Did 1 Man Reproduce For Every 17 Women?

Perhaps the central pillar of the argument that polygamy is the ‘natural’ human mating system which societies default to in the absence of ‘enforced monogamy’ is the idea that far more women than men were reproductively successful throughout history.

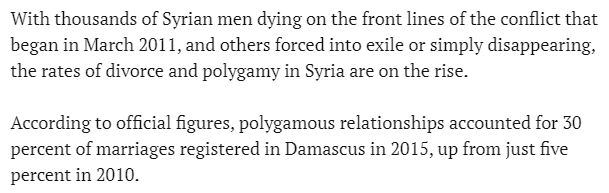

A screencap of this article in support of this notion has been widely disseminated:

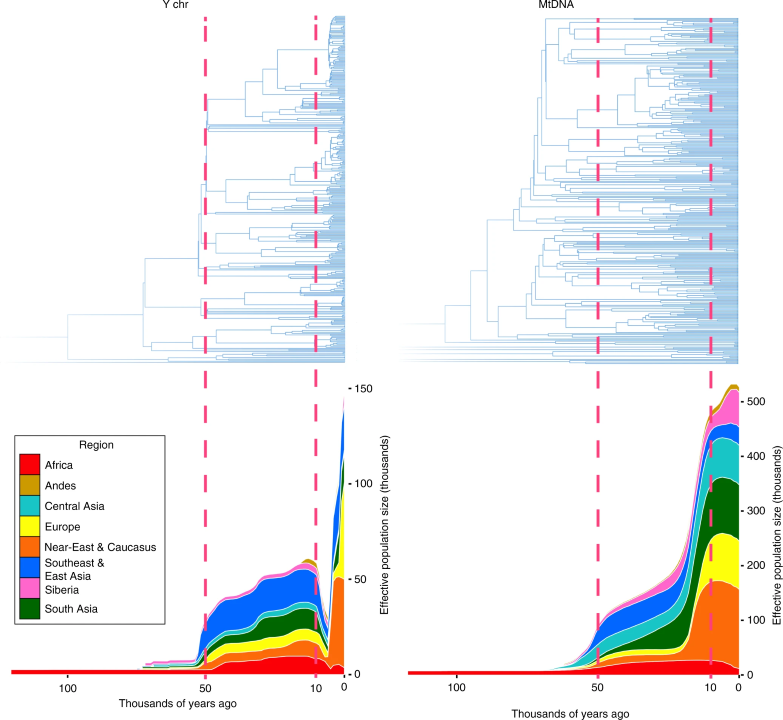

The article was centred around a study by Karmin et al. (2015) which after examining Y chromosomal & mitochondrial DNA sequences from 110 populations around the world discovered that a drastic reduction in the effective population of men had occurred in a period between 8 and 4 thousand years ago.

Here we see a visual representation of this bottleneck:

While the effective population size of men has been consistently lower than that of women, something strange seems to have happened around 10,000 thousand years ago which significantly accentuated this discrepancy. This would line up quite well with the Neolithic transition from hunter gathering to agriculture throughout the Old World.

So what caused this bottleneck? The manosphere’s explanation of choice is of course hypergamy and alpha dominated harems. The details are quite murky however, and often the fact that this extreme bottleneck was limited to the Neolithic era is omitted. For instance, this is what Myron from the Fresh & Fit podcast had to say on the matter:

Historically speaking, since the beginning of time, one man has procreated for every seventeen women. So what does that mean? That tells you that women were concentrating on a very small minority of men and a small minority of men were having sex with a majority of the women, because women are hypergamous by nature and pick the best guys.

To be fair, the general idea expressed here isn’t entirely controversial. It’s probably the most conventional explanation in fact. The authors of the study themselves hypothesized that “A change in social structures that increased male variance in offspring number may explain the results, especially if male reproductive success was at least partially culturally inherited”.

It could be the case that the resource accumulation and social stratification brought about by the agricultural revolution led to such extreme inequality that the wealthiest most powerful men were able to monopolize most of the women, who preferred to share such a man than settle for one of low status. This would give the appearance of a male population bottleneck despite relatively little change in the population.

It’s far from a settled question however, as there to my knowledge does not exist direct evidence for this scenario. It’s also not necessarily the case that we can simply extrapolate from surviving lineages to the mating dynamics of our ancient ancestors’ time. Phylogenetic reconstructions don’t directly tell us the ratio of men to women who managed to reproduce at a particular period in history, but rather the ratio of male to female lineages which survived to the present day. If a male lineage went extinct through genocide for instance, it’d leave no trace in our genome.

Is This A Plausible Explanation?

Just on its face, a ratio this extreme seems a little obscene, even if it is observed in some species like elephant seals. Is it really believable that prehistoric chads were hoarding nearly 20 women each while 95% of men simply accepted their fate as genetic dead-ends? That this system lasted for thousands of years without these hordes of beta men ever rising up against this rigged system which gave them no hope of fulfilling their primary biological imperative, but instead slaving away to maintain it? Do we really have such a low opinion of men?

Were children really better off in these arrangements when their father’s attention and resources were split between dozens of other children? Did this not create endless turmoil among all the jealous women vying for his attention too? Many such questions arise.

While we need more than personal incredulity to justify rejecting a hypothesis, it should inspire us to investigate the issue more deeply and attempt to find a more reasonable explanation.

Thankfully, Zeng et al. (2018) have already done most of the heavy lifting for us with a study titled ‘Cultural hitchhiking and competition between patrilineal kin groups explain the post-Neolithic Y-chromosome bottleneck’.

Before laying out their theory, they address other possible explanations.

First off, ecological or climatic factors such as stress or disease may impact male infant mortality and sex ratio at birth, they say, but they reject this as a substantial factor simply because its effects are marginal at best.

Secondly, Neolithic founder effects from small populations of male Neolithic pioneers could create the appearance of a bottleneck in modern Y-chromosomes, but they say that at least in West Eurasia this explanation fails because the population of Neolithic founding males was comparatively large (relative to the hunter gatherers they displaced), and greater diversity in mitochondrial lineages in modern populations wasn’t produced by retention of local hunter-gatherer maternal lineages. It also predicts the most intense bottleneck point just prior to the expansion of Neolithic pioneers and for it to be lifted after the expansion’s completion, but neither of these effects are observed.

