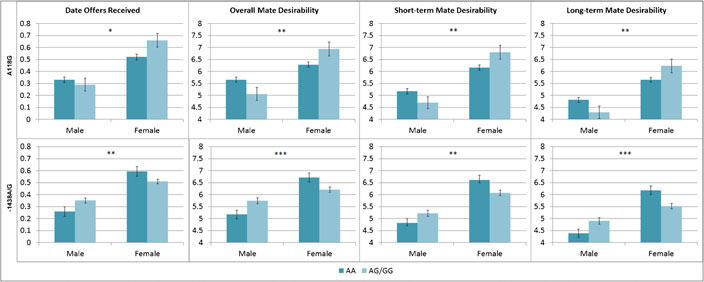

Wu et al. (2016): Gender Interacts with Opioid Receptor Polymorphism A118G and Serotonin Receptor Polymorphism −1438 A/G on Speed-Dating Success

This one is novel in that it directly examined specific genes and the effect they have on date outcomes. While black pillers use the term ‘genes’ synonymously with physical appearance however, this study looked at the A118G and −1438 A/G polymorphisms. The former has been linked to submissiveness and social sensitivity, while the latter has been linked to leadership and social dominance.

131 male and female Asian American undergrads with a mean age of 20.7 had their DNA collected and then engaged in 3 minute speed-dates with 15-22 individuals. They rated their partner’s overall desirability and their short- and long-term desirability, and the ratings received from all their partners were averaged. While men received offers 32% of the time, women did 53% of the time and were rated significantly higher in desirability.

Significant gender-by-genotype interactions were revealed, in that while the G-allele A118G was linked to greater dating success for women and less for men, the G-allele −1438 A/G was linked to greater dating success for men and less for women.

Together they explained 4-7% of the overall variance in dating success. It might not sound like much, but it’s a lot for just a couple of genes, and it’s likely there are many such genes with small effects which would add up.

These results provided support for social role theory, as they are in line with prevailing gender norms wherein women valued more for communal men more for agentic attributes.

Samani (2020): Linguistic Signaling in Speed-Dates

62 male and 72 female undergrads attended six speed-dating events for a series of 4 minute speed-dates with an average of 9.1 participants.

Participants completed a series of questionnaires, the ones included in the study being the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, the Big Five Personality Inventory, and the Experiences in Close Relationships – Revised, measuring adult attachment.

They also rated their partners in physical attractiveness and several other traits after their dates.

When asked how important men and women felt various factors were in a mate, women more than men stated that emotional stability, ambitiousness, good financial prospects, good social status, and a similar educational background were important characteristics.

However it wasn’t found that there was an association between men’s type of university major and the proportion of yesses they received.

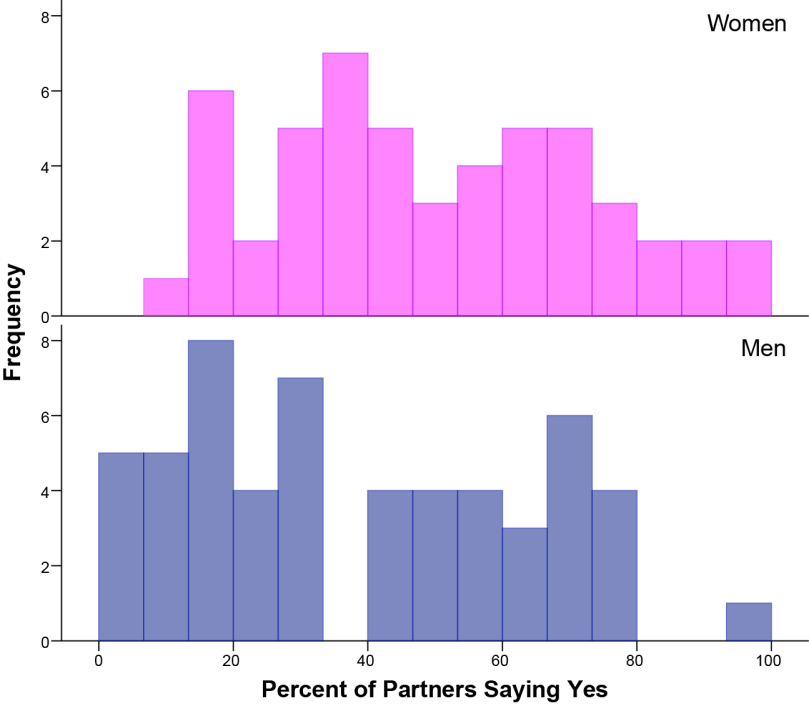

While men received yesses from 39% of their partners on average, women received them from 50%, and while 9% received no yesses at all, this wasn’t the case for any of the women:

As we can see, only a single man received yesses 100% of the time, or more than 80% of the time, compared to 6 women more than 80% of the time.

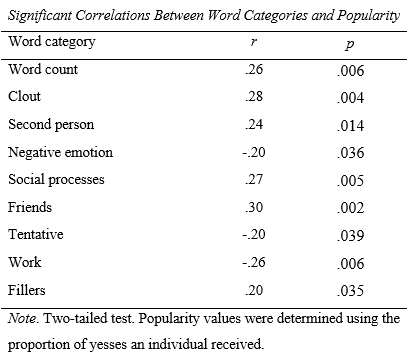

The interactions were transcribed to analyze the linguistic properties of speed-dates.

It was found that people who talked more, used more clout words, second person pronouns, words associated with social processes and friends, and filler words were more popular.

People who used more negative emotion words, tentative words, and words related to work however were less popular.

LSM (language style matching) didn’t predict mutual yessing, but perceived similarity ratings did.

Now we get to how the variables in the post-date questionnaire predicted interest. Various items were included in the three factors of ‘agreeableness’, ‘competence’, and ‘attractiveness’ if they loaded onto them at over .6.

