Is Autism The Real Black Pill?

Perhaps the trait most conventionally associated with men doing poorly with women (at least until recently) is ‘social ineptitude’, or having ‘no rizz’ as the zoomers are apparently calling it. This is a description of the main character in ‘The 40-Year-Old Virgin’ for instance:

Andy Stitzer is a shy 40-year-old introvert who works as a stock supervisor at electronics store Smart Tech. He gave up trying to have sex after various failed attempts and lives alone in an apartment with a collection of action figures and video games.

Wikipedia

Of course it won’t always be explicitly identified as ‘autism’, but it naturally follows that men suffering from a disorder characterized primarily by social communication impairments will encounter the most intense manifestation of these challenges.

There have been a few Netflix series recently made around this premise such as Love on the Spectrum and Atypical. At least half of the male cast of the UK show ‘The Undateables’ also had autism. Apparently autistic men trying to interact with women carries an allure akin to that of a freak show.

Although it may still be understudied compared to other aspects of autism, there have been some empirical studies which have touched upon this issue, so let’s see just how dire the situation is for socially crippled men (and possibly women?).

Studies

Cederlund et al. (2008): Asperger Syndrome and Autism: A Comparative Longitudinal Follow-Up Study More than 5 Years after Original Diagnosis

Of 70 men with Asperger’s (M age = 21.5), three were living in a relationship (4%) and 10 (14%) had had relationships for varying periods of time in the past. This leaves a whopping 82% who’d apparently been forever alone.

Hofvander et al. (2009): Psychiatric and psychosocial problems in adults with normal-intelligence autism spectrum disorders

Of 122 autistic people of normal intelligence (67% male; Median age = 29), just 19 (16%) had lived in a long-term relationship.

Del Giudice et al. (2010): The evolution of autistic-like and schizotypal traits: a sexual selection hypothesis

The hypothesis they set out to test was that autistic traits were selected for following the agricultural revolution, as it created a greater dependence on systematic reasoning and technology, and the inter-generational transfer of resources enabled long-term strategies to become more viable.

They also suggest this may be at least partially responsible for the sex disparity in autism prevalence, as resource acquisition and parental investment cues would’ve been selected for more strongly in men.

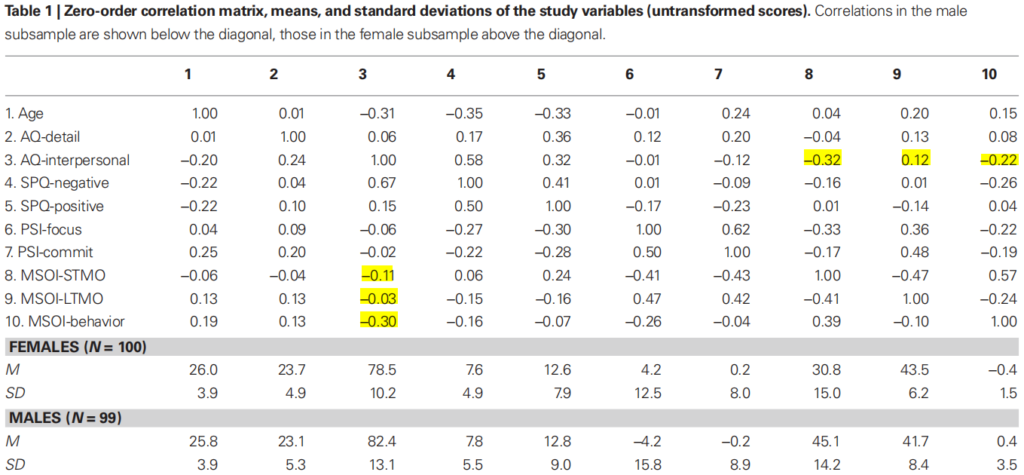

200 heterosexual unmarried adults (50% male; M age = 25.9) participated in the study.

They didn’t sample actual autistic people (though some of them may have been), but employed the Autism Spectrum Quotient (AQ) which measures autistic traits in both clinical and non-clinical samples. Not all ‘normies’ are equally normie, so to speak.

They also employed the Multidimensional Sociosexual Orientation Inventory, consisting of three scales. Two attitude scales, measuring short and long-term mating orientation, and a third one measuring behaviour, which asks about the total number of sexual partners, casual sexual partners, and the number of sexual partners in the past year.

AQ-interpersonal refers to all the subscales outside of detail, namely communication, social skills, attention switching, and imagination, and is presumably more relevant to interactions with the opposite-sex.

We find a -.3 correlation between AQ-interpersonal and MSOI-behavior for men, meaning that men scoring higher in AQ-interpersonal had less sexual experience.

This would typically be considered to be in the weak to moderate range. However to put it into perspective, physical attractiveness tends to correlate at around .14, and height at around .05, so this would still explain about 3x as much of the variance in sexual experience as these physical traits.

It doesn’t look like it had a significant correlation with MSOI-STMO or MSOI-LTMO for men either, but MSOI-STMO did have a negative correlation for women higher in AQ-interpersonal, implying that more autistic women are less short-term oriented. This may partly explain why AQ-interpersonal also had a negative correlation with MSOI-behavior for women.

In their model they found that overall AQ-interpersonal reduced mating effort, while AQ-detail increased long-term investment, so it may be the case that different components affect mating strategies in different ways.

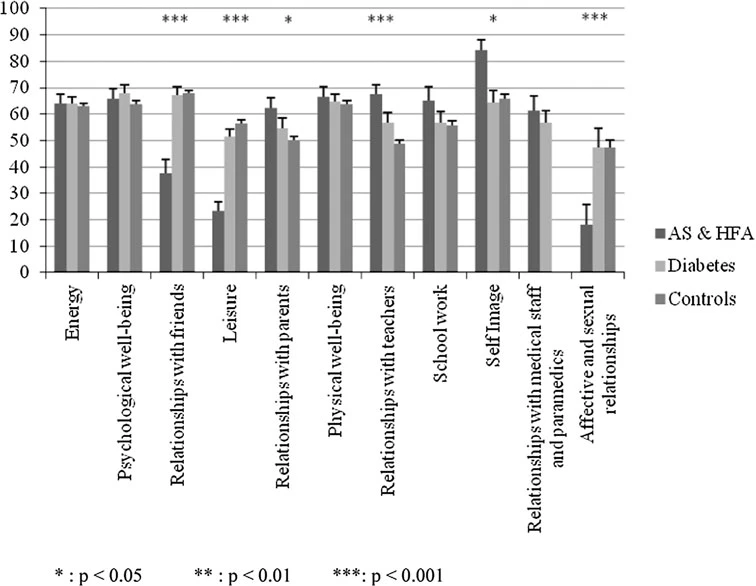

Cottenceau et al. (2012): Quality of life of adolescents with autism spectrum disorders: comparison to adolescents with diabetes

26 high-functioning autistic (M age = 15), 44 diabetic (M age = 14.3), and 250 control adolescents (M age = 14.8) participated in this study.

The autistic adolescents had a significantly lower level of quality of life in the areas of relationships with friends and affective and sexual relationships than the diabetic and control groups who didn’t differ from each other.

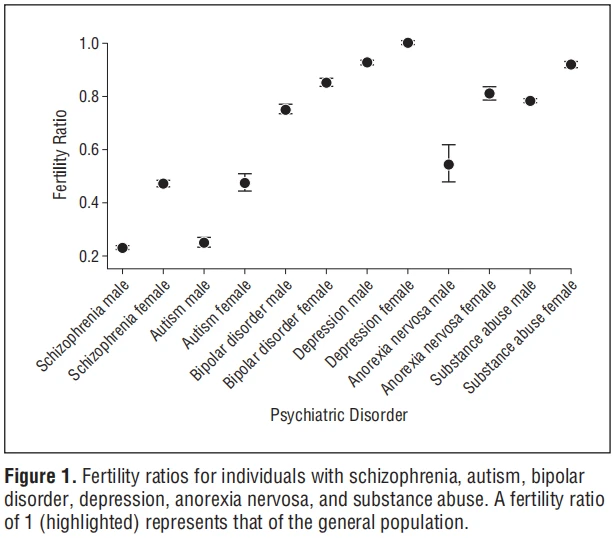

Power et al. (2013): Fecundity of Patients With Schizophrenia, Autism, Bipolar Disorder, Depression, Anorexia Nervosa, or Substance Abuse vs Their Unaffected Siblings

This study examined 2.3 million individuals in Swedish population databases. They measured the fertility rate of people with various mental disorders and compared it to the general population.

Autistic men had a fertility ratio of 0.25, meaning that autistic men had 1/4th the number of children as neurotypical men.

Autistic women had one of 0.48. Mental disorders in general didn’t appear to affect women’s reproductive rate as much.

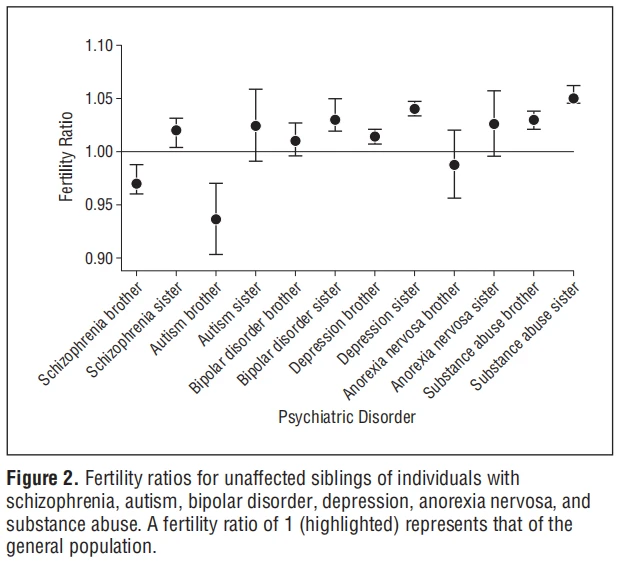

They also found that unaffected brothers of autistic individuals had a fertility ratio significantly below average, while this wasn’t true for any other group other than brothers of schizophrenics. This makes the continued presence of autism all the more mysterious.