Finally, they address the hypothesis proposed by Karmin et al. that an increase in intragroup social and material inequality caused an increase in male reproductive variance (as well as the transmission of such across generations).

They note that patrilineality could interact with social & material inequality to increase the heritability of male reproductive success along father-son genealogies. It also seems to be the case that polygyny is more common in agropastoral than hunter gatherer cultures, which would support the hypothesis.

On the other hand, they note several issues with the hypothesis. Firstly, the effect of social status on male reproductive success in hunter gatherers, agriculturalists and pastoralists are of similar magnitude (von Rueden & Jaeggi, 2016).

Secondly, not only is it intuitively hard to imagine, a reproductive ratio of 1:17 far exceeds that observed in the ethnographic records. They note how a skew this extreme is inconsistent with the social dynamics of anti-dominance coalitions in small-scale human groups (going back to my prior point).

Lastly, while it may be the case that long-term transmission of reproductive success could cause a steady accretion of reproductive advantage to certain patrilineages, inequality between men rose over time and certainly didn’t falter with the emergence of regional polities, chiefdoms, and states, which only amplified the concentration of wealth and power in societies.

Despite this, this is precisely when the Neolithic bottleneck is lifted, which flies in the face of the notion that material and social inequality was driving it through its influence on men’s reproductive variance.

Is There A More Plausible Explanation?

If we’re to rule out wide-scale polygamy resulting from greater variance in male mate value as a significant factor, what then is a more reasonable alternative?

They claim that intergroup competition between ‘patrilineal kin groups’ explains the bottleneck.

The general idea is that intertribal warfare would have caused a reduction in male genetic diversity as a consequence of these groups being organized around common paternal descent.

As hunter gatherers began to transition to agrarian societies, unilineal kin groups became the dominant form of social organization. The anthropological literature suggests a curvilinear trend whereby such groups are least common in societies which are among the lowest and highest levels of complexity (Blumberg & Winch, 1972). They were ubiquitously present however in societies with endemic warfare but without centralized authority (Ember et al., 1974). One reason why the transition to sedentary agrarian societies marked their emergence is that clear lines of succession were needed following the establishment of property.

The Y chromosome would be highly homogeneous within social groups, but heterogeneous between them. Competition would tend to occur between these groups, and in the event that one of them were eradicated, their genetic lineage would go with them.

The archeological record shows little evidence for warfare or violence in Upper Paleolithic Europe. In the Mesolithic era, it becomes scattered and episodic. About 500-1,000 years following the Neolithic transition however, warfare becomes widespread (Ferguson, 2013).

The transition likely created more incentive for initiating violence because as populations grew due to increased food production, there was a greater demand for additional land and resources.

Climate shocks affecting food security would have exacerbated this:

Nevertheless, some characteristics of Neolithic societies were already in place in the area and it can be assumed that people in this time and place competed over limited resources that were fixed in the landscape. This is generally considered as one of the main underlying reasons for initiating warfare in prehistoric times, especially if the survival of the community was perceived to be threatened, for example by serious climatic changes making subsistence unsettlingly unpredictable.

Meyer (2020)

Inevitably this would at times reach the level of genocide:

However, we can surmise according to ethnographic parallels that when serious disagreements arose in prehistoric times between independent groups, and all previous ‘diplomatic’ efforts had failed, the ultimate level of escalation was sometimes reached where one group might have considered the destruction of the opposing ‘others’ as the only feasible option for settling the ongoing conflict. Such a targeted annihilation of one group by another within a short period of time, might have been preserved in the bioarchaeological record as a massacre, which is the ‘most dramatic evidence of destruction’ available in prehistoric archaeology. Several examples of such massacres are indeed known from the Neolithic and even somewhat earlier periods.

Meyer (2020)

When it came to female tribe members, they would more often practice exogamy (marry between tribes), or would be ‘absorbed’ by conquering tribes, allowing female genetic diversity to be retained to a greater extent in the event that their original tribe were wiped out.