Agreeableness was a significant predictor of dating interest for men (standardized actor effect = .24, r = .19; p < .001) and women (standardized actor effect = .323 r = .298; p < .001), and apparently this difference wasn’t significant.

Competence didn’t seem to have any effect however. It’s suggested that this may be because they were a university student sample and generally perceived each other as competent enough.

Attractiveness for men had a standardized actor effect = .567, r = .46; p < .001, and for women a standardized actor effect = .441, r = .435; p < .001. This difference was statistically significant at p = .034, with partner attractiveness predicting men’s dating interest to a greater degree.

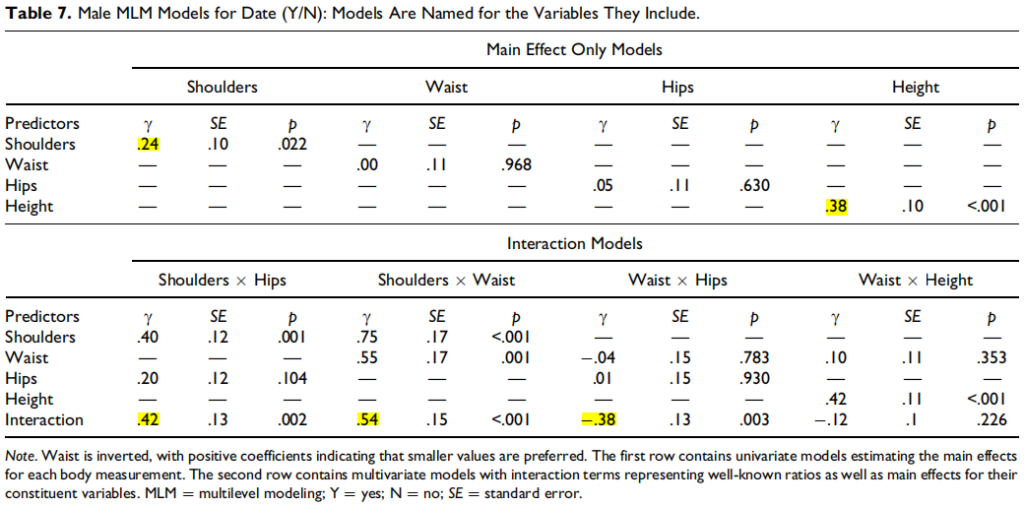

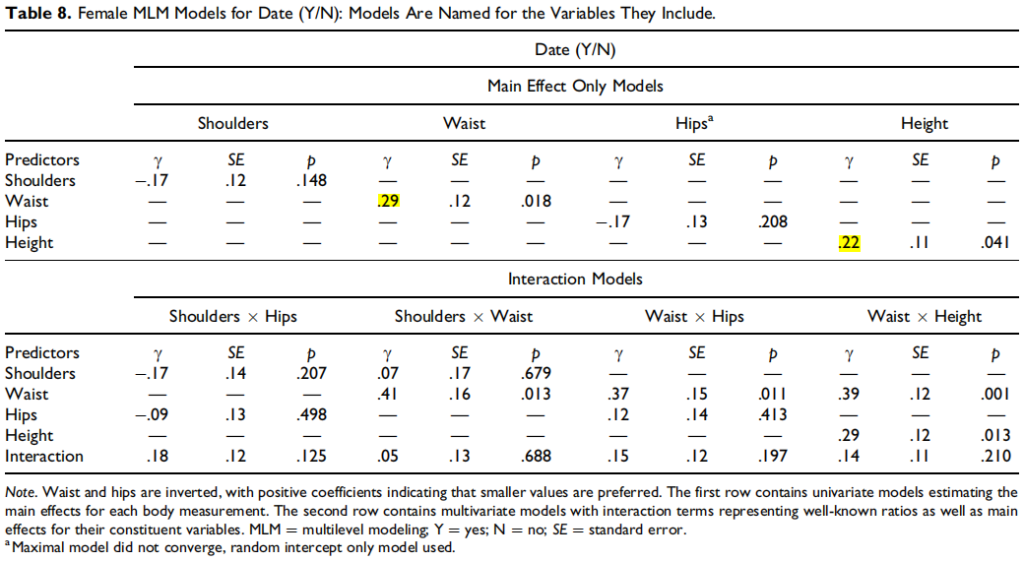

Sidari et al. (2020): Preferences for Sexually Dimorphic Body Characteristics Revealed in a Large Sample of Speed Daters

264 men with a mean age of 19.8 and 275 women with a mean age of 19.1 engaged in 2-5 3 minute speed-dates.

Participants self-reported items such as height, they rated their partners in their body, facial, personality, and overall attractiveness following their dates, then they had their body measurements measured.

Men who were taller or had broader shoulders were yessed more often. There were also interaction effects when it came to shoulder-to-waist and shoulder-to-hips ratios, as well as a negative interaction effect of waist-to-hip ratios (with waist being inverted).

Interestingly, taller women were also yessed more often, as well as women with narrower waists. The significant interaction effects when it came to attractiveness became insignificant when it came to being chosen, as did wider hips.

While there were significant sex differences in how bodily, facial, and personality attractiveness predicted overall attractiveness ratings, the differences weren’t quite significant when it came to yesses:

What would be significant however are sex differences in the disparities between both facial attractiveness and personality attractiveness, and bodily attractiveness and personality attractiveness. For instance, while the personality attractiveness coefficient was .12 higher than the bodily attractiveness coefficient for men, it was only .02 higher for women. If you combined bodily and facial attractiveness there would probably be a significant sex difference too.