A study based on the same Swedish population data (Nordsletten et al., 2016) with a less restrictive sample including younger subjects and presumably a higher proportion of higher-functioning autistic people, since that tends to be the trend as diagnosis rates increase, found similar results for the proportion who’d ever reproduced, with an OR of .22 for autistic men vs. a population sample matched on age etc., and an OR for women of .36.

They also found a high degree of assortative mating between among autistic men and women. Of course the skewed sex ratio means this isn’t a viable strategy for most autistic men though.

Stoddart et al. (2013): Diversity in Ontario’s Youth and Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorders: Complex Needs in Unprepared Systems

This study included 480 individuals (72.5% male; M age = 29.1). 50.8% were higher-functioning, 23.8% ‘had autism’, 15.6% had PDD (pervasive developmental disorder), and 14.8% were diagnosed with an intellectual disability.

These are the results most pertinent to the current topic:

Marital status of the individuals with ASD was reported: 415 (86.5%) were single, 43 (9%) were married, 11 (2.3%) were separated or divorced, and 10 (2%) were living common-law. Respondents reported that 10% had biological children.

Also, 32.1% reported that they’d had a romantic or intimate relationship in the past.

Del Giudice et al. (2014): Autistic-like and Schizotypal Traits in a Life History Perspective: Diametrical Associations with Impulsivity, Sensation Seeking, and Sociosexual Behavior

152 participants (50.7% male; M age = 22.7) filled out the AQ questionnaire & the MSOI again (among others).

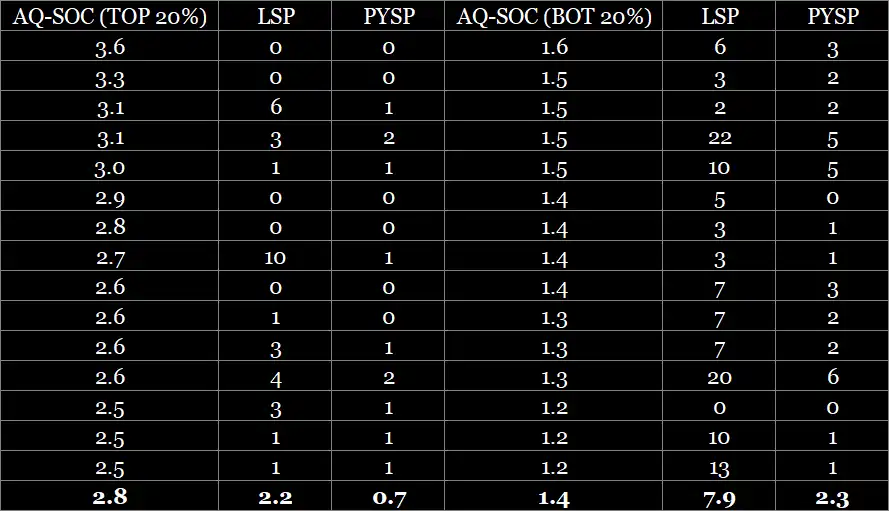

While the study may be interesting, I downloaded the raw data to produce a table more relevant to this analysis. I arranged the men with the top and bottom 15 (roughly 20%) scores on the social skills subscale of the AQ, along with the number of sex partners they had in their lifetimes and in the past year.

Among the men with the highest AQ scores, they had an average of 2.2 lifetime sex partners and 0.7 in the past year. Among the men with the lowest AQ scores however, they had an average of 7.9 lifetime sex partners and 2.3 in the past year, about 3.5x as many. Two-sample t-tests revealed highly statistically significant differences.

We also find that the men with the highest two scores, so the most likely to be clinically autistic, were virgins, and 5 men in the top 20% of AQ were virgins compared to 1 in the bottom.

Ponzi et al. (2016): Autistic-Like Traits, Sociosexuality, and Hormonal Responses to Socially Stressful and Sexually Arousing Stimuli in Male College Students

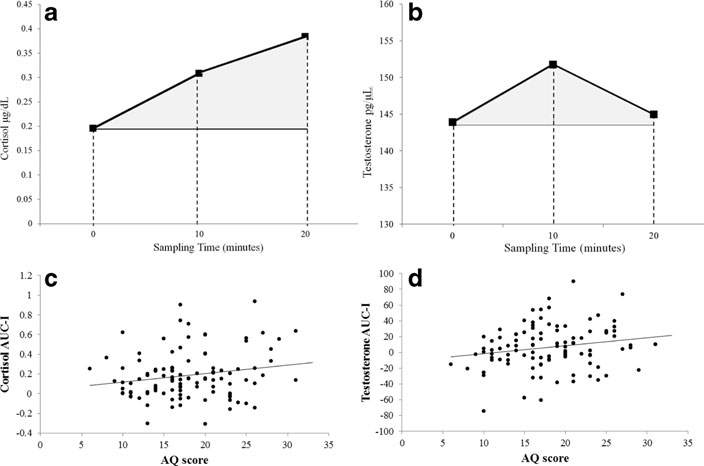

This study set out to test the hypothesis that autistic-like traits were associated with restricted sociosexuality, and investigated the role of stress and sex hormones as potential physiological mechanisms underlying the association.

They hypothesized that individuals high in autistic traits may find it stressful to interact with sexually attractive strangers due to poor social and communicative skills, and that elevation of their stress hormones during these interactions may impair their motivation or ability to engage in courtship behaviour or complete sexual interactions.

107 heterosexual male college students were assessed with the AQ and the multidimensional sociosexual inventory. They also underwent a ‘trier social stress’ test to study hormonal responses to mild psychosocial stress, and the sexual arousal test, whereby participants watch a 12 minute video clip with explicit erotic content. Before and after the test they were asked to provide saliva samples.

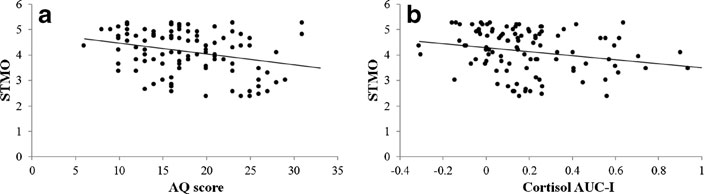

This study did find a significantly lower short-term mating orientation among those with higher AQ scores, correlating at -.27.

AQ correlated with past sexual experience at -.38, and number of lifetime sex partners at -.39.

Long-term mating orientation actually also negatively correlated at -.16, but didn’t quite reach significance.

They suggest that it’s possible that individuals with higher autistic-like traits show an aversion toward short-term mating strategies due to their previous behavioural experiences and their outcomes (e.g., having been frequently rejected by potential short-term mating partners), but that this doesn’t necessarily shift their preferences the other way toward a higher long-term mating orientation as a result.

In regards to hormones, they found that for the social stress test, while the difference between the post-task peak and baseline cortisol wasn’t significantly correlated with AQ, the overall amount of cortisol produced in response to the test after controlling for the baselines was predicted by AQ.

For the sexual arousal test, AQ significantly correlated with delta cortisol and with the AUC-I, meaning higher AQ predicted a greater increase in cortisol relative to baseline, and more production of cortisol during the test.

There was also a significant interaction between AQ and temporal changes in testosterone, suggesting that changes in testosterone between baseline and post-task were moderated by AQ. There was also a positive correlation between AQ and delta testosterone which approached statistical significance.

These results were contrary to their expectations. While men higher in autism traits found the video somewhat more stressful, they also found it more sexually arousing.

Since the testosterone reactivity to visual sexual stimuli wasn’t correlated with any sociosexual measures though, they say the study provides no hint that physiological sexual arousability may be an important mechanism underlying the association between autistic-like traits and sociosexuality.

Finally, they found that while the analysis using the delta cortisol didn’t produce statistically significant results, the analysis with the AUC-I did. The overall model testing the effect of AQ and AUC-I on Short-Term Mating Orientation was significant, and the indirect effect was too, suggesting higher cortisol secretion in response to psychosocial stress mediates the association between high AQ and low STMO.

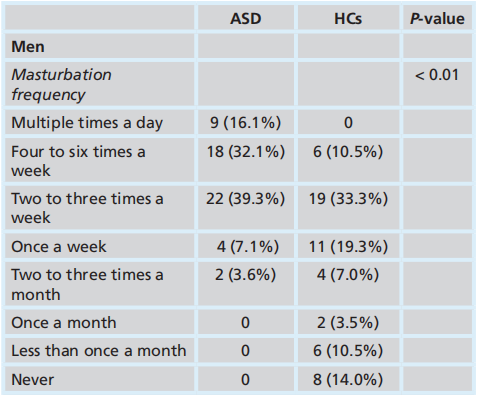

Schöttle et al. (2017): Sexuality in autism: hypersexual and paraphilic behavior in women and men with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder

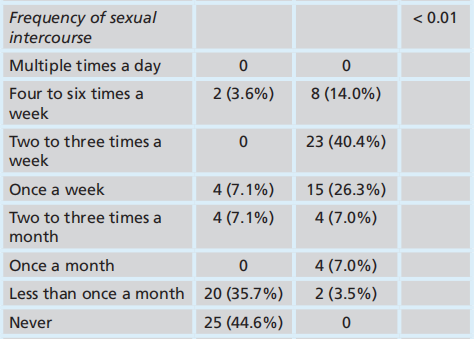

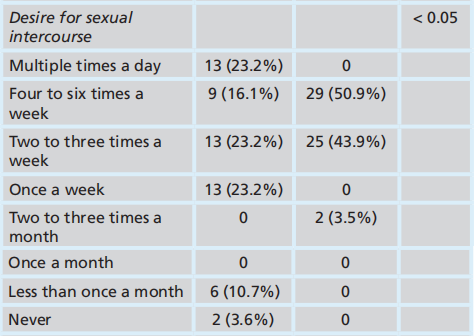

This study looked at 96 subjects with high-functioning autism (58.3% male; M age = 39.2) and 96 neurotypicals (59.4% male; M age = 37.9).