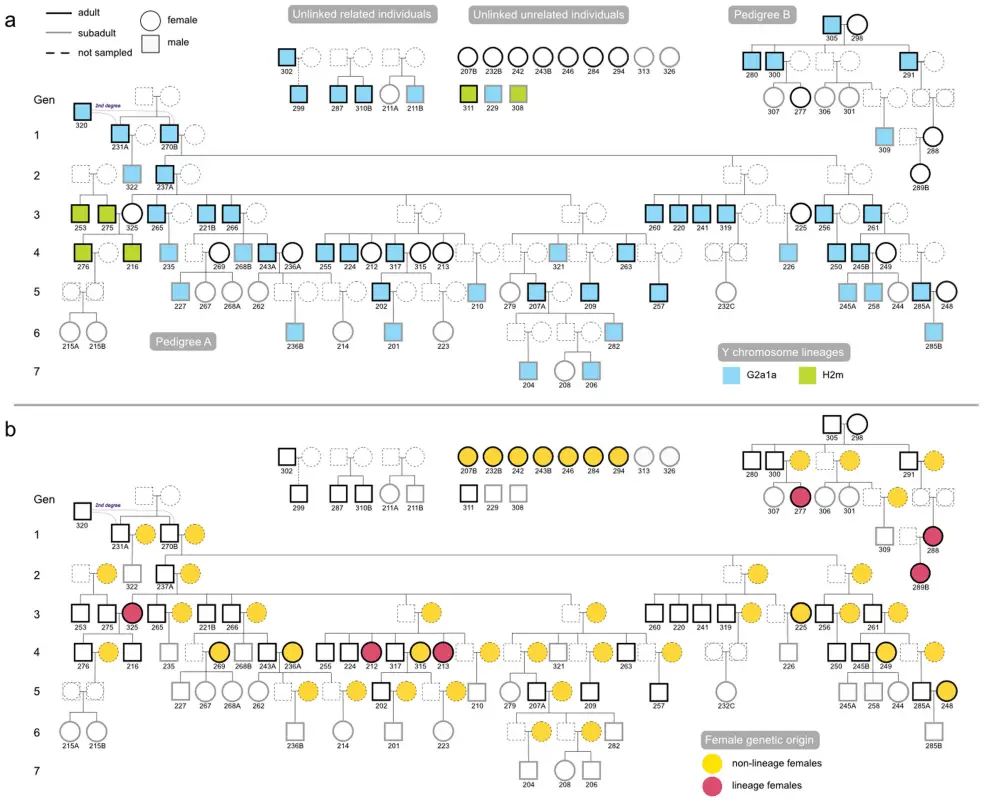

In support of this, Rivollat et al. (2023) discovered after analyzing ancient DNA from a French Neolithic burial site dated to 4,850-4,500 BC that across seven generations of the two main pedigrees, while they were linked almost exclusively by a common paternal ancestor, most of the women were of exogenous origin. Aside from two individuals, no mothers found had parents or ancestors buried at the site, and most of the women weren’t descendants of the main pedigrees.

They suggest that they were companions of male individuals from the main pedigrees:

No joint children were buried on site, nor could they be linked through other individuals to the pedigrees. Indeed, 17 adult male individuals have no children buried at the site, of which 13 are linked through their parents to either main pedigree. This general pattern points towards female exogamy and a virilocal residential system in which females in-migrated from their birthplace to their male reproductive partner’s residence.

They also found a distinct lack of half-siblings in the sample. This is a pretty direct indication that it’s unlikely that polygamy was indeed a common practice, at least in this community.

Returning to Zeng et al., they also add that since intergroup competition is associated with group size and potentially conflict initiation as well, there may have been positive returns to lineage size, accelerating genetic drift through the loss of minor lineages and spread of major ones.

This hypothesis also predicts that the bottleneck should start and end at the appropriate points in time:

Anthropologists have repeatedly noted that the political salience of unilineal descent groups is greatest in societies of ‘intermediate social scale’, which tend to be post-Neolithic small-scale societies that are acephalous, i.e. without hierarchical institutions. Corporate kin groups tend to be absent altogether among mobile hunter gatherers with few defensible resource sites or little property, or in societies utilizing relatively unoccupied and under-exploited resource landscapes. Once they emerge, complex societies, such as chiefdoms and states, tend to supervene the patrilineal kin group as the unit of intergroup competition, and while they may not eradicate them altogether as sub-polity-level social identities, warfare between such kin groups is suppressed very effectively.

As society grew larger and more complex, the relevance of these corporate kin groups waned:

Descent groups lose viability in complex state-organized, commercial-industrial societies because non-kin agencies of the state assume many kin functions (e.g., defense, education, welfare, adjudication). In complex societies, it is individuals (not families or larger kin groups) who take advantage of economic or occupational opportunities; when someone moves to a new job, parents and siblings are not likely to go along (and cousins and aunts and uncles even less likely).

Pasternak et al. (1996)

This allowed for an easing of the bottleneck, which again is exactly the opposite of what you’d expect under a ‘hyper-poly-gamy’ model, as male inequality would only get worse in these increasingly centralized and hierarchical societies.