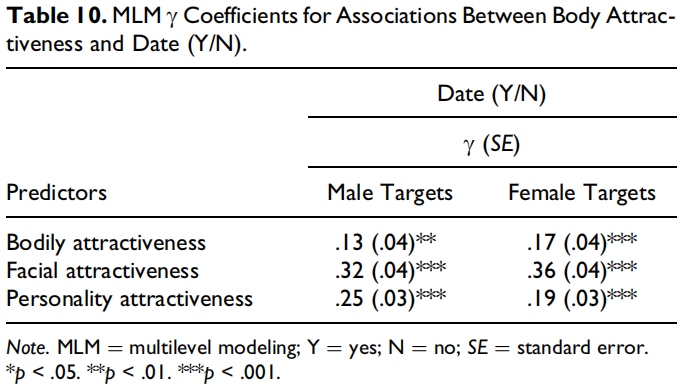

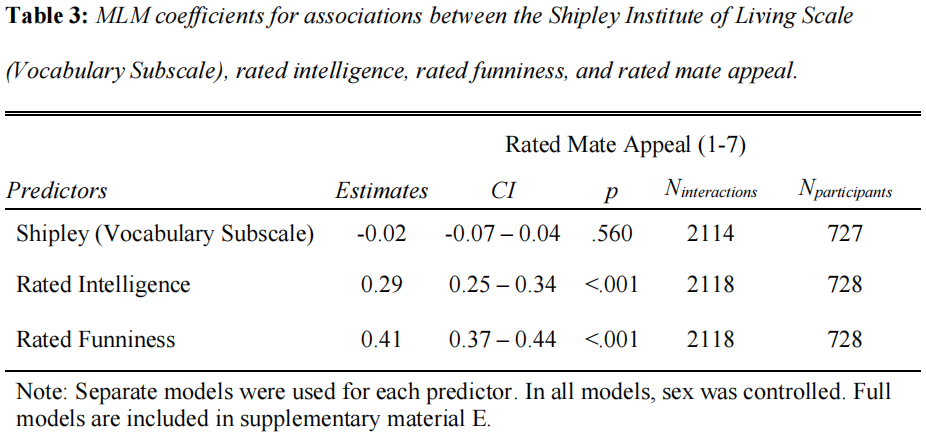

Driebe et al. (2021): Intelligence can be detected but is not found attractive in videos and live interactions

In study 2, 350 male and 379 female undergrads engaged in 2-5 3 minute speed-dates, and rated their intelligence, funniness, and mate appeal.

43.6% of women and 47.5% of men indicated hypothetical interest in going on a real date with their partners.

More intelligent people were perceived to be more intelligent by their speed-date partners (though the correlation was weak, .12).

Rated intelligence and funniness was associated with mate appeal, however measured intelligence wasn’t:

Of course the halo effect is always a valid concern, but they determined that a significant effect remained after controlling for physical attractiveness: “While our measures had the drawback that participants’ ratings of funniness could be contaminated by the halo effect of physical attractiveness, ratings of funniness still predicted mate appeal in both studies after adjusting for rated physical attractiveness”.

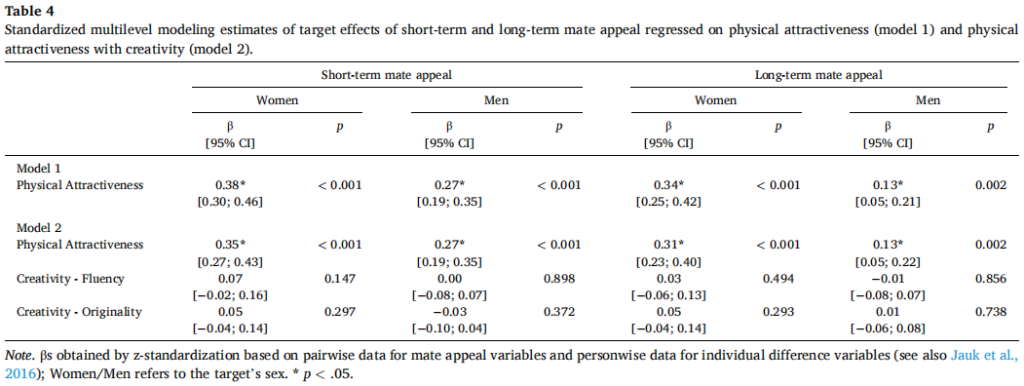

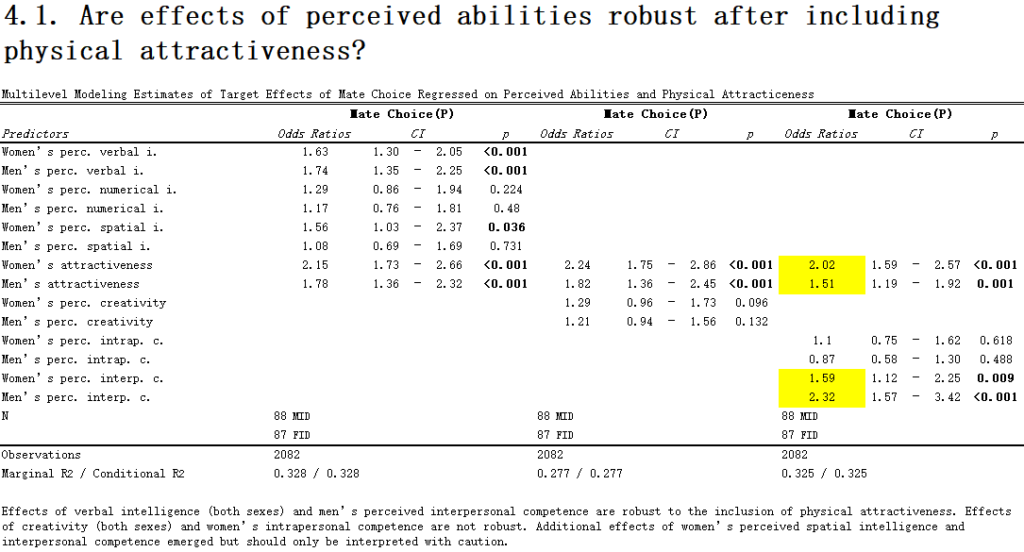

Hofer et al. (2021): What you see is what you want to get: Perceived abilities outperform objective test performance in predicting mate appeal in speed dating

88 men and 87 women with a mean age of 22.5 engaged in 11-14 3 minute speed-dates, for a total of 1,094.