Significantly more autistic women (46.2%) than men (16.1%) were currently in a relationship, compared to 79.5% of NT women and 82.4% of NT men. 14.3% of the autistic men compared to 27.5% of the autistic women had children, but this difference wasn’t significant.

Autistic men masturbated significantly more than NT men.

On the other hand, NT men had much more actual sex. While 14% of NT men had sex 4-6x a week and 40.4% 2-3x a week, 3.6% of autistic men had sex 4-6x a week and none 2-3x a week. While 35.7% of autistic men had sex less than once a month (which could mean as little as once, period) and 44.6% were virgins, only 3.5% of NT men had sex as little as less than once a month, and none remained virgins.

These discrepancies are despite the fact that autistic men reporting high sexual desire, though it was also more heterogeneous, with more reporting higher and lower levels. Still, only 3.6% reported no sexual desire whatsoever.

While 50% of autistic women were virgins compared to 0 NT women, and 27.5% had sex less than once a month compared to 0 NT women, 42.5% of autistic women reported being asexual, and 15% desired sex less than once a month, so their sexual activity was much more in line with their desired amount.

Many more autistic men (30.4%) met the cut-off point for ‘hypersexuality’ than NT men (3.5%), including some rather disturbing results which need not be discussed here.

Strunz et al. (2017): Romantic Relationships and Relationship Satisfaction Among Adults With Asperger Syndrome and High-Functioning Autism

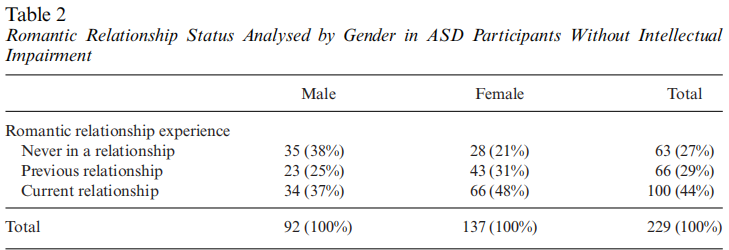

229 high-functioning autistic participants (40% male; M age = 35) answered a number of self-report questionnaires relating to relationships.

They found a significant gender difference whereby men (38%) were more likely to have never had any relationship experience relative to women (21%). 37% of the men and 48% of the women were currently in a relationship.

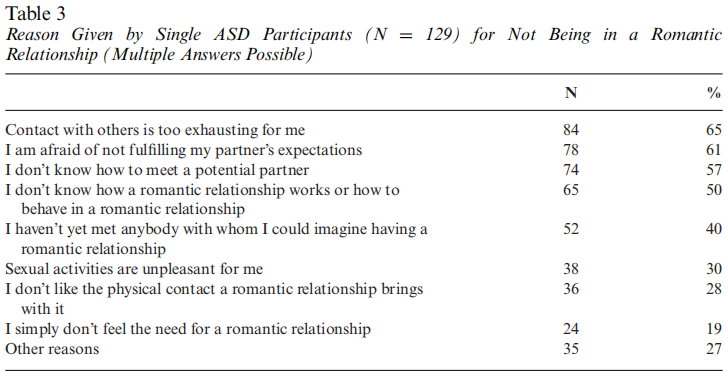

Only 17 (13%) of the 129 participants not currently in a relationship (7% of the total sample) had no desire to be in one. Men also had a significantly greater desire to be in a relationship, and were more distressed about not being in one.

Common reasons given for not being in a relationship were: “Contact with others is too exhausting for me”, “I am afraid of not fulfilling my partner’s expectations”, “I don’t know how to meet a potential partner”, and “I don’t know how a romantic relationship works or how to behave in a romantic relationship”.

They found that participants whose partners were also on the spectrum (20% of the people in relationships) had higher relationship satisfaction.

Farley et al. (2018): Mid-Life Social Outcomes for a Population-Based Sample of Adults with ASD

A stat I’ve seen thrown around is that only 5% of autistic people get married. It comes from this study of 169 (76% male; M age = 35.5) people, excluding 7 siblings who were removed, who were among 489 people originally surveyed in the 80s and then recontacted between 2007-2012.

However it’s important to realize that 77% of this sample had an intellectual disability, and were probably barely aware of the concept of marriage, making it unwise to apply this rate to the high-functioning population. Indeed, most informants of the participants said they believed their adult child didn’t want a relationship.

Still, even if all the ever-married people were above the 70 IQ cutoff for intellectual disability, that’d translate to an ever-married rate of 20.5%, still far below that of the general population’s.

They also found that about 75% had no experience with dating, 13% had dated only in a group setting, 5% had dated only in a single couple arrangement, and 6% had dated in both. Most of the 25% who had relationship experience had only had 1 or 2 relationships, while four had 3-6 (each lasting less than 3 years), and one had up to 20.

There was wide variance in relationship duration, with most lasting less than 6 months, five lasting 6 months to 2 years, another five lasting 2-3 years, and six lasted at least 10 years.

Pecora et al. (2019): Characterising the Sexuality and Sexual Experiences of Autistic Females

232 high-functioning autistic subjects (41.4% male; M age = 25.1) and 227 NTs (29.1% male; M age = 22.2) participated in this study.

Very high rates of non-heterosexuality were found across the board, especially among autistic women, where only 31.1% reported being heterosexual. I couldn’t find anything relating to the sample collecting method that’d explain this, other than the fact that many participants were recruited online, including from support forums.

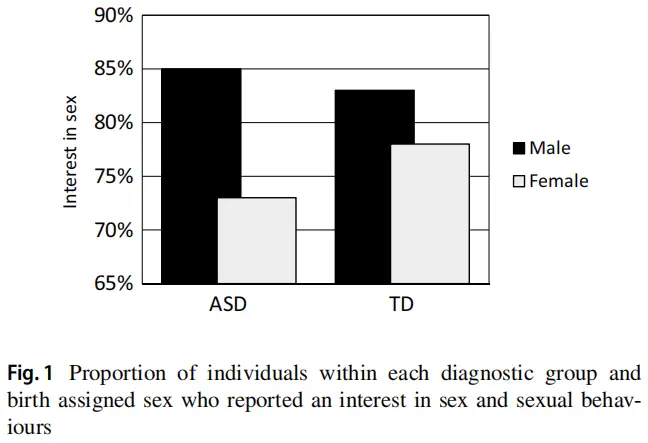

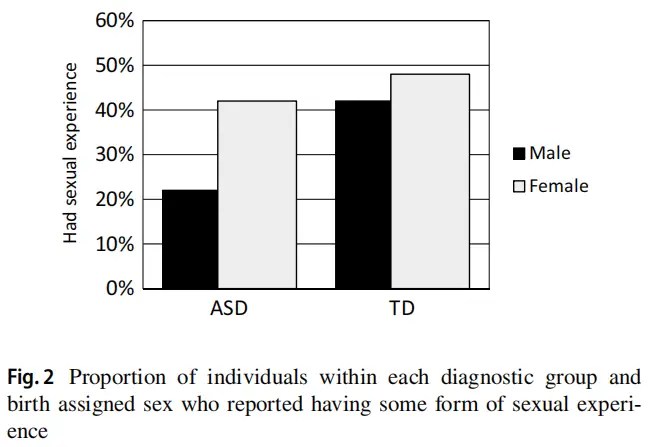

Autistic men reported significantly more sexual interest than autistic women.

Despite this, autistic men reported significantly less sexual experience than any other group. This is despite the autistic sample being older on average as well. The other groups didn’t significantly differ from each other.

Joyal et al. (2021): Sexual Knowledge, Desires, and Experience of Adolescents and Young Adults With an Autism Spectrum Disorder: An Exploratory Study

68 autistic (41 male, mean age: 19.4; 27 female, M age = 19.7) and 104 NT subjects (29 male, M age = 18.4; 75 female, M age = 19.1) participated in the study.

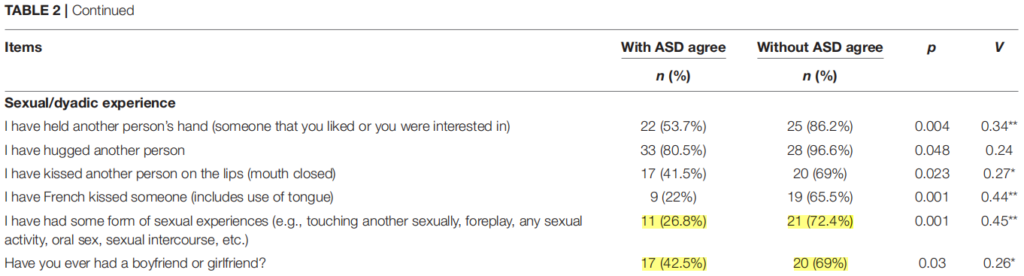

Significant differences were found between autistic and NT males, with 26.8% of autistic males and 72.4% of NT males having had some form of sexual experiences and 42.5% of autistic males and 69% of NT males having had relationship experience (despite autistic males having an extra year on NT males on average, which is a big difference at those ages).