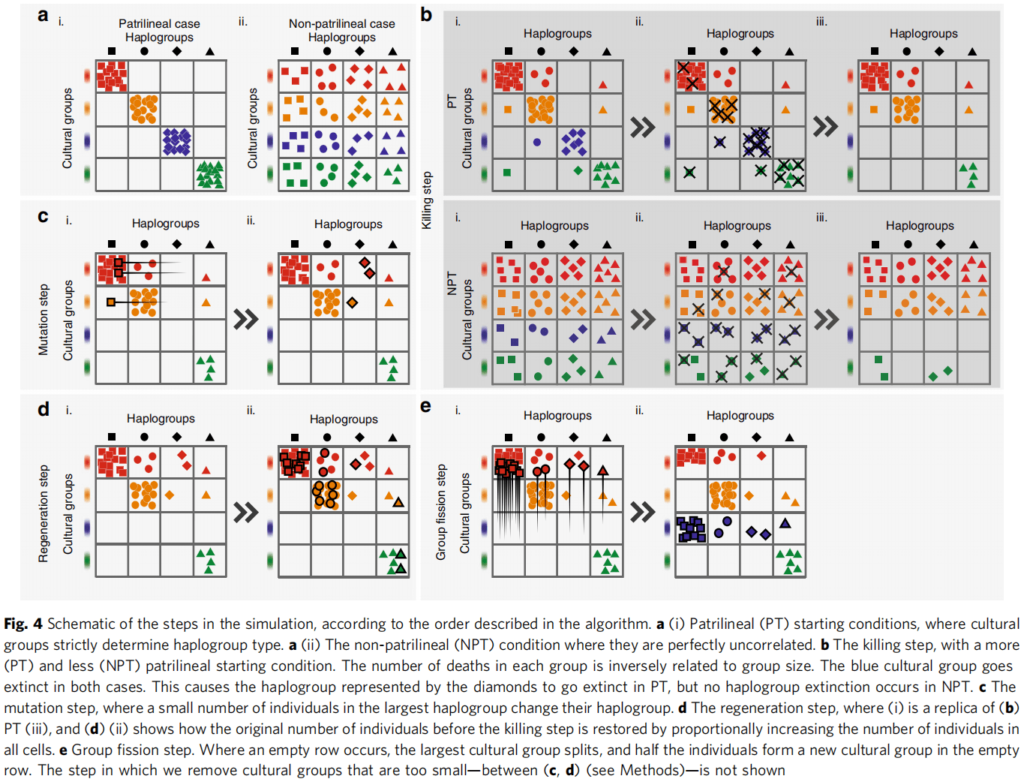

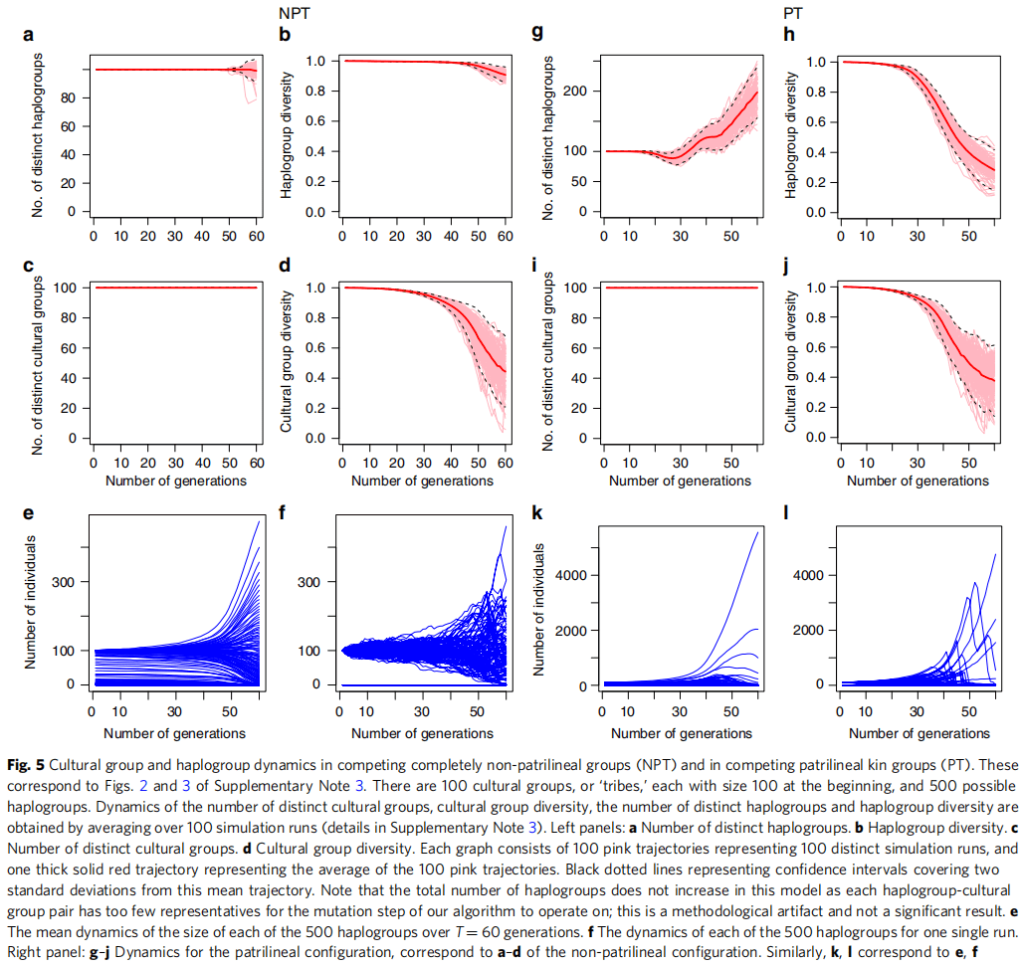

They tested their hypothesis using mathematical models:

As expected, in simulations involving patrilineality, we observe a bottleneck phenomenon in the Y chromosome in the absence of fluctuations in the male population size across generations, and one or several haplogroups eventually come to dominate. Additionally, “a rapid, sustained increase in the frequency of a particular Y-chromosomal haplogroup over a short timespan may cause rapid, proportional accumulation of mutations among carriers of that clade over that timespan, due simply to numerical and proportional advantage. This may match the conditions under which star-shaped ‘bursts’ appeared in the Y-chromosome genealogy of dominant clades among modern populations”.

Simulations without patrilineality didn’t exhibit these characteristics however:

Additional evidence they cite for their hypothesis includes observations of modern day Central Asians:

Central Asian pastoralists, who are organized into patriclans, have high levels of intergroup competition and demonstrate ethnolinguistic and population-genetic turnover down into the historical period. They also have a markedly lower diversity in Y-chromosomal lineages than nearby agriculturalists. In fact, Central Asians are the only population whose male effective population size has not recovered from the post-Neolithic bottleneck; it remains disproportionately reduced, compared to female estimates using mtDNA. Central Asians are also the only population to have star-shaped expansions of Y-chromosomes within the historical period, which may be due to competitive processes that led to the disproportionate political success of certain patrilineal clans.

Whales, which show an opposite pattern:

Analogous phenomena are also found among nonhuman species. In whales, species with matrilineal organization such as Orcas, Pilot and Sperm whales have reduced mitochondrial diversity. The reduction is such that cultural selection operating at the group level has been invoked to explain the phenomenon.

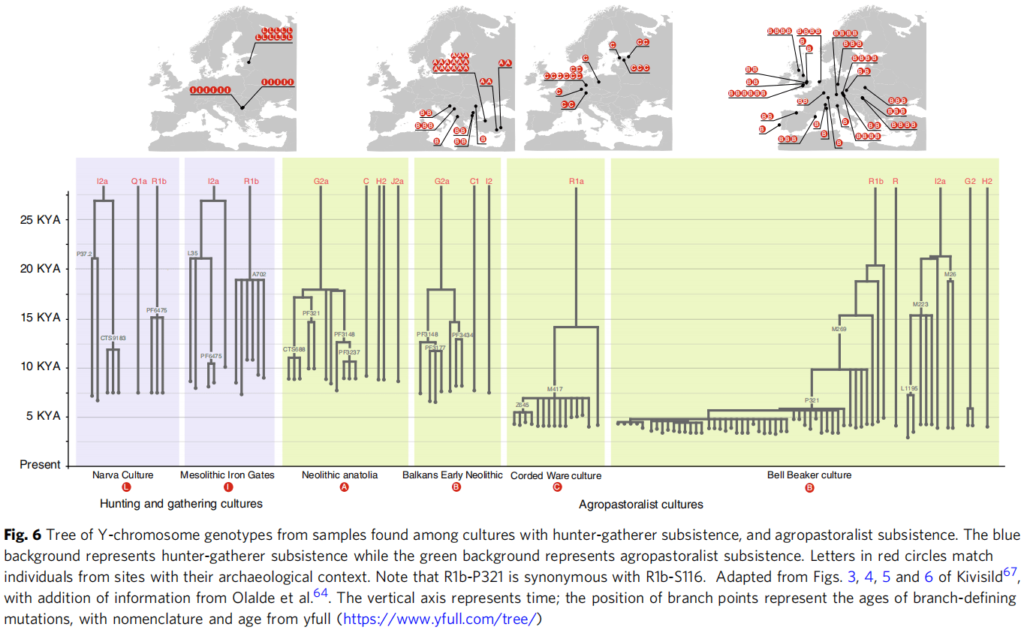

Phylogenies constructed from ancient DNA samples found across Europe from cultures with both hunter-gatherer and agropastoral modes of subsistence:

Which show that Y chromosomes from agropastoralist samples are more homogeneous and have more recent coalescences.