They completed a series of intelligence tests, as well as one on creativity and one on emotional management abilities.

They employed 10 external judges to rate people’s physical attractiveness, because as mentioned earlier positive personality evaluations can inflate attractiveness ratings, confirmed by the fact that objective attractiveness ratings correlated at only .2 with speed-date likeability ratings, while speed-date attractiveness ratings correlated at .53 with speed-date likeability ratings.

Objectively measured intelligence facets failed to significantly predict mate appeal, nor did either type of emotional competence or creativity (the effect of creativity on women’s mate appeal was mediated by attractiveness).

Objectively rated attractiveness correlated with women being chosen at .59 and men at .46.

Mean speed-date attractiveness ratings however correlated at .86 with women being chosen and .76 with men being chosen. This difference again likely reflects the influence that non-appearance factors have on partner-rated attractiveness.

A significant sex difference was found whereby objectively rated physical attractiveness predicted men’s long- and short-term mate appeal to a greater degree (the gap for short-term mate appeal appeared to become not quite significant after including creativity in the model):

While objective cognitive abilities failed to significantly predict mate appeal, perceived abilities had strong effects.

They tested whether they held after controlling for attractiveness.

The effects of perceived verbal intelligence remained significant (all β ≥ .11 p ≤ .013), while women’s perceived numerical intelligence was no longer predictive of their long-term mate appeal. Men’s perceived creativity was still a positive predictor of their short-term mate value (β = .08, p = .029), though it no longer predicted each gender’s long-term mate value. Women’s perceived intrapersonal competence no longer predicted their short- or long-term mate appeal, but men’s interpersonal competence was still predictive of their short- and long-term mate appeal (both β ≥ .2, both p < .001).

They then ran a regression analysis on perceived abilities and physical attractiveness.

In the model including perceived intra/interpersonal abilities and attractiveness, it was found that there was a significant difference in the effect of attractiveness with the odds ratio for women being chosen being 2.02 and for men 1.51.

Perceived interpersonal competence was even a stronger predictor than attractiveness of men being chosen, with an odds ratio of 2.32, and for women 1.59.

Like the previous study, actual intelligence didn’t seem to confer any benefit to people’s mate appeal, so we can safely rule out sapiosexuality from being a common orientation.

However, perceived abilities had a strong effect, and this effect survived the partialling out of physical attractiveness.

In terms of perceived intelligence, the verbal component had by far the greatest effect (women’s perceived spatial intelligence was the only other significant effect), and perceived interpersonal but not intrapersonal intelligence was strongly associated with being chosen.

Therefore it seems like we may be looking at traits which could be described as a proxy for ‘charisma’, which is a bit of an elusive concept that’s hard to pin down, and for the most part remains something that ‘you know when you see’.

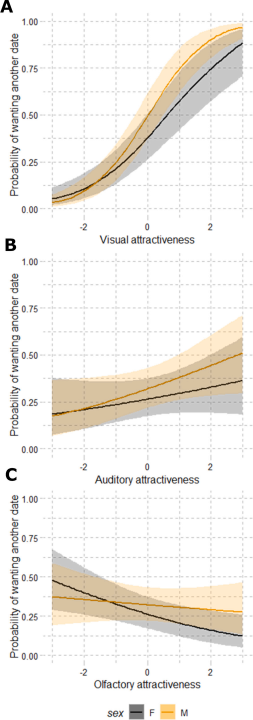

Roth et al. (2021): Multimodal mate choice: Exploring the effects of sight, sound, and scent on partner choice in a speed-date paradigm

67 participants with a mean age of 22 for women and 22.5 for men engaged in 277 4 minute speed-dates.

Participants had their faces photographed, had their voice recorded, and brought a worn t-shirt to serve as the olfactory stimuli. They then rated 10 opposite-sex participants on the stimuli they provided.

They also rated their attractiveness after their speed-dates.

When it came to yesses, physical attractiveness of course was the clear winner, with auditory attractiveness having a small effect on men’s probability of yessing their partners but not on women’s, and olfactory attractiveness if anything negatively predicting women’s yesses (so much for ‘just take a shower bro’), with no effect found for men.

Because the modalities showed some intercorrelation they ran some independent regressions and found that auditory attractiveness had more of an effect on women’s decisions, but still wasn’t quite significant at the 89% confidence level.

They also found a robust sex difference in the visual domain, with physical attractiveness predicting men’s decisions to a greater extent:

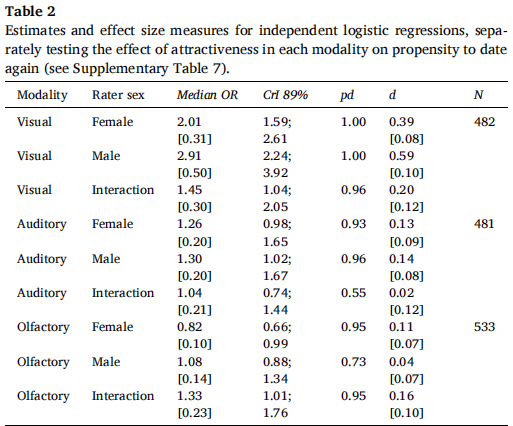

Baxter et al. (2022): Initial impressions of compatibility and mate value predict later dating and romantic interest