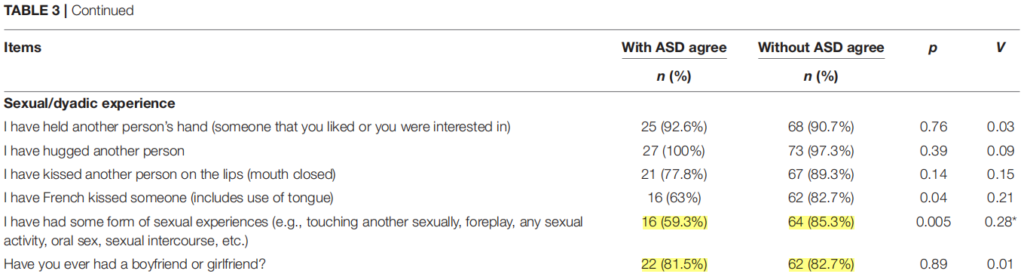

When it came to ASD and NT females however, while significant less ASD females (59.3%) than NT females (85.3%) had some form of sexual experience, there wasn’t a difference when it came to relationship experience.

Less autistic (75.6%) than NT (93.1%) males believed that being in a long-term relationship in the future is important or said they would like to have a boyfriend or girlfriend in the near future (70.7% vs. 86.2%), but the differences weren’t quite statistically significant. To be fair though, a significantly lower percentage of autistic males in this sample (61%) said they’d like to have sex with others than NT males (96.6%), and other similar things relating to sex, including porn usage.

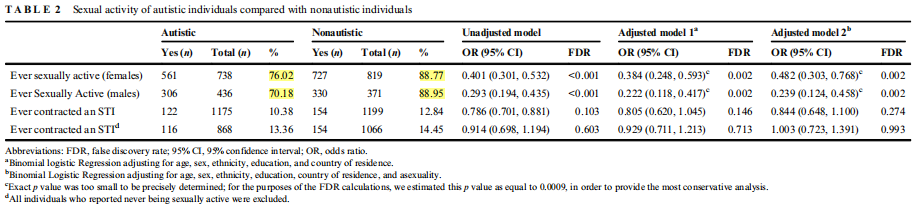

Weir et al. (2021): The sexual health, orientation, and activity of autistic adolescents and adults

1,183 autistic (36.9% male; M age = 41) and 1,203 NT (31.4% male; M age = 41.9) subjects participated in this study.

70.2% of autistic males and 76% of autistic females stated ever having been sexually active, compared to 88.8% of NT females and 89% of NT males.

A virginity rate of 11% for NTs might seem high for a mean age around 42, but the ages ranged widely from 16-90, with 1/4th of the sample being under 30. So autistic men had a 3x higher chance of being a virgin. Still, the majority of autistic men eventually get laid at least once, so it looks like it’s not completely over. It’s probably worth mentioning that 5% of autistic males and 13% of autistic females reported being asexual. Only 1.5% of NTs were asexual.

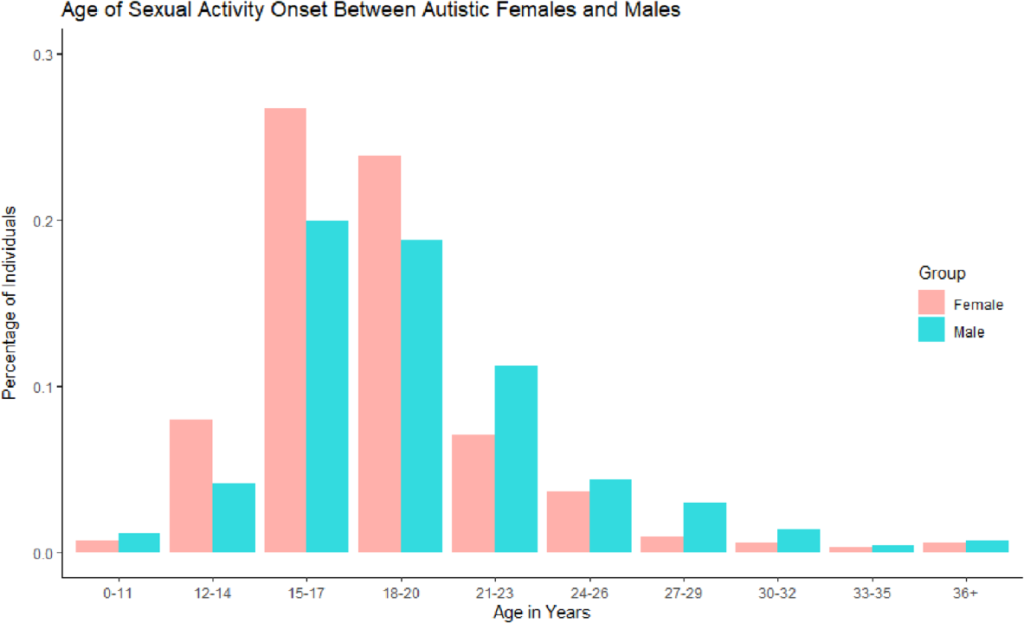

Of those who’d had sex, autistic females (mean: 18.02) also had an earlier sexual onset than autistic males (mean: 19.44). This isn’t the case for NTs however, for whom the mean age is around 17 for both genders.

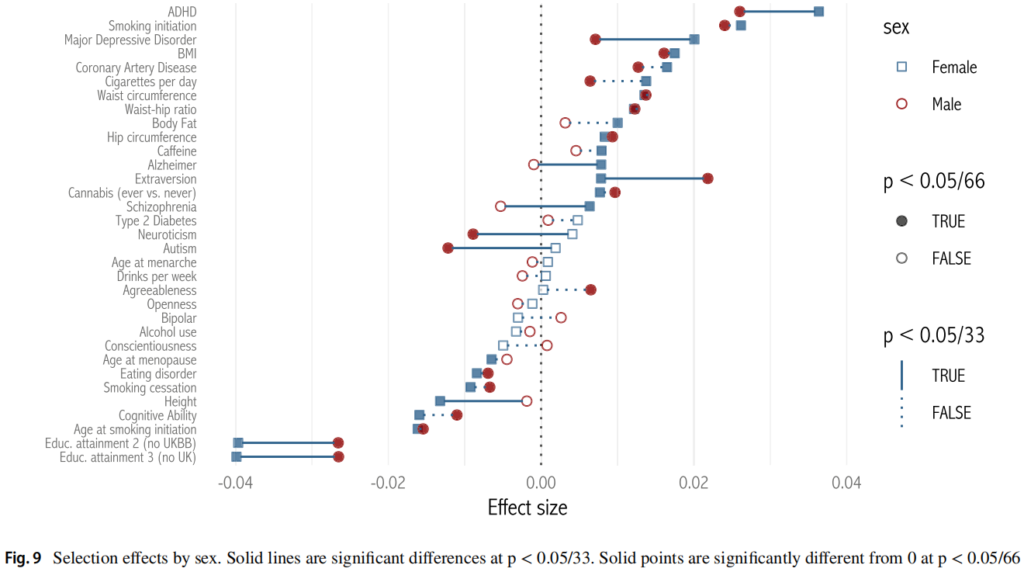

Hugh-Jones & Abdellaoui (2022): Human Capital Mediates Natural Selection in Contemporary Humans

This study analyzed polygenic risk scores for various traits using data from the UK biobank to determine which ones were being selected for or against. As we see from this chart, it’s not looking too good for autistic males:

On the other hand, autistic females don’t appear to be affected. On a similar note, we also see extraversion being selected for (more so in men), and neuroticism selected against but only in men. Perhaps contrary to black pill assumptions, height is not being positively selected in men. BMI however is.

Prevalence Among Incels

With all this in mind, we’d expect autism to be overrepresented in the incel community, but by just how much exactly? Let’s find out.

According to this article:

One large incel forum conducts periodic polls of its members. In a poll this past March, 71.5 per cent said they were on the autism spectrum.

In a poll on incels.co (ADL, 2020) which received 666 responses, 40% stated that ‘autism or similar conditions’ were a factor that they believed was significantly preventing them from finding a partner.