And also the surnames of Irish and English men:

Irish men sharing the same surname, even very common ones, are approximately 30 times more likely to share a Y-chromosomal haplotype than a random pair of Irish men. This is not the case for the English, who demonstrate much weaker signals of coancestry between Y-chromosomes and surnames, especially when the surname is very common. This difference parallels contrasts in the relative importance of patrilineal clans in the social origins of surnames in the history of the two populations

So it looks like the bottleneck may have been interpreted too hastily, and there turns out to be another cultural mechanism that better fits the data. It just required a more nuanced investigation.

What About Outside The Neolithic?

It still remains the case that male genetic diversity is markedly lower on each side of the Neolithic, even if to a lesser extent.

War could still be an effective explanation. While the homogenization of the Y chromosomal gene pool within groups would facilitate a more concentrated effect on male genetic diversity, we’d probably still expect to see a higher reduction in male than female genetic diversity over time simply due to more men being slaughtered, while women would often be captured as sex slaves and so on.

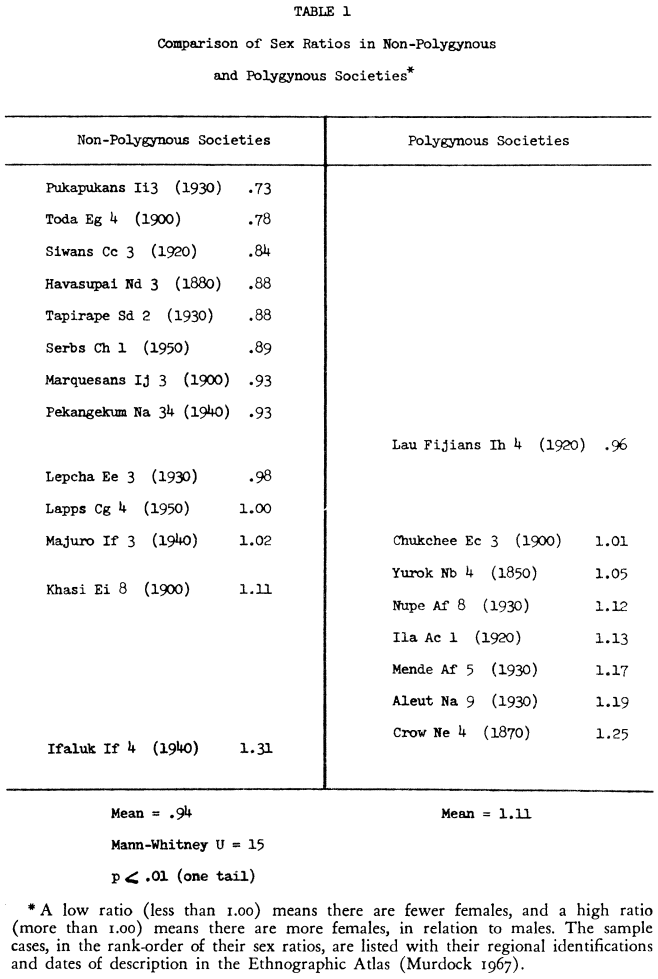

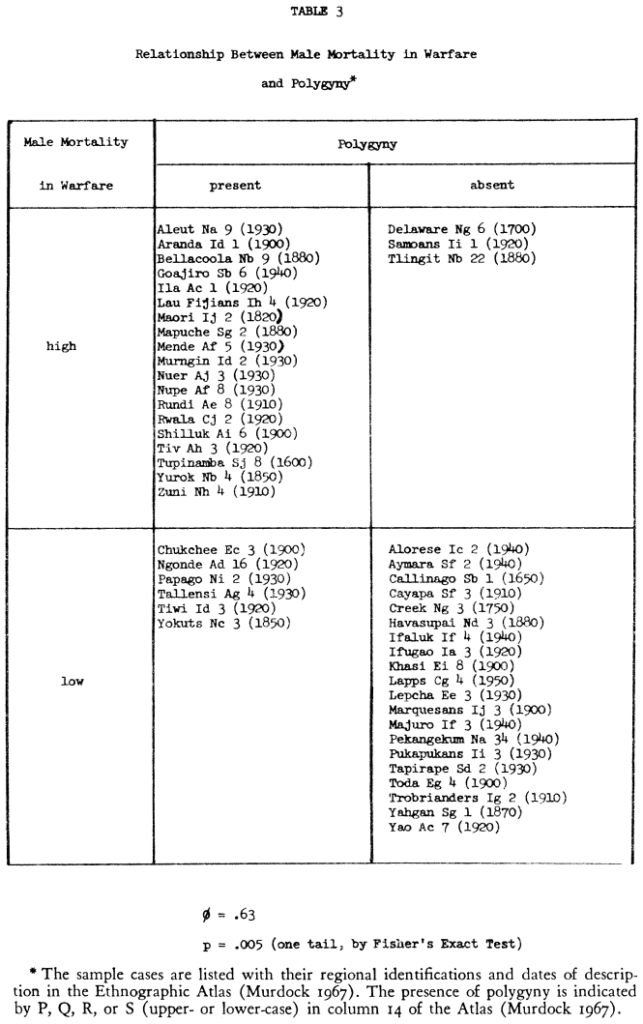

To the extent that polygamy was practiced, it likely would’ve largely been as a result of war leading to imbalanced sex ratios (Ember, 1974) and in turn women in need of provision. It also would’ve aided in replenishing the population.

Of course some people would argue that we have the causation here reversed, but a modern example of this phenomenon can be seen in the case of the Syrian civil war.