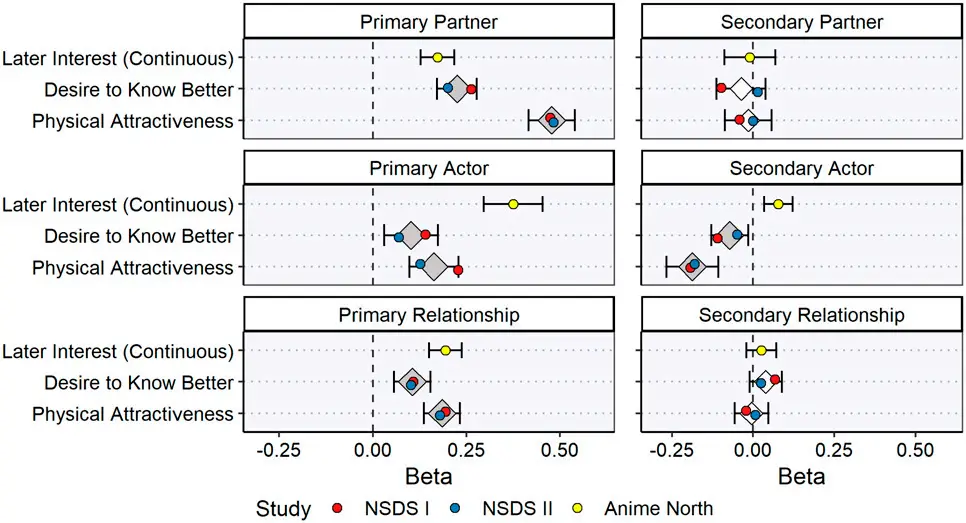

In an alaysis of 3 speed-dating studies with longitudinal follow-ups, they investigated whether different components of initial romantic impressions predicted later romantic outcomes and relationship initiation.

Partner effects refer to a date’s consensual desirability. Actor effects refer to a participant’s selectivity. Relationship effects refer to a participant’s unique liking for a date over a beyond the other two effects.

It was found that across 6,100+ follow-up reports, partner effects had the strongest overall influence on the dichotomous outcomes of contact initiation, hang out or correspond, and later romantic interest, and relationship effects had the next strongest influence. Actor effects appeared to be basically irrelevant.

Actor effects had some effect when it came to the continuous outcomes of later interest, know better, and physical attractiveness however.

These results show that not only ‘objective’ mate value but also compatibility matters. They note how in our evolutionary past getting along with one’s partner would’ve made rearing children a lot easier.

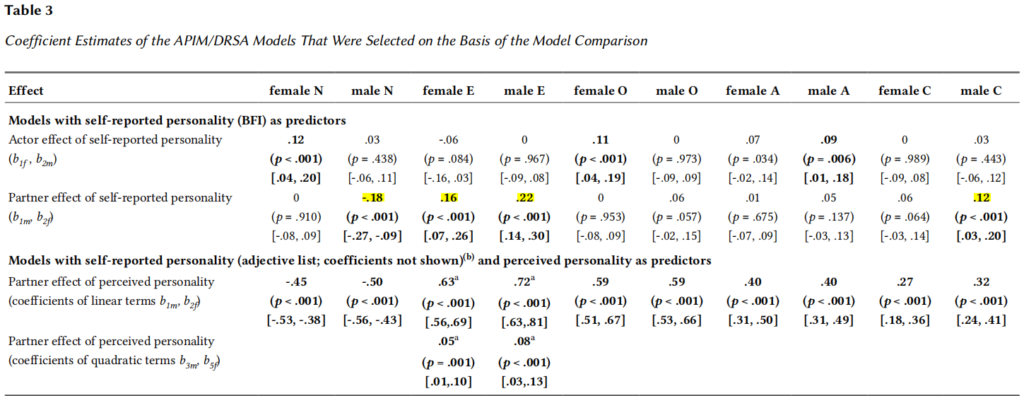

Humberg et al. (2023): Is (Actual or Perceptual) Personality Similarity Associated With Attraction in Initial Romantic Encounters? A Dyadic Response Surface Analysis

This study employed data from 2015 from the ‘Date me for Science’ study, of 200 men and 200 women with a mean age of 22.9 engaged in 3 minute speed-dates across 42 events.

Participants filled out the Big Five Inventory personality scale, as well as an adjective list, from which they constructed a two-item scale for each big 5 trait.

Men’s neuroticism was negatively associated with women’s romantic attraction towards them, while extraversion and conscientiousness were positively associated with it. Women’s extraversion was positively associated with men’s romantic attraction towards them.

No effects of similarity were found however.

External Validity?

Extrapolations from speed-dating studies have been criticized due to the brief nature of the encounters, which one may conclude renders it an overly ‘superficial’ format. After all, how much can you reasonably assess in someone beyond physical appearance in the span of a few minutes?

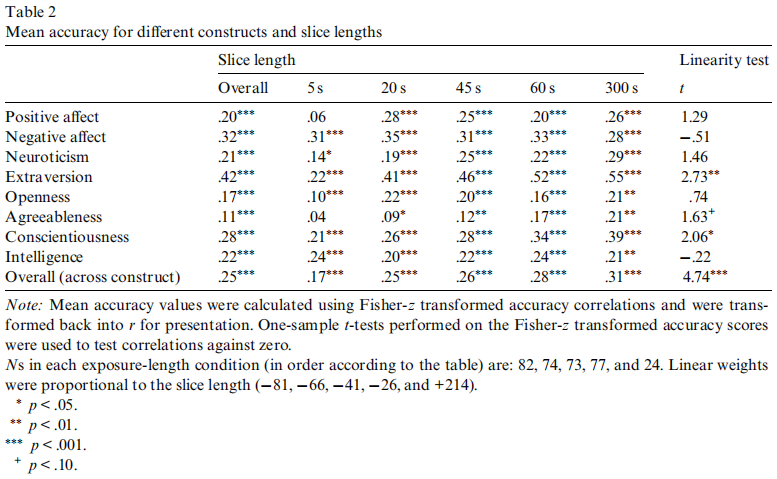

There is however a solid body of research demonstrating that people’s snap judgements based on ‘thin-slices’, or limited information, have at least a reasonable degree of accuracy (Ambady et al., 2000).