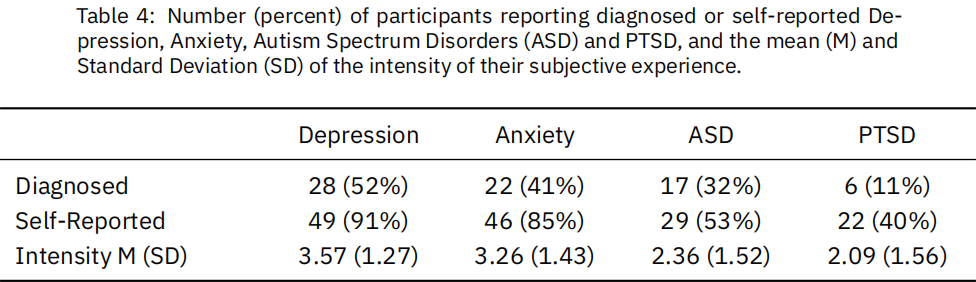

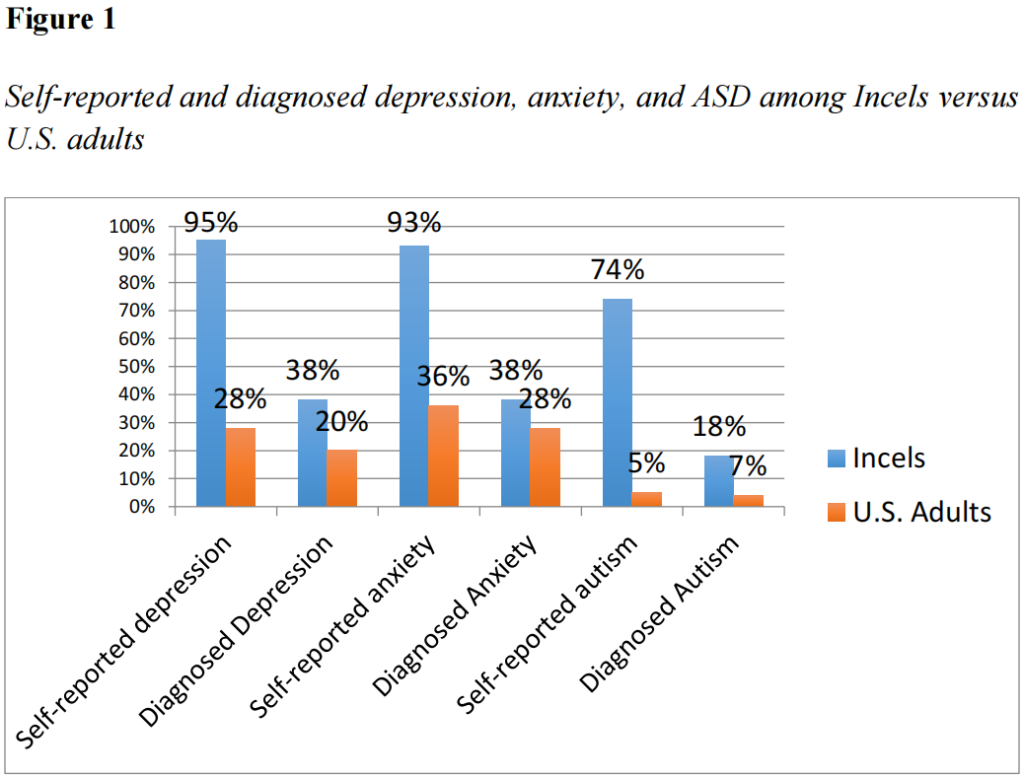

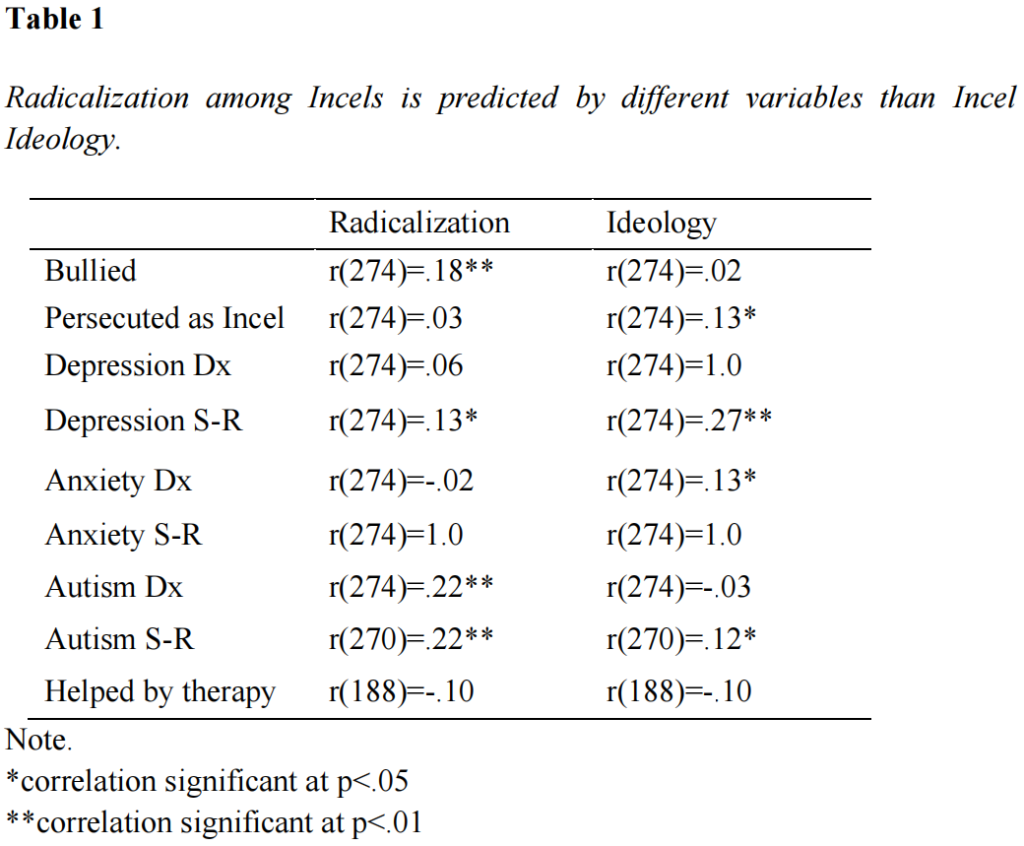

Moskalenko et al. (2022): Incel Ideology, Radicalization and Mental Health: A Survey Study

The researchers surveyed 54 self-identified Incels, and found a diagnosed autism rate of 32%, and a self-reported rate of 53%.

Moskalenko et al. (2022): Predictors of Radical Intentions among Incels: A Survey of 54 Self-identified Incels

In another survey, they found among 274 self-identified Incels a lower diagnosis rate of 18%, but a higher self-reported rate of 74%.

I’m not sure I agree however with how they determined the benchmark prevalence rate of 7%. They used the 3.6% rate for boys from the CDC (apparently it’s 4.3% now) and then added the undiagnosed rate which is supposedly 25% higher onto it. The underdiagnosis rate would likely be a lot lower among these recently diagnosed children (if anything the opposite problem exists). To be consistent you’d also need to apply this to the Incel group, meaning the actual autism rate among them would also be a lot higher. Either way, it’s a large overrepresentation.

Autism also appeared to correlate with radicalization, which could be related to autistic people’s supposed tendency towards ‘black-and-white’ thought patterns.

Of course saying you have it isn’t necessarily the same as having it, but regardless, it shows how prevalent social difficulties are within this group.

In addition to the fact that autistic men often struggle with dating, Incel ideology probably appeals to them for other reasons such as providing a sense of belonging, and the logical framework that it may seem to provide could appeal to the ‘rule based thinking’ that autistic people often exhibit.

Another thing to consider is the overrepresentation or really ubiquitous presence of autism among the notorious incel mass killers. This probably deserves its own post however.

Why?

So we know that autism is highly connected to sexual and romantic difficulties, but why is this exactly?

It shouldn’t really be surprising that a condition that causes social deficits should affect not just one’s ability to form and maintain friendships but also romantic relationships, after all most relationships begin as platonic friendships (Stinson et al., 2022).

Stokes et al. (2007) found that of the variables they analyzed, level of social functioning was the only significant predictor of romantic functioning in autistic adolescents and adults, contributing 53% of the variance.

Having fewer friendships probably further stunts social skills as socialization with peers is an important component of social development. It also means less social opportunities to meet women, and since women are probably especially concerned about ‘social proof’, being a loner is another red flag working against autistic men.

Many traits associated with autism have the potential to create difficulties with dating.

Nonverbal communication for instance is hugely important, especially when it comes to flirtation where there are a host of unspoken rules. Saying the right thing at the right time, with the right tone and inflection, and the right accompanying body language can feel like trying to juggle chainsaws on a tightrope.

Nonverbal immediacy behaviours and postural expansiveness have been shown to strongly predict success in speed-dating experiments, maybe even more than physical attractiveness (Houser et al., 2008; Vacharkulksemsuk et al., 2016). It was found to be mediated by perceived dominance. Think manspreading. Appearing stiff and uncomfortable on the other hand has to be a turn-off to many women. Even before opening your mouth they can probably tell something is ‘off’ about you.

The tendency to avoid eye contact (or sometimes gaze too intensely), struggling to understand social cues, trouble interpreting facial expressions and expressing emotions, atypical speech prosody (e.g. speaking in a monotone), sensory sensitivity creating issues around touch would all make it harder to connect and be intimate with people.

The bluntness and absence of a social filter has the potential to cause problems. If a girl asks if she looks fat in her dress for example, an autist may do the unthinkable and respond in the affirmative.

Many autistic people are prone to going on monologues about their ‘special interests’, and due to impaired theory of mind aren’t necessarily able to tell that the other person isn’t interested.

Autistic people often also have comorbid mental issues such as anxiety, social phobia, and depression (Hollocks et al., 2019). Part of this is probably a result of repeated social failures and negative feedback due to their awkward behaviour gradually chipping away at their self-esteem.

Since traditional gender roles surrounding date initiation still persist and the vast majority are initiated by men (Kendrick & Kepple, 2022), difficulty initiating and maintaining conversations is obviously going to be a big barrier. Another problem to consider is that in the event that a woman is interested, the autistic man may fail to pick up the signals and thus be unaware of the best opportunities to approach.

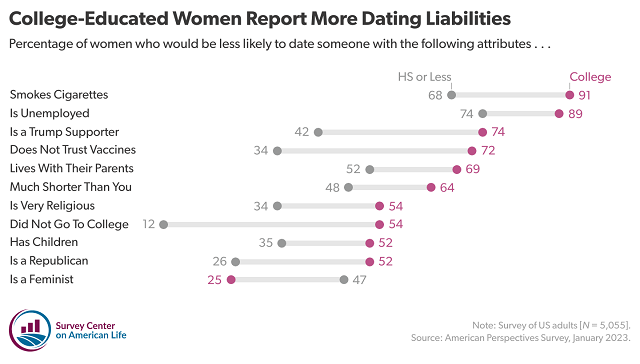

High-functioning autistic people have highly disproportionate unemployment rates despite higher than average educational attainment (Espelöer et al., 2023).