While the rate of polygamous marriages registered in the capital sat at 5% in 2010 before the war broke out, it had shot up to 30% by 2015:

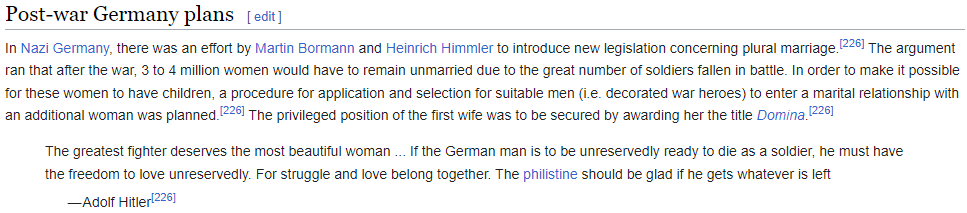

In another timeline, certain men were permitted to take additional wives in post-WW2 Germany to counteract the female surplus:

An intriguing possibility relating to natural selection was proposed by Sayres et al. (2014). Their models found that extreme sex-biased processes (e.g. mass polygamy) were alone insufficient to explain the lower diversity observed in the Y chromosome, and moreover models involving ‘purifying selection’, I will let them explain:

Purifying selection can reduce genetic variation at linked neutral sites via a process called background selection, which has received extensive theoretical treatment in the literature. Purifying selection has already been documented for the mtDNA. Due to the lack of homologous recombination throughout most of the Y chromosome, background selection is expected to have a particularly strong effect, severely reducing diversity on the Y chromosome. Two factors determine the overall effect of background selection on reducing neutral diversity in non-recombining regions: 1) The strength of selection, and 2) the number of sites subject to selection. At approximately 60 million base pairs, there are orders of magnitude more sites that may be subject to selection on the human Y chromosome than on the mtDNA. Selection may actually be quite weak on individual mutations that occur on the Y chromosome, but in the absence of recombination, if many sites are possible targets of this weak selection, this can lead to a strong reduction in diversity among Y chromosomes.

were consistent with it.

The apparent effect of hyper-poly-gamy may have also been amplified by the descendants of polygamous elites enjoying more privileged positions in society and thus their lineages having a higher chance of surviving to the present day than those of monogamous peasants.

Female Choice?

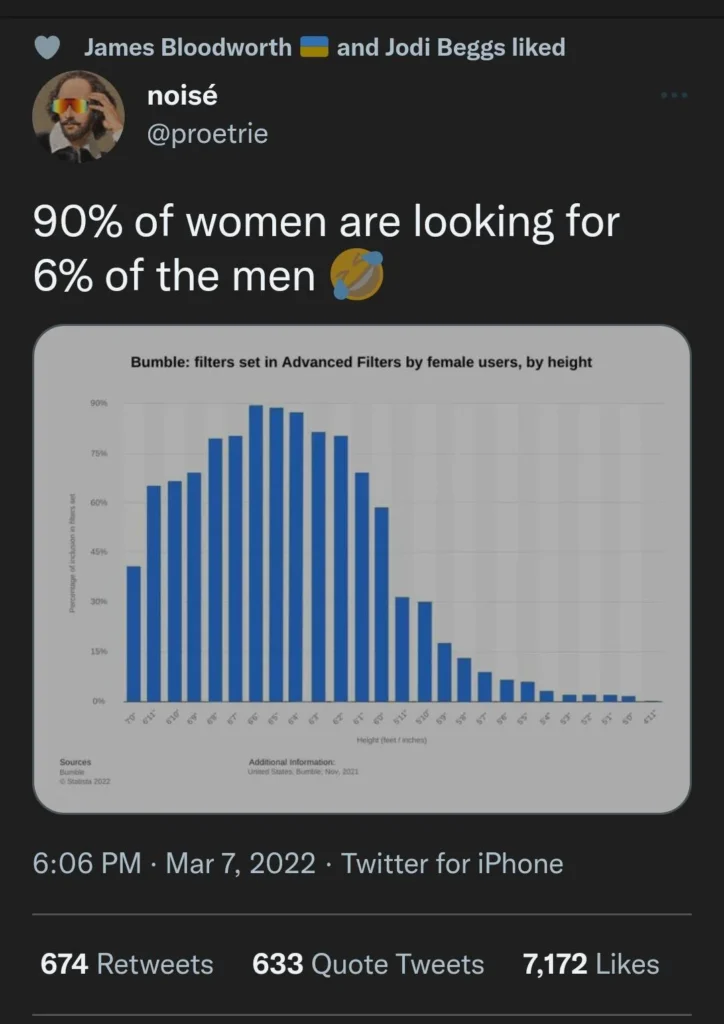

Another thing to consider is even assuming that it was the case that polygamy caused the bottleneck (and wasn’t practiced out of necessity due to a skewed gender ratio), was this necessarily driven by hypergamy?

If we ask women how they feel about polygamy, they don’t seem too fond of the idea. For instance, in a sample of 393 UK heterosexuals, Thomas et al. (2022) found that only 5% of women were open to polygyny as opposed to 39% of men.

Many Muslim women seem to be in favour of a ban on polygamy:

Around 91.7% or 4,320 women have spoken out against polygamy saying that a Muslim man should not be allowed to have another wife during the subsistence of the first marriage.

Hindustan Times

You can imagine the jealousy and catfights that’d ensue after a man suddenly decides to introduce a new wife into the picture.

A somewhat awkward fact is that polygamy is most prevalent in the most patriarchal societies rather than ones where women have the most self-determination, which doesn’t seem to jive well with the idea that monogamy is an institution that is imposed against the will of women who yearn to be the fourth wife of a high value male.

How about if we look at a famous harem owner like Genghis Khan, did his wives and concubines simply flock to him because he was a high value alpha male?

- The marriage between Börte and Genghis Khan (then known as Temüjin) was arranged by her father and Yesügei, Temüjin’s father, when she was 10 and he was 9 years old.

- At the recommendation of her sister Yesugen, Temüjin had his men track down and kidnap Yesui. When she was brought to Temüjin, he found her every bit as pleasing as promised and so he married her. The other wives, mothers, sisters and daughters of the Tatars had been parceled out and given to Mongol men.