For instance, in Carney et al. (2007), judge ratings of emotionality, personality traits & intelligence correlated at .31 with the ‘objective measurements’ after 5 minutes (only up .03 from after 1 minute, but up .14 from after 5 seconds):

To the extent that these traits are relevant to mate selection, it’d also likely be beneficial to be able to quickly and accurately evaluate them.

At the same time, Kerr et al. (2020) found lower levels of accuracy in personality perception in a speed-dating paradigm than is typically seen in initial platonic interactions.

Of course the initial screening stage is crucial as it determines whether you get your foot in the door, but it’s not the beginning and end of dating. Mate retention is another aspect to consider.

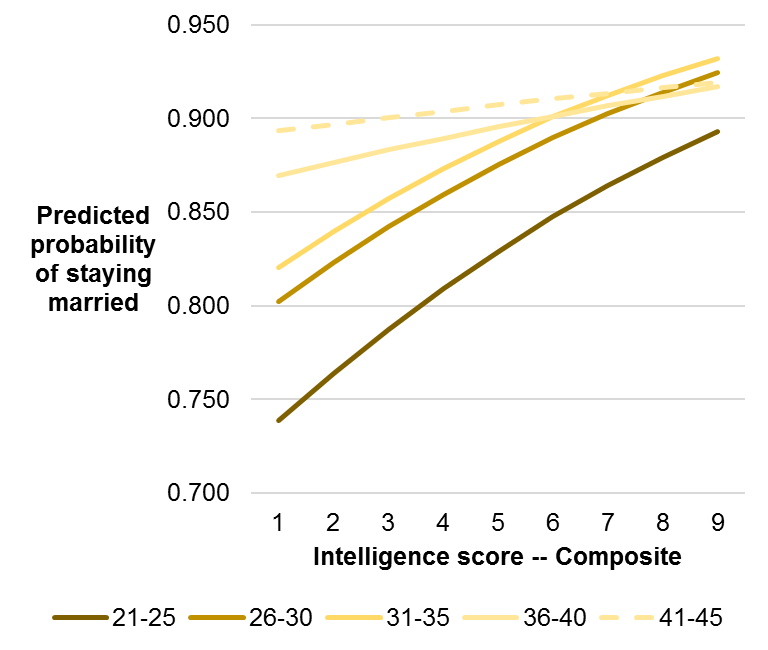

Aspara et al. (2018) found that men with higher intelligence were more likely to get and also stay married:

Walker et al. (2023) found that the extrinsic emotion regulation processes of humour, receptive listening, and valuing predicted relationship satisfaction.

Fultz et al. (2023) found that at first zero-acquaintance, where only appearance-based cues were available, unsurprisingly only attractiveness was associated with liking.

After a 5 minute interaction however, self-reported expressivity also had an effect, and then an effect of observer-rated nonverbal expressivity on liking emerged after 9 weeks of having known their group members.

Women also reported liking their group members significantly more than men did after 9 weeks, indicating that women’s judgments may be especially influenced by factors beyond those which are discernable from a brief interaction.

So certain traits may play a more prominent role in the later stages of courtship.

A relevant even if not huge number of people do in fact meet their partners through this method, about 1-2% of 18-29 Americans according to a YouGov tracker.

It’s probably comparable to meeting people at a bar/club or party, just more structured.

The studies such as Asendorpf et al. (2011) which have tracked longitudinal outcomes haven’t showed the most promising results, but it’s hard to say exactly how they compare to outcomes when it comes to meeting people through other avenues.

Of course a growing number are also meeting their partners online, where the visual element is even more prominent than in these brief but at least face-to-face interactions.

Conclusion

Let’s summarize the main findings:

- Of the traits which were measured, physical attractiveness was consistently the one with the single most predictive power for both genders.

- While it wasn’t a very consistent finding, indicating that the difference isn’t too large, in at least 10 studies physical attractiveness influenced men’s decisions more than women’s. In no study however was there a stronger effect going the other way, with the exception of the first, but that used self-reported attractiveness which is unreliable, and even there women’s BMI had a much larger effect than any other variable.

- Height tended to have an effect on men’s desirability but it was quite weak. Bodily attractiveness overall wasn’t more predictive of men’s success either.

- Many traits outside of physical appearance had a significant effect on men’s desirability, often after controlling for physical attractiveness, including perceived intelligence, personability, earning prospects, nonverbal immediacy behaviours, big 5 traits (especially extraversion & neuroticism), sport activity, occupation, attachment anxiety, perceived attachment anxiety & avoidance, vocal attractiveness, education, income, sociosexuality, shyness, dominance, grooming, anxiety & depression, mindfulness, postural expansiveness, genetic social dominance & submissiveness, agreeable personality (not necessarily the same as ‘agreeableness’), personality attractiveness, perceived funniness, perceived verbal intelligence, and perceived interpersonal competence. Of course there is likely overlap between many of these traits.

- Social status/earning potential wasn’t always or strongly associated with men’s desirability however.

- While women were consistently more selective, the ratio wasn’t 80:20 but generally close to 45:30, and it wasn’t on the basis of physical attractiveness.

- Stated preferences didn’t have much relation to ‘revealed preferences’.

- Similarity effects aren’t consistently found in initial decisions, but they seem to be present among dyads that continue to date.

Clear evidence didn’t emerge for either the evolutionary psychology or the black pill narrative.