Most women are of course a lot less likely to consider dating a man if he is unemployed (or lives with their parents):

In terms of sex, most of it happens within the context of relationships, and unless a girl is going to spontaneously pull your pants down on the spot you have to at least be able to talk to them first.

Does It Affect Men Worse?

While it’s by no means a competition, most of the data seems to indicate that the effect of autism impedes men’s romantic functioning to a greater degree than women’s. This is also a sentiment I’ve seen expressed a fair amount by autistic men.

I’ve already mentioned a couple of possible reasons for this. Men remain the primary initiators. Suffering from social anxiety and being more introverted and neurotic (Austin, 2005; Wakabayashi et al., 2006) as well as lacking the social aptitude to properly carry a conversation is going to be much more of a hindrance when it comes to fulfilling this role.

Women likely have a higher demand for social proof. Since women have historically relied upon men for survival and men’s capacity to cooperate and form coalitions with others was vital in matters of hunting and violent conflict, a man’s position on the social hierarchy has more salience.

It’s arguable that autistic social traits may even be desirable in women to an extent. Wu et al. (2016) for instance found that a G allele associated with social dominance positively predicted men’s speed-dating success but negatively predicted women’s. On the other hand, a G allele associated with social submissiveness negatively predicted men’s success but positively predicted women’s. While being shy and timid is typically perceived as a sign of weakness in men, this isn’t the case for women.

Autistic females have also been observed to be more likely to ‘mask’ their symptoms than their male counterparts (Wood-Downie et al., 2021).

Due to women having a higher minimum investment in reproduction they’ll be more vigilant in general about filtering out mentally deviant individuals who may not make great parents and who may pass the underlying genes on to their offspring.

While it may not be as detrimental to their ability to find a partner, it may bring a different kind of problem such as their social naivety making them enticing targets for men who are looking to use them for sex or abuse them. Pecora et al. (2019) for instance found that significantly more autistic than NT women reported being the subject of an unwanted sexual experience or advance.

Is It Just A Proxy For Ugliness?

Many Incels like to reduce everything to discrimination on the basis of physical traits, and autism is no exception.

A commonly advanced claim is that autism is simply the result of social rejection stemming from one’s physical shortcomings, preventing normal social development from occurring.

It shares some resemblance with the ‘refrigerator mother theory‘, which maintained that maternal neglect was the cause for children’s autistic traits.

It is well-established by now however that autism is largely genetic in origin. Autism is polygenic, meaning it’s not as simple as tracking down a single gene, but without getting too much into the weeds genome sequencing has revealed a large number of genes that likely contribute to the condition (Cirnigliaro et al., 2023).

Tick et al. (2016) in a meta-analysis of twin studies found heritability estimates between 64-91%, and found a near perfect intrapair correlation of .98 in monozygotic twins, and .53-.67 in dizygotic twins. I guess the identical twins, looking the same and all, must have just been equally victimized by lookism.

Hoekstra et al. (2007) found that autistic traits distributed across the general population also show a high degree of heritability (57%).

Numerous neuroanatomical differences between autistic and NT brains have also been observed (Donovan & Basson, 2017). One of these is early brain overgrowth. Courchesne et al. (2011) found that children with autism had 67% more neurons in the prefrontal cortex than did NT children.

Symptoms can often be detected early on before the child has had a chance to interact with peers, for instance Nyström et al. (2019) found using eye-tracking technology that infants who had a reduced tendency to initiate joint attention episodes had a much greater chance of being diagnosed with autism a few years down the line.

Finally, it’s hard to imagine how this theory would account for symptoms unrelated to social communication impairments such as sensory sensitivities or restrictive and repetitive behaviours.

Others may argue that autism is inherently linked to facial abnormalities which is the real reason for its negative association with men’s dating success.

While it’s often labeled an ‘invisible disability’, it may be the case that there are subtle facial deviations from the norm.

Aldridge et al. (2011) for example found a “distinctive facial phenotype characterized by an increased breadth of the mouth, orbits and upper face, combined with a flattened nasal bridge and reduced height of the philtrum and maxillary region”.

They also discovered two apparent subgroups with distinct phenotypes, one with decreased height of the facial midline, increased breadth of the mouth, and increased length and height of the chin, and another with increased breadth of the upper face and decreased height of the philtrum. The first subgroup was more severely autistic, with only 8% diagnosed with Asperger syndrome compared to 60% in the second, and with 50% compared to 20% in the second subgroup having a below 70 full-scale IQ.

It may be the case that it’s more noticeable on the lower-functioning end of the spectrum. It was reported at the 2011 International Meeting for Autism Research that:

The vast majority of cases [in that study] show very subtle facial differences … Those who have more dysmorphology tend to have more problems and be more severely affected

Spectrum News

Links et al. (1980) found that the autistic children with the most anomalies had lower IQs and spent more time in the hospital.

To the extent that fluctuating asymmetry is connected to deleterious mutations, it seems like an excess of de novo loss-of-function mutations may be limited to autistic subjects with a below average IQ (Samocha et al., 2014).

Findings have also generally been rather inconsistent when it comes to facial dysmorphology, with the exception of facial asymmetry which seems to be consistently replicable (Boutrus et al., 2017).

Boutrus et al. (2021) failed to find a significant association between AQ and facial asymmetry, with the exception of horizontal asymmetry which also failed to reach significance after controlling for certain demographic characteristics, so it was suggested then that this association may be limited to the clinical population. Boutrus et al. (2019) found that facial asymmetry was especially pronounced the more severe the symptomology.

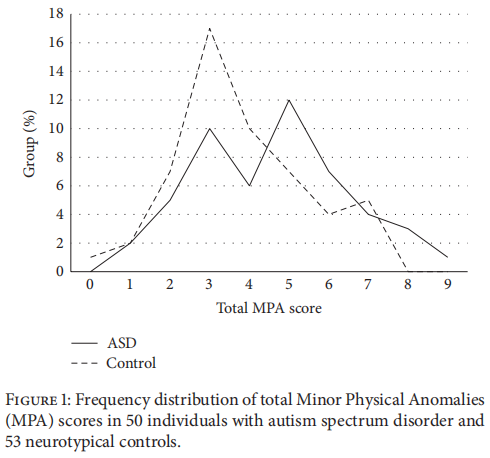

This is a chart from Manouilenko et al. (2014) showing the distribution of MPAs (minor physical anomalies) between autistic subjects and NT controls. As you can see, very few NTs are physically ‘flawless’ either, though the autistic group did have higher rates on average.

They also found that in the high-MPA group, MPAs correlated with lower overall functioning and with severity of psychiatric symptoms.

Myers et al. (2017) found that the association between ASD and MPAs became nonsignificant after controlling for IQ, though the association between autistic traits among the entire sample and MPAs remained significant.

The most common MPAs in participants with ASD included overweight (39%), hypermobility (36%), pes planus (29%), straight eyebrows (29%), vision impairment (25%; 29% of these with corrective lenses), arachnodactyly/long toes (25%), long eyelashes (21%), and microtia (21%). I’m not sure that these traits would be considered a ‘death sentence’.

It’s not obvious that any of this would have a serious impact on attractiveness or mating outcomes regardless.

The research on facial symmetry’s effect on attractiveness is a mixed bag. Noor & Evans (2003) for instance found that while it was associated with ratings of neuroticism, agreeableness, and conscientiousness, it had no relation to attractiveness ratings.

In a meta-analysis, Van Dongen & Gangestad (2011) concluded that the effects of fluctuating asymmetry on facial attractiveness is ‘almost certainly very weak’, and the effect size very likely less than .1. At the same time they did find a ‘robust’ effect on men’s number of sex partners (though still weak).

Kordsmeyer & Penke (2017) on the other hand, in a sample of 141 males with a mean age around 24, failed to find a significant association between aggregate MPAs, bodily fluctuating asymmetry, or dermatogylphic fluctuating asymmetry in palmar atd angles and mating success outcome variables.

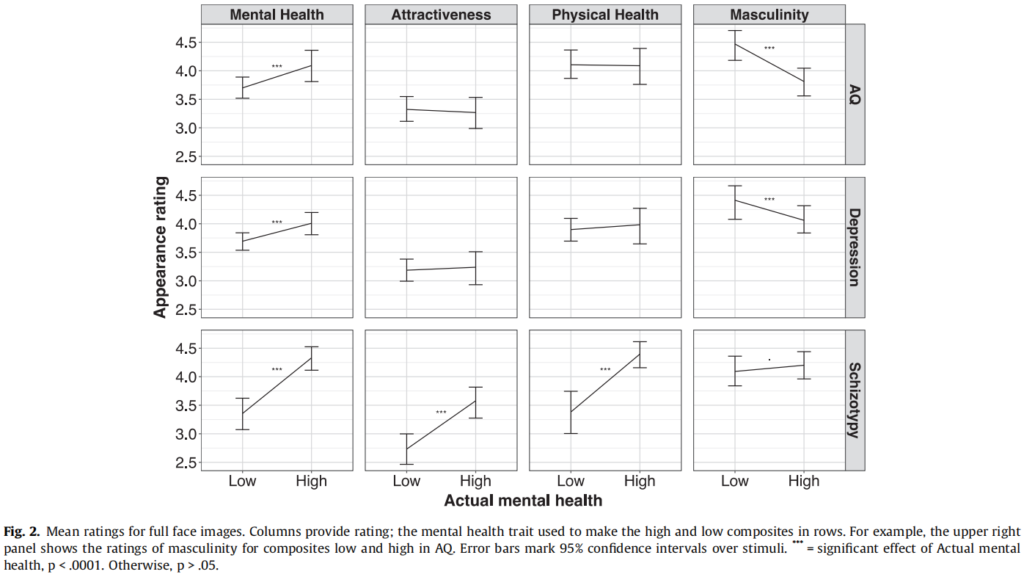

Ward & Scott (2018) found no association between autistic traits and facial attractiveness ratings of composite images made from men scoring high and low on three mental health inventories including the AQ. They were also rated significantly higher in masculinity (facial masculinity has a non-linear association with men’s attractiveness), but somewhat lower in mental health.