- Khulan entered Mongol history when her father, the Merkit leader Dayir Usan, surrendered to Temüjin in the winter of 1203–04 and gave her to him.

- Möge Khatun was a concubine of Genghis Khan and she later became a wife of his son Ögedei Khan. The Persian historian Ata-Malik Juvayni records that Möge Khatun “was given to Chinggis Khan by a chief of the Bakrin tribe, and he loved her very much.”

- Ibaqa was the eldest daughter of the Kerait leader Jakha Gambhu, who allied with Genghis Khan to defeat the Naimans in 1204. As part of the alliance, Ibaqa was given to Genghis Khan as a wife.

- Daughter of Li Anquan of Western Xia, given to Genghis Khan in submission to Mongol rule during the campaign of Western Xia.

- Daughter of the Jurchen Jin emperor Wanyan Yongji married to Genghis Khan in exchange for relieving the Mongol siege upon Zhongdu (Beijing) in the Mongol conquest of the Jin dynasty.

On the contrary, most of them appear to have been handed to him in diplomatic negotiations or were taken by force.

Conclusion

Patrilineal kin groups provide a compelling cultural mechanism by which this bottleneck may have occurred, because enough violent conflict between them would eventually cause most Y DNA lineages to perish.

This would give the appearance of a male population bottleneck without an equivalent reduction in the effective population size, i.e. even if just as many men as women were reproducing at some point in the timeline, it would still seem like disproportionately more women were, simply because mtDNA clades were more widely distributed across different populations.

It also means we don’t have to come up with an ad hoc reason why even the highest polygamy rates in the world today don’t even begin to reach such extreme levels, and rarely exceed 15% or more than two wives in contemporary small-scale societies.

Of course, it’ll likely never be possible to truly prove what happened. We can only make inferences from scattered data points, and this kind of ambiguity allows room for people to shoehorn in their preferred narrative. At the end of the day it’s up to you to decide what’s most plausible in light the available evidence.

Whatever the case may be, what’s certain is that history has been a ruthless game of survival of the fittest.

References

Diep, F. (2015). “8,000 YEARS AGO, 17 WOMEN REPRODUCED FOR EVERY ONE MAN”. Pacific Standard. https://psmag.com/environment/17-to-1-reproductive-success

Karmin, M., Saag, L., Vicente, M., Wilson Sayres, M. A., Järve, M., Talas, U. G., Rootsi, S., Ilumäe, A. M., Mägi, R., Mitt, M., Pagani, L., Puurand, T., Faltyskova, Z., Clemente, F., Cardona, A., Metspalu, E., Sahakyan, H., Yunusbayev, B., Hudjashov, G., DeGiorgio, M., … Kivisild, T. (2015). A recent bottleneck of Y chromosome diversity coincides with a global change in culture. Genome research, 25(4), 459–466. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.186684.114

Zeng, T. C., Aw, A. J., & Feldman, M. W. (2018). Cultural hitchhiking and competition between patrilineal kin groups explain the post-Neolithic Y-chromosome bottleneck. Nature communications, 9(1), 2077. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-04375-6

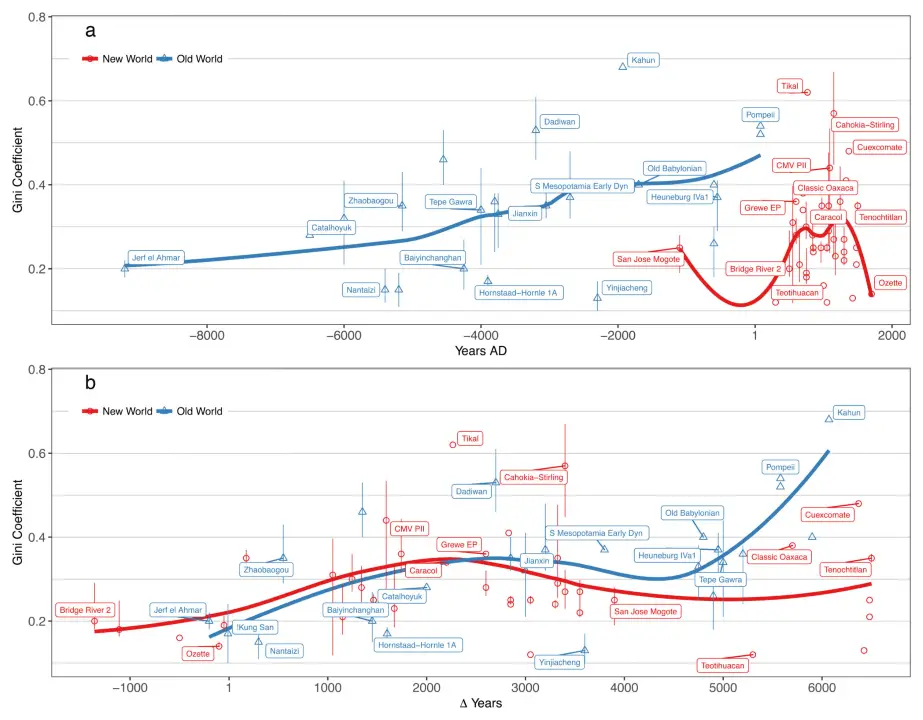

Kohler, T. A., Smith, M. E., Bogaard, A., Feinman, G. M., Peterson, C. E., Betzenhauser, A., Pailes, M., Stone, E. C., Marie Prentiss, A., Dennehy, T. J., Ellyson, L. J., Nicholas, L. M., Faulseit, R. K., Styring, A., Whitlam, J., Fochesato, M., Foor, T. A., & Bowles, S. (2017). Greater post-Neolithic wealth disparities in Eurasia than in North America and Mesoamerica. Nature, 551(7682), 619–622. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature24646

Blumberg, R. L., & Winch, R. F. (1972). Societal complexity and familial complexity: Evidence for the curvilinear hypothesis. American Journal of Sociology, 77(5), 898–920. https://doi.org/10.1086/225230

Ember, M. (1974). Warfare, sex ratio, and polygyny. Ethnology, 13(2), 197. https://doi.org/10.2307/3773112

The Cambridge World History of Violence. (2020). In Cambridge University Press eBooks. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316341247