When it comes to the evopsych predictions, while in the studies which did show a larger effect of attractiveness for one gender it was in the expected direction, it wasn’t a consistent or stark disparity.

Education and economic prospects, whether perceived or objective, didn’t have consistent or terribly large effects either, although when it did emerge it also tended to be in the expected direction.

It could be that preferences have converged considerably since women are more economically independent and it’s harder to stand out in this domain.

When it comes to the black pill, it would predict higher correlations with the physical attractiveness of targets and women’s decisions, as it states that looks matter at least as much to women, maybe more, but that women are also more selective on this basis.

Since we don’t see a higher correlation among women’s decisions and the target’s physical attractiveness, whether rated by partners or external judges, their extra selectivity is either acting upon non-physical traits, or they’re just less prone to playing the numbers game and making a lot of offers than men are.

While it may be true that men are more willing to drop their standards in the context of hookups, this doesn’t seem to translate to dating.

While there were more unpopular men (Samani, 2020), there were also less highly popular men. So it’s not the case that these results reflect a ‘chadopoly’, which would imply more skew for men, with a small concentration of men getting most of the yesses.

Another study which wasn’t included is Houser et al., 2007: Predicting Relational Outcomes: An Investigation of Thin Slice Judgments in Speed Dating.

9 men gave negative responses, compared to 18 women, in line with women’s greater disgust sensitivity which is especially pronounced in the sexual domain (Al-Shawaf et al., 2014). 62 men and 63 women gave positive responses. They could offer multiple reasons, and more women took this opportunity, adding about 30% to both positive and negative reasons.

When it came to men’s negative reasons, they were all related to attraction. When it came to women’s, 12 of the 24 reasons given were related to attraction, and 9 were to negative qualities mostly relating to personality and communication skills.

Of course black pillers will say that these other reasons are just codewords for ugly too, but there are probably good reasons for women to be more critical of certain personality characteristics as it’s important from a reproductive fitness POV them to find a guy who is likely to be a committed and reliable provider. Women’s parental investment is virtually guaranteed however.

Another speed-dating study, Arantes et al. (2021): “Time Slows Down Whenever You Are Around” for Women but Not for Men, may be relevant here, as it was found that for women, when interacting with a man they found attractive, time slowed down. Not literal time dilation obviously, but they reported the interaction taking longer than it did in reality. For men interacting with a woman they found attractive on the other hand, time sped up. One interpretation of this is that the women were using cognitive resources to search for other mate cues, while the men just wanted to race to the finish line.

One thing that we can’t deny however is that ‘looks matter’. Although in reality this isn’t likely to be a shocking revelation to too many people, black pillers may be right at least in that some may have undervalued it or exaggerated the gap in how much men and women value it.

While physical attractiveness may be the single most important trait (though a few found larger effects elsewhere for men), all these other traits relating to personality, body language, & social status surely must add up to something that’s at least worth consideration, which is more than the reductive black pill would expect.

And this is in the context of a 3-5 minute chat, where while you might be able to tell a surprising amount about someone from it, it probably won’t tell the full story.

Still, the initial screening stage is again vital, as in many cases it will act as a barrier, especially as people’s interactions move more towards the online space.

References

Buss, D. M. (1989). Sex differences in human mate preferences: Evolutionary hypotheses tested in 37 cultures. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 12(1), 1–49. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X00023992

Kurzban, R., & Weeden, J. (2005). HurryDate: Mate preferences in action. Evolution and Human Behavior, 26(3), 227–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2004.08.012

Fisman, R., Iyengar, S. S., Kamenica, E., & Simonson, I. (2006). Gender differences in mate selection: Evidence from a speed dating experiment. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 121(2), 673–697. https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.2006.121.2.673

Todd, P. M., Penke, L., Fasolo, B., & Lenton, A. P. (2007). Different cognitive processes underlie human mate choices and mate preferences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 104(38), 15011–15016. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0705290104

Eastwick, P. W., & Hunt, L. L. (2014). Relational mate value: Consensus and uniqueness in romantic evaluations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 106(5), 728–751. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035884

Eastwick, P. W., & Finkel, E. J. (2008). Sex differences in mate preferences revisited: Do people know what they initially desire in a romantic partner? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94(2), 245–264. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.94.2.245

Houser, M. L., Horan, S. M., & Furler, L. A. (2008b). Dating in the fast lane: How communication predicts speed-dating success. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 25(5), 749–768. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407508093787

Luo, S., & Zhang, G. (2009). What leads to romantic attraction: similarity, reciprocity, security, or beauty? Evidence from a speed-dating study. Journal of personality, 77(4), 933–964. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00570.x

Lenton, A. P., & Francesconi, M. (2010). How humans cognitively manage an abundance of mate options. Psychological science, 21(4), 528–533. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797610364958

McClure, M. J., Lydon, J. E., Baccus, J. R., & Baldwin, M. W. (2010). A signal detection analysis of chronic attachment anxiety at speed dating: being unpopular is only the first part of the problem. Personality & social psychology bulletin, 36(8), 1024–1036. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167210374238

Asendorpf, J. B., Penke, L., & Back, M. D. (2011). From Dating to Mating and Relating: Predictors of Initial and Long–Term Outcomes of Speed–Dating in a Community sample. European Journal of Personality, 25(1), 16–30. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.768

Eastwick, P. W., Eagly, A. H., Finkel, E. J., & Johnson, S. E. (2011). Implicit and explicit preferences for physical attractiveness in a romantic partner: a double dissociation in predictive validity. Journal of personality and social psychology, 101(5), 993–1011. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024061

Humbad, M. N. (2012). Exploring mate preferences from an evolutionary perspective using a speed dating design. Doctoral dissertation. https://d.lib.msu.edu/etd/1485