So while there may be subtle facial cues which allow mental health to be to some extent detectable, this doesn’t seem to translate to lower attractiveness (except in the case of schizocels apparently).

To the extent that autistic people are less visually attractive, it could also be due to spending less effort on grooming, self-care, or fashion.

Conclusion

It looks like social skills do matter after all. Of course to most people this won’t be too shocking, but despite the highly disproportionate presence of autism in the Incel community, they ironically frequently deny its impact for the simple fact that it isn’t a physical trait. One way they try and get around it is to simply reduce autism and its consequences to physical inadequacy, but we’ve seen why this doesn’t hold up.

Another common rejoinder is that ‘chad’ could apparently get away with being socially inept, he’ll have women throwing themselves at him and perceiving everything he does as cute so therefore it doesn’t really matter. Even assuming this were the case, I shouldn’t have to explain why this is a non-sequitur. It doesn’t suddenly not matter for the majority simply because a minority can overcome it by heavily compensating in another area, if anything the need to do this would just prove the point.

We’ve also seen that the asexuality stereotype is mostly bunk. Although there does seem to be a higher rate of it (assuming it’s not a cope), especially among women, the vast majority of autistic men are interested in relationships and are at least as horny as NT men.

It’s hard to think of an autistic trait which wouldn’t cause problems, and men’s role as initiator screws over autistic men especially hard. Moreover, autistic people tend to be rejected and victimized by peers, causing low self-esteem and social withdrawal. One might even be tempted to view this as a manifestation of intrasexual competition. But I guess nature lets it remain in the gene pool somehow for those rare events in which it leads to a great innovation.

Unfortunately, it becomes exponentially harder the more you fall behind and lack the experience of your peers. Lagging behind socially means less of a foundation for more complex relationships, and if you don’t get your feet off the ground reasonably early it doesn’t take too long before you go from a perhaps forgivable level of awkwardness to ‘creepy’.

The internet probably hasn’t helped things either. Autistic traits have been shown to correlate with being ‘terminally online’ (Romano et al., 2014). Escaping from the real world means not leaving your comfort zone and ultimately stagnation. Not to mention the allure of certain subcultures online such as one mentioned here which can only alienate you further.

There’s been a lot of talk about how the #MeToo movement has ruined the dating landscape. I’m not sure exactly how real the threat of persecution is or how much is fear mongering or a rationalization of fear, but to the extent that it is real it hurts nobody more than autistic men.

A story made the rounds a few years ago about a boy who approached a girl by touching her arm. He was convicted with sexual assault, issued a hefty fine, and sentenced to 200 hours of community service.

He said he was ‘shy, anxious, and awkward’ and ‘the words didn’t come out’. Prior to the event he had googled ‘how to make a friend’. It doesn’t seem like a stretch to assume he was on the spectrum, which would have made him less aware of personal boundaries.

Social mishaps can apparently be highly dangerous. A single fumbled interaction has the potential to spiral out of control and ruin your reputation. Of course this case made headlines for a reason – it’s an extreme example, but it’s not an encouraging precedent.

‘Just be yourself’ is indeed unlikely to be helpful advice, because that is sadly where the problem arises to begin with. Not necessarily because oneself is inherently bad, but more ‘not highly compatible with wider society’.

A common ‘solution’ proposed is that autistic men simply find autistic waifus. As I said, the gender ratio makes this unfeasible. The autistic chads are able to monopolize the autism dating market. Autistic women are also less desperate.

Of course the takeaway isn’t necessarily to just throw in the towel if you’re on the spectrum. How much you can change, need to change, and are willing to change will depend on the individual however. Let Christine Chandler be your motivation (to not end up like that).

To conclusively answer the question is autism the ‘real’ black pill, we’d have to I suppose compare the outcomes to those of men in the bottom 5% or so of looks/height, or the top 20% or so in AQ scores to the bottom 20% in looks/height. That is outside the scope of this post however, but see the post on height and sexual success for an idea of how it compares to that.

References

Cederlund, M., Hagberg, B., Billstedt, E., Gillberg, I. C., & Gillberg, C. (2008). Asperger syndrome and autism: a comparative longitudinal follow-up study more than 5 years after original diagnosis. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 38(1), 72–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-007-0364-6

Hofvander, B., Delorme, R., Chaste, P., Nydén, A., Wentz, E., Ståhlberg, O., Herbrecht, E., Stopin, A., Anckarsäter, H., Gillberg, C., Råstam, M., & Leboyer, M. (2009). Psychiatric and psychosocial problems in adults with normal-intelligence autism spectrum disorders. BMC psychiatry, 9, 35. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-9-35

Del Giudice, M., Angeleri, R., Brizio, A., & Elena, M. R. (2010). The evolution of autistic-like and schizotypal traits: a sexual selection hypothesis. Frontiers in psychology, 1, 41. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2010.00041

Cottenceau, H., Roux, S., Blanc, R., Lenoir, P., Bonnet-Brilhault, F., & Barthélémy, C. (2012). Quality of life of adolescents with autism spectrum disorders: comparison to adolescents with diabetes. European child & adolescent psychiatry, 21(5), 289–296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-012-0263-z

Power, R., Kyaga, S., Uher, R., MacCabe, J., Långström, N., Landen, M., McGuffin, P., Lewis, C. M., Lichtenstein, P., & Svensson, A. C. (2013). Fecundity of Patients With Schizophrenia, Autism, Bipolar Disorder, Depression, Anorexia Nervosa, or Substance Abuse vs Their Unaffected Siblings. JAMA Psychiatry, 70(1), 22-30. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.268

Nordsletten, A. E., Larsson, H., Crowley, J. J., Almqvist, C., Lichtenstein, P., & Mataix-Cols, D. (2016). Patterns of Nonrandom Mating Within and Across 11 Major Psychiatric Disorders. JAMA psychiatry, 73(4), 354–361. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.3192

Stoddart, Kevin & Burke, Lillian & Muskat, Barbara & Manett, Jason & Southey, Sarah & Accardi, Claudia & Riosa, Priscilla & Bradley, Elspeth. (2013). Diversity in Ontario’s Youth and Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorders: Complex Needs in Unprepared Systems. 10.13140/2.1.3994.0165.

Del Giudice, M., Klimczuk, A. C. E., Traficonte, D. M., & Maestripieri, D. (2014). Autistic-like and schizotypal traits in a life history perspective: diametrical associations with impulsivity, sensation seeking, and sociosexual behavior. Evolution and Human Behavior, 35(5), 415–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2014.05.007

Ponzi, D., Henry, A., Kubicki, K., Nickels, N., Wilson, M. C., & Maestripieri, D. (2015). Autistic-Like traits, sociosexuality, and hormonal responses to socially stressful and sexually arousing stimuli in male college students. Adaptive Human Behavior and Physiology, 2(2), 150–165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40750-015-0034-4

Schöttle, D., Briken, P., Tüscher, O., & Turner, D. (2017). Sexuality in autism: hypersexual and paraphilic behavior in women and men with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 19(4), 381–393. https://doi.org/10.31887/dcns.2017.19.4/dschoettle

Strunz, S., Schermuck, C., Ballerstein, S., Ahlers, C. J., Dziobek, I., & Roepke, S. (2017). Romantic Relationships and Relationship Satisfaction Among Adults With Asperger Syndrome and High-Functioning Autism. Journal of clinical psychology, 73(1), 113–125. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22319

Farley, M., Cottle, K. J., Bilder, D., Viskochil, J., Coon, H., & McMahon, W. (2018). Mid-life social outcomes for a population-based sample of adults with ASD. Autism research : official journal of the International Society for Autism Research, 11(1), 142–152. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.1897

Pecora, L. A., Hancock, G. I., Mesibov, G. B., & Stokes, M. A. (2019). Characterising the Sexuality and Sexual Experiences of Autistic Females. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 49(12), 4834–4846. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-04204-9

Joyal, C. C., Carpentier, J., McKinnon, S., Normand, C. L., & Poulin, M. H. (2021). Sexual Knowledge, Desires, and Experience of Adolescents and Young Adults With an Autism Spectrum Disorder: An Exploratory Study. Frontiers in psychiatry, 12, 685256. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.685256

Weir, E., Allison, C., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2021). The sexual health, orientation, and activity of autistic adolescents and adults. Autism Research, 14(11), 2342–2354. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.2604

Hugh-Jones, D., & Abdellaoui, A. (2022). Human Capital Mediates Natural Selection in Contemporary Humans. Behavior genetics, 52(4-5), 205–234. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10519-022-10107-w

‘Inside the minds of incels: Experts seek to short-circuit the spiral from loneliness to loathing to violence’

https://nationalpost.com/news/inside-the-minds-of-incels-experts-seek-to-short-circuit-the-spiral-from-loneliness-to-loathing-to-violence

‘Online Poll Results Provide New Insights into Incel Community’

https://www.adl.org/resources/blog/online-poll-results-provide-new-insights-incel-community