Rivollat, M., Rohrlach, A. B., Ringbauer, H., Childebayeva, A., Mendisco, F., Barquera, R., Szolek, A., Le Roy, M., Colleran, H., Tuke, J., Aron, F., Pemonge, M. H., Späth, E., Télouk, P., Rey, L., Goude, G., Balter, V., Krause, J., Rottier, S., Deguilloux, M. F., … Haak, W. (2023). Extensive pedigrees reveal the social organization of a Neolithic community. Nature, 620(7974), 600–606. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06350-8

Pasternak, B., Ember, C. R., & Ember, M. (1996). Sex, Gender, and Kinship: A Cross-Cultural Perspective. https://openlibrary.org/books/OL1001747M/Sex_gender_and_kinship

Haddad, R. (2016). “Polygamy and divorce on the rise in war-torn Syria”. The Times of Israel. https://www.timesofisrael.com/polygamy-and-divorce-on-the-rise-in-war-torn-syria/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polygamy

Wilson Sayres, M. A., Lohmueller, K. E., & Nielsen, R. (2014). Natural selection reduced diversity on human y chromosomes. PLoS genetics, 10(1), e1004064. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1004064

Thomas, A. G., Harrison, S., Mogilski, J., Stewart-Williams, S., Dr, & Workman, L. (2022, July 6). Polygamous Interest in a Mononormative Nation: The Roles of Sex and Sociosexuality in Polygamous Interest in a Heterosexual Sample From the UK. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/27uaw

Hindustan Times (2017). “90% of Muslim women want ban on oral talaq, finds survey”. https://www.hindustantimes.com/india/90-of-muslim-women-want-ban-on-oral-talaq-finds-survey/story-KOqZCjWYx52D8ES1cSo7uI.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wives_of_Genghis_Khan

In chimps, females are exchanged between tribes as well.

They don’t show this genetic pattern.

I think an easier way to think about the explanation is that while one can think about it as about selection for patrilines, you can also the same pattern explained by varying reproductive success for men, but it is (likely) operating at the great-great-great-grandchild level (or similar), rather than at the level of the child (polygamy). I think it is unlikely that most patrilines would be coherent for more than 4-5 generations in such non-state context, so that is probably the maximum or so.

For women, you do not find this variation in number of great-great-great-grandchildren as women circulate patrilines.

The explanation does not have to be very violent either (though it also very much could be), it could just be that some patrilines live in regions that just happen to be more socio-ecologically successful.

many westerners haven’t experienced patrilineal clan life for decades. I legit came from a chinese patrilineal village the name of village is literally our patrilineal ancestors’ last name. Almost all male members have same last name. (except some male members married into women’s family but it’s rare normally because they don’t have sons or outsider clan who moved here) however last names of our female members are very plural. we have tradition to preserve our patrilineal family tree called jiapu(家谱)i checked mines, our ancestors rarely practice polygamy. TBH i wouldn’t surprise that mtdna is much more diverse than y dna in my village, because our matrilineal ancestors or relatives rarely stay in our village. In chinese traditional culture, there is a old saying, married off daughters are like water which thrown off. 嫁出去的女儿泼出去的水 they will never come back unless spring festival. This practice is not unique in china, it’s very common throughout human history until today. in china rural area, many chineses still practice ritual that worship patrilineal ancestors, these rituals usually exclude female members. unlike in english in chinese languages , we legit call maternal grandparents 外(outside)祖父母 maternal grandchildren 外(outside)孙子女 in english everyone knows they are not differentiated.

in chinese traditional confucius culture, daughters’ consent usually doesn’t matter, marriages are arranged by parents, sometimes sons’ consent doesn’t matter as well, but they can practice concubinage or visit prostitutes back then. confucius teachings taught wife shouldn’t be jealous that husband marries concubines, jealousy is considered demerit of wife that husband can divorce wife because of it. these jealous women are highly stigmatized by society back then. because they prevented their husbands from having more sons. and concubinages usually equated to slavery in ancient china, husband usually purchased them from other men or other slave masters. concubines had no rights compared to wives. In mongolian cultures, sources of concubines are usually war captives or their family sold them to a war winner in exchange of peace. han confucius intelletuals used to criticised how barbarian these mongols’ marriages. because they snatched other tribes’ daughters as wives without their fathers’ consent as wives or concubines(at least in confucius daughter’s parent’s consent is compulsory condition for marriage) and they had no moral issues to marry their fathers’ younger wives or concubines as wives or concubines. many westerners interpreter eastern cultures so wrong. they mistaken eastern polygamy culture for their mistresses culture(mistresses often are consented to mingle with nobelities .)

in Ancient china Chineses did practice female infancide often because of son preference, it’s not unique in china, greek and roman and other patrilineal emphasized son preference culture people also practiced. there was gender ratio skewed badly. Western missionary recorded this practice, and also recorded sodomy was rampant among chinese men back then because the gender ratio is skewed so bad ancient chinese incels?! couldn’t marry wives so they practiced homosexual unions (in Fujian it’s called 契兄弟 like contract brotherhood?) these sodomy practices were highly tolerated back then. western missionaries were upset about that, and said chinese people are degenerate should stop these practices. I think prevailence of homosexual relationship in greek-roman also because skew of gender ratio. i do noticed some research pointed out gender ratio was skewed in roman-greek cuased a lot of lonely male and age gap marriages.

Femchimp fucks many male chimps during mate season meanwhile women fuck around is very recent thing.

Hi i think that i saw you visited my web site thus i came to Return the favore I am attempting to find things to improve my web siteI suppose its ok to use some of your ideas

I do not even know how I ended up here but I thought this post was great I dont know who you are but definitely youre going to a famous blogger if you arent already Cheers

Hi my family member I want to say that this post is awesome nice written and come with approximately all significant infos I would like to peer extra posts like this

I just could not leave your web site before suggesting that I really enjoyed the standard information a person supply to your visitors Is gonna be again steadily in order to check up on new posts

Hello, its nice article on the topic of media print, we all know media

is a great source of facts.

I like the comprehensive information you provide in your blog. The topic is kinda complex but I’d have to say you nailed it! Look into my page Webemail24 for content about Bitcoin.