Li, N. P., Yong, J. C., Tov, W., Sng, O., Fletcher, G. J., Valentine, K. A., Jiang, Y. F., & Balliet, D. (2013). Mate preferences do predict attraction and choices in the early stages of mate selection. Journal of personality and social psychology, 105(5), 757–776. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033777

Overbeek, G., Nelemans, S. A., Karremans, J., & Engels, R. C. (2013). The malleability of mate selection in speed-dating events. Archives of sexual behavior, 42(7), 1163–1171. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-012-0067-8

Janz, P., Pepping, C. A., & Halford, W. K. (2015). Individual differences in dispositional mindfulness and initial romantic attraction: A speed dating experiment. Personality and Individual Differences, 82, 14–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.02.025

Selterman, D., Chagnon, E., & Mackinnon, S. P. (2015). Do men and women exhibit different preferences for mates? A Replication of Eastwick and Finkel (2008). SAGE Open, 5(3), 215824401560516. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244015605160

Jauk, E., Neubauer, A. C., Mairunteregger, T., Pemp, S., Sieber, K. P., & Rauthmann, J. F. (2016). How alluring are dark personalities? The dark triad and attractiveness in speed dating. European Journal of Personality, 30(2), 125–138. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.2040

Karbowski, A., Deja, D., & Zawisza, M. (2016). Perceived female intelligence as economic bad in partner choice. Personality and Individual Differences, 102, 217–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.07.006

Vacharkulksemsuk, T., Reit, E., Khambatta, P., Eastwick, P. W., Finkel, E. J., & Carney, D. R. (2016). Dominant, open nonverbal displays are attractive at zero-acquaintance. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113(15), 4009–4014. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1508932113

Wu, K., Chen, C., Moyzis, R. K., Greenberger, E., & Yu, Z. (2016). Gender Interacts with Opioid Receptor Polymorphism A118G and Serotonin Receptor Polymorphism -1438 A/G on Speed-Dating Success. Human nature (Hawthorne, N.Y.), 27(3), 244–260. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12110-016-9257-8

Sidari, M. J., Lee, A. J., Murphy, S. C., Sherlock, J. M., Dixson, B. J., & Zietsch, B. P. (2020). Preferences for sexually dimorphic body characteristics revealed in a large sample of speed daters. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 12(2), 225–236. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550619882925

Samani, N. M. V. (2020). Linguistic Signaling in Speed-Dates. Doctoral dissertation. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=9795&context=etd

Driebe, J. C., Sidari, M. J., Dufner, M., Von Der Heiden, J. M., Bürkner, P., Penke, L., Zietsch, B. P., & Arslan, R. C. (2021). Intelligence can be detected but is not found attractive in videos and live interactions. Evolution and Human Behavior, 42(6), 507–516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2021.05.002

Hofer, G., Burkart, R., Langmann, L., & Neubauer, A. C. (2021b). What you see is what you want to get: Perceived abilities outperform objective test performance in predicting mate appeal in speed dating. Journal of Research in Personality, 93, 104113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2021.104113

Roth, T. S., Samara, I., & Kret, M. E. (2021). Multimodal mate choice: Exploring the effects of sight, sound, and scent on partner choice in a speed-date paradigm. Evolution and Human Behavior, 42(5), 461–468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2021.04.004

Baxter, A., Maxwell, J. A., Bales, K. L., Finkel, E. J., Impett, E. A., & Eastwick, P. W. (2022). Initial impressions of compatibility and mate value predict later dating and romantic interest. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 119(45), e2206925119. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2206925119

Humberg, S., Gerlach, T. M., Franke-Prasse, T., Geukes, K., & Back, M. D. (2023). Is (actual or perceptual) personality similarity associated with attraction in initial romantic encounters? A dyadic response surface analysis. Personality Science, 4. https://doi.org/10.5964/ps.7551

Ambady, N., Bernieri, F. J., & Richeson, J. A. (2000). Toward a histology of social behavior: Judgmental accuracy from thin slices of the behavioral stream. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology, Vol. 32, pp. 201–271). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(00)80006-4

Carney, D. R., Colvin, C. R., & Hall, J. A. (2007). A thin slice perspective on the accuracy of first impressions. Journal of Research in Personality, 41(5), 1054–1072. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2007.01.004

Kerr, L. G., Tissera, H., McClure, M. J., Lydon, J., Back, M. D., & Human, L. J. (2020). Blind at First Sight: the role of distinctively accurate and positive first impressions in romantic interest. Psychological Science, 31(6), 715–728. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797620919674

Aspara, J., Wittkowski, K., & Luo, X. (2018). Types of intelligence predict likelihood to get married and stay married: Large-scale empirical evidence for evolutionary theory. Personality and Individual Differences, 122, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.09.028

Setty, E., & Dobson, E. (2023). An Exploration of Healthy and Unhealthy Relationships Experienced by Emerging Adults During the Covid-19 Lockdowns in England. Emerging Adulthood, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/21676968231200094

Fultz, A. A., Stosic, M. D., & Bernieri, F. J. (2023). Nonverbal expressivity, physical attractiveness, and liking: first impression to established relationship. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10919-023-00444-7

Arantes, J., Pinho, M., Wearden, J., & Albuquerque, P. B. (2021). “Time Slows Down Whenever You Are Around” for Women but Not for Men. Frontiers in psychology, 12, 641729. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.641729

A major point of weakness in many of these studies is the method of rating the subjects attractiveness. Typically the opinions of a couple of dozen opposite sex rater is employed to categorize subject attractiveness. Usually a group of college girls are shown a few photographs and asked to rate their personal evaluation of the fellows to be used in the studies.

This seems far too arbitrary a technique to arrive at the lads’ “good looks”. It seems a terribly arbitrary an evaluation. Let me suggest that this is more problematic to a study’s integrity than too low an n number.