Moskalenko, S., González, J. F., Kates, N., & Morton, J. (2022). Incel Ideology, radicalization and mental health. Journal of Intelligence, Conflict and Warfare, 4(3), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.21810/jicw.v4i3.3817

Moskalenko, S., Kates, N., González, J. F., & Bloom, M. (2022). Predictors of Radical Intentions among Incels. Journal of Online Trust and Safety, 1(3). https://doi.org/10.54501/jots.v1i3.57

Stinson, D. A., Cameron, J. J., & Hoplock, L. B. (2022). The Friends-to-Lovers Pathway to Romance: Prevalent, Preferred, and Overlooked by Science. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 13(2), 562-571. https://doi.org/10.1177/19485506211026992

Stokes, M., Newton, N., & Kaur, A. (2007). Stalking, and social and romantic functioning among adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 37(10), 1969–1986. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-006-0344-2

Houser, M. L., Horan, S. M., & Furler, L. A. (2008). Dating in the fast lane: How communication predicts speed-dating success. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 25(5), 749–768. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407508093787

Vacharkulksemsuk, T., Reit, E., Khambatta, P., Eastwick, P. W., Finkel, E. J., & Carney, D. R. (2016). Dominant, open nonverbal displays are attractive at zero-acquaintance. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113(15), 4009–4014. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1508932113

Hollocks, M. J., Lerh, J. W., Magiati, I., Meiser-Stedman, R., & Brugha, T. S. (2019). Anxiety and depression in adults with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological medicine, 49(4), 559–572. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291718002283

Kendrick, S., & Kepple, N. J. (2022). Scripting Sex in Courtship: Predicting genital contact in date outcomes. Sexuality & Culture, 26(3), 1190–1214. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-021-09938-2

Espelöer, J., Proft, J., Falter-Wagner, C. M., & Vogeley, K. (2023). Alarmingly large unemployment gap despite of above-average education in adults with ASD without intellectual disability in Germany: a cross-sectional study. European archives of psychiatry and clinical neuroscience, 273(3), 731–738. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-022-01424-6

Austin, E. J. (2005). Personality correlates of the broader autism phenotype as assessed by the Autism Spectrum Quotient (AQ). Personality and Individual Differences, 38(2), 451–460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2004.04.022

Wakabayashi, A., Baron-Cohen, S., & Wheelwright, S. (2006). Individual and gender differences in Empathizing and Systemizing: Measurement of individual differences by the Empathy Quotient (EQ) and the Systemizing Quotient (SQ). Japanese Journal of Psychology, 77(3), 271–277. https://doi.org/10.4992/jjpsy.77.271

Wood-Downie, H., Wong, B., Kovshoff, H., Mandy, W., Hull, L., & Hadwin, J. A. (2021). Sex/Gender Differences in Camouflaging in Children and Adolescents with Autism. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 51(4), 1353–1364. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04615-z

Wu, K., Chen, C., Moyzis, R. K., Greenberger, E., & Yu, Z. (2016). Gender Interacts with Opioid Receptor Polymorphism A118G and Serotonin Receptor Polymorphism -1438 A/G on Speed-Dating Success. Human nature (Hawthorne, N.Y.), 27(3), 244–260. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12110-016-9257-8

Cirnigliaro, M., Chang, T. S., Arteaga, S. A., Pérez-Cano, L., Ruzzo, E. K., Gordon, A., Bicks, L. K., Jung, J. Y., Lowe, J. K., Wall, D. P., & Geschwind, D. H. (2023). The contributions of rare inherited and polygenic risk to ASD in multiplex families. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 120(31), e2215632120. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2215632120

Tick, B., Bolton, P., Happé, F., Rutter, M., & Rijsdijk, F. (2016). Heritability of autism spectrum disorders: a meta-analysis of twin studies. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines, 57(5), 585–595. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12499

Hoekstra, R. A., Bartels, M., Verweij, C. J., & Boomsma, D. I. (2007). Heritability of autistic traits in the general population. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine, 161(4), 372–377. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.161.4.372

Donovan, A. P., & Basson, M. A. (2017). The neuroanatomy of autism – a developmental perspective. Journal of anatomy, 230(1), 4–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/joa.12542

Nyström, P., Thorup, E., Bölte, S., & Falck-Ytter, T. (2019). Joint Attention in Infancy and the Emergence of Autism. Biological psychiatry, 86(8), 631–638. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2019.05.006

Courchesne, E., Mouton, P. R., Calhoun, M. E., Semendeferi, K., Ahrens-Barbeau, C., Hallet, M. J., Barnes, C. C., & Pierce, K. (2011). Neuron number and size in prefrontal cortex of children with autism. JAMA, 306(18), 2001–2010. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2011.1638

Aldridge, K., George, I. D., Cole, K. K., Austin, J. R., Takahashi, T. N., Duan, Y., & Miles, J. H. (2011). Facial phenotypes in subgroups of prepubertal boys with autism spectrum disorders are correlated with clinical phenotypes. Molecular autism, 2(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.1186/2040-2392-2-15

Rudacille, D. “Facial features provide clue to autism severity”. Spectrum News. https://www.spectrumnews.org/news/facial-features-provide-clue-to-autism-severity/

Links, P. S., Stockwell, M., Abichandani, F., & Simeon, J. (1980). Minor physical anomalies in childhood autism. Part I. Their relationship to pre- and perinatal complications. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 10(3), 273–285. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02408286

Samocha, K. E., Robinson, E. B., Sanders, S. J., Stevens, C., Sabo, A., McGrath, L. M., Kosmicki, J. A., Rehnström, K., Mallick, S., Kirby, A., Wall, D. P., MacArthur, D. G., Gabriel, S. B., DePristo, M., Purcell, S. M., Palotie, A., Boerwinkle, E., Buxbaum, J. D., Cook, E. H., Jr, Gibbs, R. A., … Daly, M. J. (2014). A framework for the interpretation of de novo mutation in human disease. Nature genetics, 46(9), 944–950. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3050

Boutrus, M., Maybery, M. T., Alvares, G. A., Tan, D. W., Varcin, K. J., & Whitehouse, A. J. O. (2017). Investigating facial phenotype in autism spectrum conditions: The importance of a hypothesis driven approach. Autism Research, 10(12), 1910–1918. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.1824

Boutrus, M., Gilani, Z., Maybery, M. T., Alvares, G. A., Tan, D. W., Eastwood, P. R., Mian, A., & Whitehouse, A. J. O. (2021). Brief Report: Facial Asymmetry and Autistic-Like Traits in the General Population. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 51(6), 2115–2123. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04661-7

Boutrus, M., Gilani, S. Z., Alvares, G. A., Maybery, M. T., Tan, D. W., Mian, A., & Whitehouse, A. J. O. (2019). Increased facial asymmetry in autism spectrum conditions is associated with symptom presentation. Autism research : official journal of the International Society for Autism Research, 12(12), 1774–1783. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.2161

Manouilenko, I., Eriksson, J. M., Humble, M. B., & Bejerot, S. (2014). Minor physical anomalies in adults with autism spectrum disorder and healthy controls. Autism research and treatment, 2014, 743482. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/743482

Myers, L., Anderlid, B. M., Nordgren, A., Willfors, C., Kuja-Halkola, R., Tammimies, K., & Bölte, S. (2017). Minor physical anomalies in neurodevelopmental disorders: a twin study. Child and adolescent psychiatry and mental health, 11, 57. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-017-0195-y

Noor, F., & Evans, D. C. (2003). The effect of facial symmetry on perceptions of personality and attractiveness. Journal of Research in Personality, 37(4), 339–347. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0092-6566(03)00022-9

Van Dongen, S., & Gangestad, S. W. (2011). Human fluctuating asymmetry in relation to health and quality: A meta-analysis. Evolution and Human Behavior, 32(6), 380–398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2011.03.002

Kordsmeyer, T. L., & Penke, L. (2019). Effects of male testosterone and its interaction with cortisol on self- and observer-rated personality states in a competitive mating context. Journal of Research in Personality, 78, 76–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2018.11.001

Ward, R., & Scott, N. J. (2018). Cues to mental health from men’s facial appearance. Journal of Research in Personality, 75, 26–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2018.04.007

Romano, M., Truzoli, R., Osborne, L. A., & Reed, P. (2014). The relationship between autism quotient, anxiety, and internet addiction. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 8(11), 1521–1526. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2014.08.002

Gallagher, T. & Yarwood, S. (2019). ”Lonely’ student who inappropriately touched girl given 200 hours community work”. The Mirror. https://www.mirror.co.uk/news/uk-news/lonely-student-who-inappropriately-touched-20708450

Well argued.

For some reason there is a strong aversion to the concept of “mentalcels”

How about writing on the “cure” or treatment for Asperger’s Syndrome.

Wow superb blog layout How long have you been blogging for you make blogging look easy The overall look of your site is magnificent as well as the content

you are in reality a just right webmaster The site loading velocity is incredible It seems that you are doing any unique trick In addition The contents are masterwork you have performed a wonderful task on this topic

Wow wonderful blog layout How long have you been blogging for you make blogging look easy The overall look of your site is great as well as the content

It’s fucking over.

After suffering atrocities of this NT-based society for 40 years till the diagnosis (and after this I was victim of criminal activities of the system), I saw that the society is nothing else than a deadly enemy. What is this masking bringing than self-deconstruction? And for what – for this soulless NT-Demons? They don’t deserve this…

Очень стильные события индустрии.

Абсолютно все новости всемирных подуимов.

Модные дома, торговые марки, haute couture.

Приятное место для модных хайпбистов.

https://fashionsecret.ru

Great site with quality based content. You’ve done a remarkable job in discussing. Check out my website Webemail24 about Data Mining and I look forward to seeing more of your great posts.